Adult Literacy

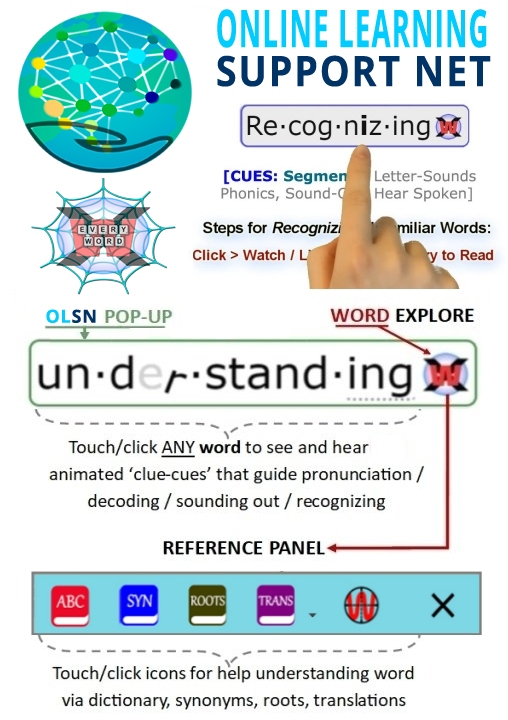

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Adult Literacy Statistics

David Boulton: How many people have literacy related difficulty in life? What kind of numbers are we talking about?

Robert Wedgeworth: Well, if we look worldwide, last year when the Director General of UNESCO made his annual statement on the occasion of International Literacy Day in September, he had some good news. The good news is for the first time in history over half of the women in the continent of Africa are literate. But that’s the only good news you can see in those worldwide statistics, because we’re still talking about almost a billion people in the world who either cannot read and write or have very low literacy skills.

In this country, the current estimates of the extent of adult low literacy are based primarily on the surveys that were taken in the early 1990’s. At that time we estimated that there were about ninety million adults with low literacy skills, about half of them at the lowest level that we would determine literacy skills. In our State of Literacy Report which we issued in November of 2003, we estimated that those numbers are likely to increase sharply, primarily due to the rates of the immigration, due to the rates of students who are dropping out or being pushed out of high school, due to the growth of the number of offenders in our system who are diagnosed with low literacy skills in state and federal prisons, and other factors as well.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#LiteracyStatistics

Literacy & Social Pathology

David Boulton: This plays right into the National Institute for Literacy’s upcoming report on the state of adult literacy and the strong correlations between the patterns that we see at the NAEP level and how they seem to play out in adult society. That high percentages of inmates in prison are people of color and people that can’t read, and similarly in welfare and health care. There’s such a strong correlation between literacy and all these other social pathologies.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: How aware you are of what’s going on in your society is correlated with it. How often you vote, whether you’re registered to vote – that’s connected to literacy. Whether you’re working, what level job you’re working in, your likelihood of getting employed – all those are connected. Not all low literacy people commit crime, but it does appear that the largest percentage of people who commit crime are of low literacy. Every social pathology appears to be related to literacy attainment. Every good that we distribute in our society seems to be related to it. Literacy is a great enabler.

Let’s be honest – a child who comes out of an impoverished background in terms of what his mother or father can provide materially – if that kid does well in learning literacy he is much more likely to live at a higher standard than his parents, he is much more likely to be able to participate in any number of social activities that his or her parents can’t participate in. But the deck is stacked against that kind of a child, and the statistics suggest that he or she will probably end up more like their parents in literacy attainment (and the outcomes that can buy).

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#LiteracySocialPathology

Real Cost is Lost Self-Esteem

I think the main thing to emphasize for anyone who has worked with a child or with an adult who has a reading problem, either who is low literate or is just struggling with reading, is that it is very apparent that it is the lost human potential, the lost self-esteem…that is the most poignant. And in the end it’s the most significant, because the loss in self-esteem is what leads to a whole host of social pathologies that are very difficult to look in the face. Crime, substance abuse, and the school drop out rate –any of those things – they are very difficult to face. And there is a line to be drawn between low literacy skills and those social pathologies.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#TheRealCostisLostSelfEsteem

Corroboration From Different Sectors of Society

Robert Wedgeworth: There are still too many people out there who do not believe that we have as many functionally illiterate adults in this country as we do.

David Boulton: Yes, there seems to be quite a number of people who believe that the reading crisis is being pumped up as part of covert strategy to commercialize education.

Robert Wedgeworth: Except for the fact that we’re getting too much corroboration coming back from different sectors of society.

David Boulton: Yes.

Robert Wedgeworth: From the health care industry, from the…

David Boulton: Prisons.

Robert Wedgeworth: The prisons — as I point out in that paper.

David Boulton: It’s the correlation of all of these things that gives credibility and strength to this underlying assessment of the adult low literacy population.

Robert Wedgeworth: Exactly. That’s right. Back in the 1970’s when the U.S. Department of Education first surfaced the issue, and even in the 1990’s when they did that first national assessment, people didn’t believe those figures. In our State of Literacy Report we predicted that the next survey would show that the numbers of adults with low literacy skills will increase significantly over what the previous survey showed in the early 1990’s. There were many skeptics about those statistics, but as you know, there’s been substantial corroboration of those statistics since then coming from different quarters, coming from the prison system with the number of offenders who have low literacy skills and coming from the health profession.

There are several other factors that will contribute to those numbers increasing in the next survey. One is that we’ve had an enormous growth in immigration to the United States. And we know, because we frequently see the stories of immigrants who come, they work hard, they put their children through school, and the next generation does well. But this, based on the statistics and our experience, is the exception rather than the rule. Many of these families take two and three generations before they can move into the mainstream of American life.

Another fast growing area for us is teenagers who are now being subjected to these mandated state exams, and they are having difficulty or either they’re having anxiety about their ability to pass the state exams. So, we’re getting enrollees in our programs using our materials to help prepare themselves for those mandated exams.

Though the numbers of students who are dropping out hasn’t changed, the overall numbers are increasing by the number of students who are being pushed out. There was a major story in our local newspaper recently about push-outs. But what they failed to indicate was why administrators would be interested in pushing someone out of school who is not doing well. The motivation is that under the accountability rules that are associated with No Child Left Behind schools are penalized for students who don’t do well and don’t advance. So that if they have students who have other issues in their lives, like becoming parents at an early age, they have to work at night or they attend school sporadically, they’re encouraged to push those students out of school so that they don’t drag down the numbers that relate to the rest of the student body.

So, there are a number of reasons why these statistics are likely to increase before they decrease. We really have to address the problem of adult literacy head-on.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#Misperceptions

Literacy and Civic Participation

Robert Wedgeworth: There are still too many people out there who do not believe that we have as many functionally illiterate adults in this country as we do.

David Boulton: Yes, there seems to be quite a number of people who believe that the reading crisis is being pumped up as part of covert strategy to commercialize education.

Robert Wedgeworth: Except for the fact that we’re getting too much corroboration coming back from different sectors of society.

David Boulton: Yes.

Robert Wedgeworth: From the health care industry, from the…

David Boulton: Prisons.

Robert Wedgeworth: The prisons — as I point out in that paper.

David Boulton: It’s the correlation of all of these things that gives credibility and strength to this underlying assessment of the adult low literacy population.

Robert Wedgeworth: Exactly. That’s right. Back in the 1970’s when the U.S. Department of Education first surfaced the issue, and even in the 1990’s when they did that first national assessment, people didn’t believe those figures. In our State of Literacy Report we predicted that the next survey would show that the numbers of adults with low literacy skills will increase significantly over what the previous survey showed in the early 1990’s. There were many skeptics about those statistics, but as you know, there’s been substantial corroboration of those statistics since then coming from different quarters, coming from the prison system with the number of offenders who have low literacy skills and coming from the health profession.

There are several other factors that will contribute to those numbers increasing in the next survey. One is that we’ve had an enormous growth in immigration to the United States. And we know, because we frequently see the stories of immigrants who come, they work hard, they put their children through school, and the next generation does well. But this, based on the statistics and our experience, is the exception rather than the rule. Many of these families take two and three generations before they can move into the mainstream of American life.

Another fast growing area for us is teenagers who are now being subjected to these mandated state exams, and they are having difficulty or either they’re having anxiety about their ability to pass the state exams. So, we’re getting enrollees in our programs using our materials to help prepare themselves for those mandated exams.

Though the numbers of students who are dropping out hasn’t changed, the overall numbers are increasing by the number of students who are being pushed out. There was a major story in our local newspaper recently about push-outs. But what they failed to indicate was why administrators would be interested in pushing someone out of school who is not doing well. The motivation is that under the accountability rules that are associated with No Child Left Behind schools are penalized for students who don’t do well and don’t advance. So that if they have students who have other issues in their lives, like becoming parents at an early age, they have to work at night or they attend school sporadically, they’re encouraged to push those students out of school so that they don’t drag down the numbers that relate to the rest of the student body.

So, there are a number of reasons why these statistics are likely to increase before they decrease. We really have to address the problem of adult literacy head-on.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#LiteracyCivicParticipation

2000 Florida Election & Reading Difficulty

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: One aspect of this that I had personal experience with was one of the newspapers asked me to analyze the votes in the 2000 Florida election. Obviously, media attention was directed to the hanging chads and the failure of the machines to record people’s votes. The thing that is interesting is that in Florida there are probably more counties that are using paper ballots than machine ballots. One of the newspapers said let’s look at the paper ballots and see how we did there. Florida lost even more votes with paper ballots than machine ballots, and they lost these votes primarily because people couldn’t make sense of the directions.

Florida lost lots of votes because many citizens couldn’t do the simple reading tasks on the ballot. They would spoil their vote by voting multiple times for different candidates. Even this basic franchise of whether you get to cast a vote is connected to literacy. You’re less likely to go and try to vote, but if you do try, you’re more likely to fail and your vote will be lost. We’re almost fifty years beyond the Supreme Court saying there wouldn’t be any kind of a literacy bar to vote in this country.

David Boulton: Of course there’s going to be. Even if you get around the instrumental simple part of it, you’ve got the deeper issue of whether somebody is a competent participant.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#2000FloridaElection

The Role of Adults in Assisting Children who are Learning to Read

The next point I will make with you is a little different, because here again it comes out of our experience as an adult literacy organization; and that is, we underestimate the role that adults play in assisting children to learn how to read. In most cases when we think about that we think about adults helping children with their homework, helping them with their reading material. But children learn lots of things from adults that improve their ability to read and understand the world that doesn’t come out of books.

There are many, many examples. When a child grows up in a home where they never see someone write a check, they never see someone reading a newspaper; unlike me, their fathers don’t sit down and teach them how to calculate batting averages so they can read the sporting page. Those are the kinds of things that are incredibly important.

Now, if you take this country alone, when we look at what we’re doing in trying to put the emphasis on teaching children to read, in most of the families these things can be successfully reinforced by the parents or the other adults around the children. But you have a fairly substantial number of adults and parents who are incapable of giving that kind of reinforcement to their children.

And we know for a fact that a child who grows up in a home where the parents are functionally illiterate has about a fifty percent risk of becoming a functionally illiterate adult himself or herself. But that fact really hasn’t come through strong enough to get people to understand how important it is for us to attack adult literacy as a lever for being more successful with children’s literacy problems.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#TheRoleofAdults

Adult Literacy

Robert Wedgeworth: Well, we’ve traditionally been an adult literacy agency. There are many organizations around the world, including the public schools and private schools that focus their efforts on teaching children to read. There are not very many who focus on teaching adults to read. Yet we know from our experience that many children go through the school system and never quite get it. We forget from time to time that reading is a difficult skill to acquire, but it’s even more difficult to maintain and improve.

David Boulton: One of the things that we’re doing is looking at the top reasons or challenges that impede or make it difficult for people to learn to read. Clearly, the kind of home language environment they grow up in is a major, if not the biggest, factor. When you talk about helping children, ultimately, if you run through all of the list of things that made it difficult for them or add to the burden of the implicit challenge of learning to read the code, it’s the environment they’re coming out of and whether the environment has sufficiently rich oral language, and whether or not the people in it are reading sufficiently to have the vocabulary that comes with reading, and to expose children to reading behaviors. So, your work with adults is a direct line to helping the children, too.

Robert Wedgeworth: Yes. We frequently are asked why do we focus on adults. We think adults are the key to literacy as a whole, not only as a whole, not only for themselves but for children as well. Children learn much of what they know from the adults in their lives. Clearly, learning how to read comprised of two basic parts. First you have to learn how to decode. In many cases, children have difficulty with that first step of trying to put together unique sounds with the combination of letters that make those sounds on the printed page. Many adults find when they are having trouble with their reading that this was a step that they didn’t quite master when they were children. They just can’t quite grasp the relationship between o-u, or t-h, and the sound that they’re supposed to make when they read that on the page.

But that’s only half of it. We know that good readers only become good readers by constant practice. So, it’s not enough just to teach someone to decode, because many of our adult learners learn how to read at one time or another, but either were not encouraged to read or didn’t pick up the reading habit, and therefore they never continued to improve building their vocabulary.

We know from extensive testing some of the research on children that shows us today that a child of even average ability, if they learn how to read, and they continue to develop this practice, enlarging the vocabulary that helps them understand and explain the world around them, can function almost as well as children with superior intellectual abilities. So it is really a key.

But above and beyond that, we also know that children who come from homes where the parents have low literacy skills have about a fifty-percent chance of being low literate adults themselves. So certainly that environment at home — it’s not necessarily the parents, it could be whoever is the principal caregiver, aunts, uncles, grandparents, who contribute to the learning of that child.

That’s the reason we see that focusing on adults gives you multiple beneficiaries. Our adults in our program are very good at encouraging their children to learn how to read and to stay in school. They stay in school far longer than the children of adult learners who are not enrolled in some kind of adult education program. So, our focus on adults has multiple beneficiaries, and we think it’s the key to any total literacy program. There is no literacy program we’re aware of that can have the kind of success that we would like without a parental component to it, or an adult component to it.

Our current program in the U.S. says “Leave no child behind.” We would say, “Leave no adult behind, and that will help us leave no child behind.”

David Boulton: Let’s leave no one behind.

Robert Wedgeworth: So, in effect, we’re leaving no one behind. There’s a common tendency for societies to write off a current generation with respect to a given problem and focus their attention on the next generation. Unfortunately, we have adults who have low literacy skills in virtually every generation, for various reasons. Partly because of learning disabilities, partly because of not learning how to decode, partly because they never gained the reading habit, didn’t have to use it as much as they might have in other kinds of occupations. So, we know that in every generation people fall out. Our effort is to try to see that we don’t leave anyone behind.

I think the most important point that we would make is that adult learners don’t come to us just with difficulties in reading and writing. Our learners represent some of the poorest people in our society. They have multiple issues in their lives. Many of them have long term illnesses that have prevented them from holding even the most menial job, if it involves physical labor. Many of them have other kinds of problems, they are ex-offenders or they’ve had problems with substance abuse. These are issues that they bring with them to their adult learning. And here again, as in our international program, they’re using our literacy programs to help them change the circumstances of our life.

The reason that I mention this is because everyone’s heartstrings are tugged by a child learning how to read. And in many cases, their hearts are hardened by the circumstances of the lives of adult learners. But they don’t understand that every adult learner has a relationship with a child. It may not be their own child, it may be a niece or a nephew. To the extent that they can contribute to encouraging that child to stay in school, to learn to read and write, that they can contribute that from their own learning, then we’re well ahead of the game. Even the child of the worst offender deserves to learn how to read and write and make their own way in our society.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#AdultLiteracy

Children's Futures all but Fated by Reading

David Boulton: What we’re getting as we start to explore the facets of this is that it seems as if our children’s futures are all but fated, not fated, but all but fated by how well they learn to read.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, that’s true. Particularly if we go back to the bookend analogy. Those children who are the caboose on the train, at the bookend on the left side of the books, are children who are at substantial academic risk.

Children who are failing at reading at the end of the first grade are extremely likely to be failing at reading at the end of fourth grade. And failure in reading strongly predicts failure in all other academic subjects. So, a child who is not breaking the code well, who has not figured it out, who is falling behind, is a child whose academic life course is at risk and because of that whose life is at risk because the economic opportunities of life.

Again, at the lower end of the dimension are ones that have profound effects on not only obvious things: quality of life dimensions, how much money one earns, or the neighborhood one lives in, but actually have effects on longevity, on how long you will live.

So, reading again, is absolutely fundamental. It’s almost trite to say that. But in our society, as it is structured, the inability to be fluent is to consign children to failure in school and to consign adults to the lowest strata of job and life opportunities.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Director, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#allbutFated

Shame Inhibits Getting Help

The major challenge that adult literacy programs have had traditionally is, first of all, identifying those persons who can benefit from our services. Since adult learners go to such a great extent to hide their embarrassment about having low literacy skills, it is really difficult to reach them. This is one of the areas in which we are having to put more funds into research, put more funds into determining what kinds of messages we can get out to society that can release the kinds of embarrassment that our people show.

Because when they get to our program, that’s easy, because adults, no matter how poor their literacy skills are, have a story. Every adult has a story. We always encourage them to tell us their story, to get them to relax and understand they’re in a place where they can be helped. The challenge, as I said before, though, is how to identify them and encourage them to come to us in the first place. I must admit that we haven’t really found an effective way to deal with this, but we’re working on it.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#ShameInhibitsGettingHelp

Low Literacy, Isolation & Shame

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: It is a kind of shame and they do hideout. Again, you see that participation in professional organizations and honorary societies are more linked to high literacy than low literacy. Well, that’s not surprising to anybody. But then you start to look and you see that adults who are low literacy are less likely to participate in athletic organizations. They’re less likely to participate in religious organizations. They don’t take part in as many of the social activities. They essentially get isolated.

You talked about it being an intellectual aversion, I think that’s part of it, but I think it’s even bigger than that. I think there’s a kind of a pulling back, there’s an embarrassment.

David Boulton: A shame aversion to everything that can stir up the kind of shame they want to avoid.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: You got it. It plays out in terms of I’m not going to participate in an intellectual discussion or debate, or whatever, but I’m also not going to participate in a lot of other social activities as well. So, they really are losing out on big chunks of their lives.

What it means is that we’ve put through the Civil Rights laws of the 1960s and we’ve done so many things to try to facilitate full participation, but literacy still is there as a barrier holding people out, even though politically the barriers have been taken down.

David Boulton: In a recent report from ProLiteracy, according to their surveys and also by American Medical Association research, they find that most of the people that can’t read go to inordinate lengths to hide it. Something like sixty percent haven’t told their spouses. One projection was that when low literate Americans walk into a grocery store or department store they are stirred with anxiety trying to make sure that they can get past the cash register without making a mistake that they can’t afford but that they can’t know they’ve made because they don’t have the skills.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: This hiding of the problem is real common. I don’t have a lot of statistics on it, but I have many personal experiences. For example, the mother who had come into one of our literacy programs – her kids were eight or nine and she was taking literacy classes because she didn’t want to hide it anymore. Her children, even at their age, didn’t know she didn’t have literacy. It was really surprising that she could hide that from them living in that household for so long. She said she always had to be on guard.

For example, she told us that, ‘When the kids come home from school I always make sure I’m busy – I’m washing, I’m ironing, I’m doing something so that if they come in and say here’s a letter from my teacher it allows me to say set it down I’ll get to it later, I don’t have time for that right now.’ She would depend upon her husband to do her reading.

In North Carolina we held a seminar on literacy for some teachers and we brought in a local business man who was low in literacy and he was willing to come in and talk to the teachers. The thing that was important was only two people in his life knew about his literacy problem: his wife and his business partner. Nobody else knew because he feared that if any of potential clients knew of the problem, he wouldn’t get contracts. He wanted this kept absolutely secret. We literally had to smuggle him onto the campus where we were working and put him in a room where we pulled the shades and had a guard at the door. (see Shame Stories)

These fears, sometimes it’s just a personal thing, that I don’t want my children to think less of me, and in other cases it really has larger meaning in terms of I don’t want to be discriminated against.

Robert Wedgeworth, President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#ShameInhibitsGettingHelp

Low Literacy Civic Participation & Health

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: One interesting analysis done with adults who are low in literacy is that low literacy individuals are less likely to read a newspaper than a high literate person. But, of course, these folks could still participate by getting information from television and have radio. There’s absolutely no reason why a low literacy person wouldn’t be able to access a lot of the information that is available over those media.

Except it turns out that lack of literacy has an isolating effect. What happens is low literacy people are less likely to watch informational shows on television, they’re less likely to watch news, for example, than other kinds of television.

David Boulton: How can they navigate?

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Exactly. They just don’t pay attention to stuff like that which means, they miss out on information about the candidates and elections and so on, but they also miss out on the large amount of health information that is on television news and so on. They don’t find out about the free pap smears down at the clinic. They don’t find out about the new statistics on smoking. They don’t find out about how to take care of their children better. And so their kids are at greater risk in all kinds of ways and they themselves are at greater risk.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#LowLiteracyCivicParticipationHealth

Shame Avoidance & Dependence

David Boulton: Sometimes it’s so powerful and fast and operating before those kind of rational reasons to just be an avoidance. One of the dimensions that we’re trying to bring to this is our work with emotional scientists and cognitive scientists and neuroscientists and bringing together just what is going on here. There’s no question human beings generally do not like to feel shame. We learn very young to become escape artists.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely.

David Boulton: We’re being put into circumstances, with this learning to read challenge, in which day after day, week after week, month after month, in some cases year after year, we’re forced to do something we’re not good at. It’s not like basketball or sewing or music or other things that are an option –you can’t avoid it. Andthese kids are developing a shame aversion to the feel of their own learning.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely. And when they become adults it ends up becoming a part of the social reality of their lives. It’s not just harder to learn then, but emotionally that whole network that builds up around you makes it tougher. So, if you’re that low on literacy what usually happens is you have to find somebody you can depend on. I might not want the whole world to know, but maybe my spouse knows that I am illiterate or maybe it’s one of my older kids, but nobody else does. What that does is it builds a dependency. If I were especially low on literacy and my wife knew it she would do certain things for me to take care of me and make sure that I’m okay. But what happens to the relationship when I decide this is terrible, I have to go learn literacy, I’m going to go enroll at the local library program or whatever. How much does that threaten the partner who has come to depend on my dependence?

Quite often when an adult who is really low on literacy goes off and becomes literate it leads to divorce. There are many cases documented where women are beaten or abused in various ways, either verbally or physically, certainly emotionally, because the partner who is depended on doesn’t want to give that up. The reason you’re going for literacy classes is because you want to get away from me.

Even when it’s a child who is the one who is being depended upon, the children get quite angry. It’s like mom wants to leave me or mom doesn’t love me anymore and that’s why she’s doing this. The trick is to catch this thing early enough so we don’t get to that point where there are those kinds of problems in people’s lives. That is essential.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#ShameAvoidanceDependence

International Scope

One thing we haven’t touched on and it’s a problem, if you’re talking about reading in the United States of America it’s not important to touch on, but if you’re talking about reading in the rest of the world it is. And that’s the question of access to instruction for reading and motivation to obtain access. There’s a billion people in the world living below any reasonable definition of the poverty level, large numbers of children are not learning to read simply because they don’t have the opportunity to be exposed to even poor reading instruction. Even when those opportunities exist there are many oral societies in which it is not at all clear to the adults in that society what is to be gained from reading. So, as we’re thinking in a world context, instead of the context of industrialized advanced nations, we also need to pay attention to access and motivation for literacy both in terms for children as well as adults.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Director, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#InternationalScope

Defining Learning

I think when you talk to people in the field of learning disabilities and ask about learning, you quickly start zeroing in on processing. How does information processing impact learning as a very, very key component of the learning process? For kids and adults with learning disabilities that’s where the chief problem is – how the brain either does or does not process information. How the brain sometimes very inefficiently retrieves information, stores information, processes it and expresses it. So, any theory of learning for us is very practical. How do people make sense, especially sense of language, and of other kinds of information that the brain has to work with?

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#DefiningLearning

Slow Readers Need More Time

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: I don’t know if you want to get into it or not, because it’s probably a little different than what your primary focus is on, but a very important thing is children grow up to be adolescents and young adults, and they need to — whatever they want to aspire to be, a teacher, a doctor, a lawyer, a writer, they often have to take a series of tests. One of the things we know is that because children who struggle to read don’t develop that left word forming area that’s responsible for being able to read more fluently, they read very slowly and require extra time.

That becomes a really important thing, because so many children who’ve worked so hard all their lives, they come to the point where they need to take an SAT or an ALSED Law School Admissions Test or a GRE, and they require extra time if they’re going to be able to show what they know. There’s been a very strong — it’s not a movement, I don’t know the right word — but these children are more and more being denied the extra time that they require.

David Boulton: There’s this general failure in the way that we think about assessment, to actually meet the kids in some way that reflects what their situation is.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s right, not to feel that they’re somehow getting away with something, or weak. If somebody needs glasses, you wouldn’t question it, or if a diabetic needs insulin, in the same we know that children, or young adults and adults who have reading problems require extra time. For me, as a physician and as a scientist, one of the most exciting things has been that we’ve been able to now demonstrate that in children who are dyslexic, they don’t develop that word forming area, but they do develop compensatory regions, on the right side of the brain and also in the front, that allow them to read, but not automatically so that they can become highly accurate readers, but by the investment of an extraordinary amount of time and energy. They can get there, but their route is much slower and more inefficient.

David Boulton: Right. There’s some kind of a circuit detour that’s had to happen for them.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Exactly.

David Boulton: Which is slower in processing and results in them needing more time to be as effective in the task.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Right. What I say now is that dyslexia simply robs a person of time, accommodations like extra time return part of it, and that a person who is dyslexic has as much a physiologic need for extra time as a diabetic needs for insulin.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Now that we can show that with our brain imaging, that’s made an extraordinary difference. Because I’ve seen too many young people who were applying to graduate school or professional school who struggled their lives to reach the point where they can read accurately, but not automatically, are turned down for extra time. It’s like somebody climbing to the top of a mountain and you suddenly step on their fingers, and don’t let them take that last step, and knock them down. So, it may not sound like an important thing to you, but for all those people who have had difficulty reading it is.

David Boulton: All of these dimensions are critical. We’re looking at the family context, the social context, very particularly at the emotional affective context as well as the cognitive processing challenge.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s at the very — that’s at the heart.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s the heart and soul of it. Because you can teach a person to read, and you can do all the things, but if they’ve had that hurt and that pain and that blow to their self-esteem, that’s the most difficult. We have no medicine for that.

David Boulton: Yes. And it’s not just a bad feeling they’re having; it’s fundamentally processing-level debilitating, draining of the efficiency that’s necessary to process the thing that could make them feel better. It works in a downward spiral.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s right.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University, Author of Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#SlowReaders

The Processes of Skilled Reading

Dr. Keith Rayner: Most of my own research is with skilled readers. So I’m interested in: What is it that people do when they’re skilled readers? What are the processes that they engage in?

I largely approach it by recording their eye movements while they read, and then try to infer what the mental processes are. We also do things where we make changes in the text, contingent on the eye movements. So, the classic experiment is one where we control how much you can see on each eye fixation via what’s called the “moving window technique.” Or we have also used another technique called the “boundary technique,” where you’re reading along, and there’s a word off to the right of where your eye is, but then when your eye goes into motion that word changes to another word.

David Boulton: So, you say you’re introducing a confusing or ambiguous situation and seeing what to do with it?

Dr. Keith Rayner: Well, it isn’t ambiguous. What we do is vary the relationship between the first word and the second word, so they can be semantically, phonologically or orthographically related. Then we try to infer what kind of information you would be getting from that word before you got to it, as a function of the relationship between the first and second word, and how long you then look at the word that’s there when your eyes get there.

We’ve done a little of this with children, but it’s mostly done with adults to try and see how much information you’re getting different distances from where your eye is currently looking at the moment.

Then the other thing I do a lot of is have people read sentences or text that do indeed have ambiguities in them, so there would be phonological ambiguity or lexical ambiguities or syntactic ambiguities. So they might read a sentence like, “While Mary was mending, the socks fell off her lap.” And there may or may not be a comma after mending, but if there’s not a comma after was mending, then usually people misplace the sentence because they take the sock to be the object that the verb was mending, and then they’re all messed up. So we try and infer what kind of structures are they building as they read to help them parse the sentence.

Or in the case of lexical ambiguity, they might read a sentence where the word bank is there, and then it turns out that it’s referring to a river bank, rather than a money bank. And so again, we try and see — infer what kind of processes they are using to understand by looking at what their eyes do.

David Boulton: Do you also put multiple tasks in to see whether they stack up to consume more time between fixations?

Dr. Keith Rayner: Well, in fact, there are fixation time differences as a function of these manipulations that we make. The task, for us, is typically always just read the text. Then there are variations in how long people look at things, as a function of these kinds of manipulations that we make.

Keith Rayner, Distinguished Professor, Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts; Director of the University’s

Eyetracking Laboratory. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/rayner.htm#SkilledReading

Word Recognition Timing Thresholds in Skilled Readers

Dr. Keith Rayner: What I know for adults, which is where all of our work is done, is that it takes about fifty milliseconds to get the information into the system. We’ve done experiments where people are reading, and if we mask the text or we take it away, but they get to see it for fifty milliseconds, that’s enough time.

David Boulton: So, by controlling how long something appears, you can find out what the recognition threshold is?

Dr. Keith Rayner: We can get the threshold for: How long does this stuff have to be there to get it into the system? If we leave it up for less than fifty milliseconds then reading falls apart; it’s really disrupted. But if we give them fifty or sixty milliseconds to see the text, then the orthographic information that’s there in front of their eyes gets into the system. It doesn’t matter if the text goes away after that. In fact, there are interesting things like if they’re looking at a low frequency word — so when you read normally, right, and we record your eye movements, you’ll always look longer at a low frequency word than a high frequency word. Even when we take the text away or mask it so it’s not there anymore, the eyes will stay in place longer for the low frequency word than the high frequency word, which is pretty interesting. So, that’s basically saying the mental operations that are involved in figuring out what that word is are driving the eye movements through the text.

David Boulton: So, there’s a loop going on that the eyes are a part of, being directed by, freed up, told to move on, at each iteration of some kind of coherent capture of object.

Dr. Keith Rayner: Yes. We’ve done other experiments where we present — do you know what the word “prime” means?

David Boulton: In the sense that it’s cuing up the — priming you for what’s coming next; it’s creating a decreased field of possibility around what’s coming?

Dr. Keith Rayner: Yes. So, imagine this scenario: You’re reading a sentence, and think of a target word in the sentence somewhere, say it’s the fifth word in the sentence. Before your eyes get to it, there’s just a string of random letters there. So we’re using this technique where we’re going to change things contingent on when your eye moves to that word. We make this change always during a saccade, during the eye movements, so that vision is expressed, you never see this change take place.

David Boulton: A saccade is a…

Dr. Keith Rayner: Saccade is a fancy name for eye movement.

David Boulton: Okay. So, when the eye is in motion is when you create this change so that you don’t actually get an attention blip when you’re on a more static eye fixation.

Dr. Keith Rayner: Right. The change takes place during saccade, you don’t see it. So in our standard boundary paradigm, that’s what would happen, we’d present a string of letters; or we’d present a word and you’d move into the word, and as soon as your eye starts approaching — you know, coming into a word, it changes to another word.

Now, then in a slightly different variation of that, we present a string of random letters where the fifth word should be. Your eye moves into that location. Now we present a prime word, which only stays on the screen for the first thirty or forty milliseconds of the eye fixation, and then it changes to the word that’s going to be there the rest of the time. Now, this change will get seen, because it’s happening during a fixation. There are two changes in this particular paradigm. What we do in those experiments is we vary the orthographic phonological or semantic relationship between the prime word and the target word.

David Boulton: So, you’re actually wanting to see how they recover from their own prediction?

Dr. Keith Rayner: Well, it’s not necessarily their prediction. It’s how much use they’re able to get in that early time frame of something that’s orthographically similar or phonologically similar or semantically similar to the target word.

David Boulton: Okay.

Keith Rayner, Distinguished Professor, Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts; Director of the University’s Eyetracking Laboratory. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/rayner.htm#TimingThresholdsinSkilledReaders

The Milliseconds Between Orthography and Phonology

Dr. Keith Rayner: What we find is that the orthography kicks in very quickly, so that over the whole priming interval that we look at the orthography, if the prime word is orthographically similar to the target word, you get some facilitation. But what’s really interesting to me is the phonology kicks in really quickly, too. I mean, it’s lagging behind the orthography only by about five or ten milliseconds, so that the orthographic information is getting in very quickly, but you’re quickly converting that to a phonological representation.

We’ve also done experiments, going back, now, to the first — to the paradigm I mentioned, where there’s just one change. So think of this: You’re reading and the word beach is your target word b-e-a-c-h. Now, before you get to that word, it could say, b-e-e-c-h, which is a homophone of b-e-a-c-h; or is could say b-e-n-c-h, which is orthographically very similar. Or it could just be another word like house, which is just totally unrelated to the prior word.

David Boulton: Right. Different levels of disruption to the expectation field that’s unfolding.

Dr. Keith Rayner: Yes. So, what we find is that you get facilitation from having the homophone, above and beyond having the orthographic control word, so that when people’s eyes land there, one of those things was there first, either the homophone beech or the orthographic control word bench or the unrelated word, or the identical word is there, so b-e-a-c-h could be there.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Keith Rayner: Then we look at: How long does it take to process this target word b-e-a-c-h as a function of what was there before? If the homophone was there before, you’re about as fast as if the identical word was there and you’re faster than if b-e-n-c-h was there. So before you get to a word, before the eyes actually fixate on it there’s a preview benefit; you get some facilitation of the upcoming word, and phonology, again, is kicking in very quickly.

David Boulton: So, is that suggesting, you think, that somehow the phonological processing is being primed?

Dr. Keith Rayner: Yes, the phonological information is being primed. You’re getting a head start on the phonological information before your eyes actually get to the word.

Keith Rayner, Distinguished Professor, Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts; Director of the University’s Eyetracking Laboratory. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/rayner.htm#MillisecondsBetweenOrthographyPhonology

Basic vs. Proficiency

David Boulton: Let’s discuss basic and proficiency. There’s a lot of conversation out there about which of these are important to understand to use as a benchmark in talking about the dimensions of the reading problem. There are also different interpretations of what is the actual definition of these two descriptions. Do you have anything you can say about the distinction between basic and proficiency and what they mean to you?

Dr. Louisa Moats: Tell me the distinction again.

David Boulton: Between being basically able to read and being proficient in reading. Right now, in the 2002 NAEP report, they’re saying eighty-eight percent of African American fourth grade children are below proficient and the average overall is sixty-four percent below proficient. What does that mean?

Dr. Louisa Moats: I think virtually it means that they avoid reading as adults and simply do not look to text as a source of information.

Louisa Moats, Director of Professional Development and Research Initiatives at Sopris West Educational Services; Author, Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers, Parenting a Struggling Reader, and LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling). Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/moats.htm#BasicvsProficiency