Automaticity

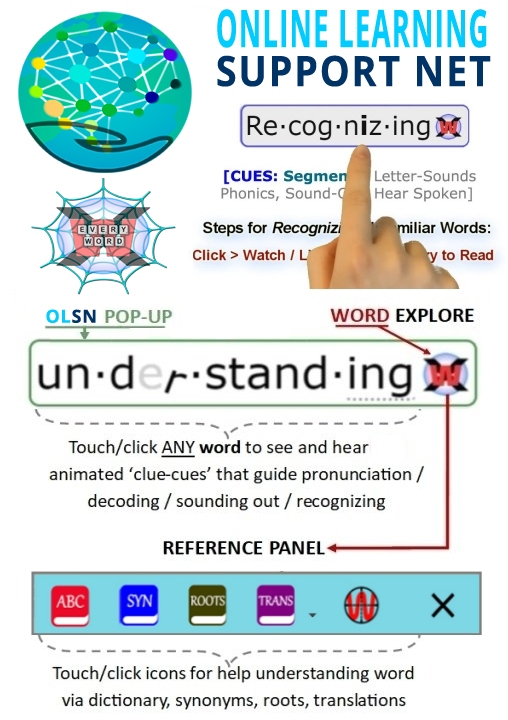

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Automatization

I think the crucial problem with all of language as we use it today is the problem with automatization. How do we take something that has so many variables, so many possible connections and combinatorial options, and do it without having to think about it? How do we turn this complicated set of relationships into a skill, ultimately, that can be run, in effect, as though it was a computation?

What we’re really doing is we’re taking something that is a nightmare for computation and as we mature both as language users but also as readers and writers, we have to automatize it so we don’t have to think about those details. The problem with automatization is that at any step, if you’ve got a slowdown step, if any piece of that enterprise has a block, where you can’t hold enough of the information, the whole house of cards falls apart. You can’t build beyond that point.

It looks as though, with the acquisition of language itself, speech particularly, that we’ve got a lot of redundancy in the system. We have work arounds that are there, probably evolved there, because it was so important and because there was enough evolutionary time behind that process to build in that safety net. With respect to reading and writing, there was no evolutionary support. With respect to reading and writing, there is no safety net. There are probably very few redundant work arounds that are successful that don’t take longer, that aren’t more clumsy – aren’t so clumsy that they drop something, they don’t keep track of it, or they’re simply too slow to keep up with your memory process.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#Automatization

Automaticity

David Boulton: When you said drop out a moment ago I was wondering if you mean that it falls into automaticity, it falls into being automatic and therefore it no longer requires conscious, volitional effort to workout; it’s now in the background and moving on to the next level of challenge.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: That’s right. And so for example we have an inordinate amount of attention and emphasis placed on, for example, phonology and phonemic awareness in the early stages of beginning reading and at kindergarten and first grade we rightfully spend a lot of time on that. But at some point phonemic awareness itself doesn’t become an enabling sub-skill, other variables come into play. Like at the word recognition level understanding and having a deep appreciation of the orthography, how those letters map on to those sounds, becomes a variable that causes maybe increasingly more divergence among readers than phonemic awareness. So as a developmental psychologist, we’re fascinated with looking at those trajectories and how those factors change.

Anne Cunningham, Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of

California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#Automaticity

The Matthew Effect

The Matthew Effect was described by Wahlberg and Sty and Keith Stanovich in the domain of reading. It essentially describes what happens to young children when we see the educational disparities that occur and the educational advantages. The Matthew Effect describes what happens over time when some children enter into a positive feedback loop, whereby those who learn to read and break the code with relative ease experience a positive affect and are able to read the text that they are given in schools with fluency. And that fluency develops a level of automaticity and because they develop automaticity with sounds and words they’re cognitive work space is freed to operate on the meaning of print, the purpose of why children are engaged in it. And so the world opens up to children who have that cognitive space left, who have automatized the code and words.

The converse of this Matthew Effect that Stanovich outlined in the mid 80’s where he developed a model of the educational have’s and have not’s in reading is a sadder tale. Those children who experience inordinate difficulty in breaking the code, who aren’t able to quickly assemble these sounds and put them into larger units we call words, and rapidly proceed through the sentences don’t develop the level of automaticity that allows them to have the cognitive work space available to them. As a result of that lack of automaticity, their resources are taken away and focused on the word level and they aren’t able to operate on the meaning.

Anne Cunningham, Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of

California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#MatthewEffect