Cognitive Consequences of Shame

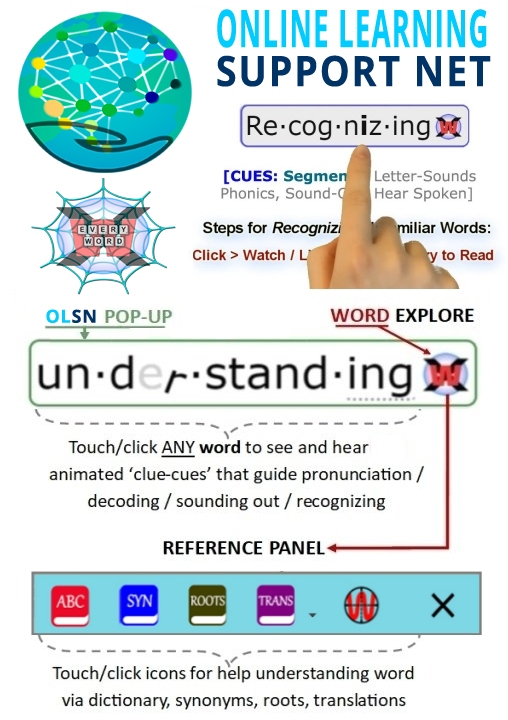

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Ambiguity, Shame and Cognitive Shock

Any acute interruption in the affect we call interest, (in a situation when it is logical for that interest to continue), triggers another physiologic mechanism that we call the physiology of shame or shame affect. Now this is not trivial because just as soon as shame affect is triggered it brings about in the mind of the child what we call a cognitive shock.

Scholars all through history have noted that the moment of shame makes them unable to think clearly. And this moment of cognitive shock is followed by other physiologic mechanisms: shoulders slump, the face is turned away from what a moment ago seemed interesting, and then we begin to reflect on other experiences we’ve had of this shame happening. Experiences of inefficacy, inadequacy, unpreparedness; all of a sudden our mind, our consciousness is flooded not with the printed material on the page, but flooded with a whole bunch of experiences that have to do with our worst possible self.”

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#ambiguityshamecog

Shame Consumes Bandwidth

David Boulton: And at the higher level, once shame kicks in it’s a bandwidth consumer.

Dr. Reid Lyon: It is. It is.

David Boulton: So, the moment they move into shame there’s a reduction of the processing bandwidth available to process the code.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Absolutely. Yeah. But your point about…this is what makes this so sad. G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#Shamebandwidth

Shame Disrupts Cognition

David Boulton: Right and that shame isn’t just a ‘we don’t want to have it’ feeling. It is fundamentally, to processing, cognitively disruptive. If somebody starts to associate shame with the process of learning to read, they have just made it a magnitude of order more difficult to learn.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Absolutely.

David Boulton: This is something, that in our travels, very few people understand.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Well, I would say that in general, educational pedagogy, educational curriculum have not paid much attention to the psychological dimensions of learning beyond the cognitive dimensions.

As one can come up with a sequence of material expectations for what children should learn and how they should learn it, and to the degree that those materials are well designed and the sequence is well designed, that’s an extremely important first step. But how to deal with errors, how to deal with failure along the way, how to maintain motivation to perform is an issue that we’ve paid less attention to than we should have, and that results in significant numbers of children who are turned off from the educational experience when it was entirely unnecessary that that be the outcome.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Director, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#ShameDisruptsCognition

Shame Disables Reading

I’m asking you to consider that there are two forms of cognition in the learning process. One is the neo-cortical brain, our most recent evolutionary adaptation, that lets us process information. It lets us correlate new things we’re learning to stuff we learned before. It lets us calculate, remember, store, associate, all those wonderful things about the neo-cortical brain. But there’s another part of the brain that is critical here, that’s the affect brain. What the affect system does is it focuses this new neo-cortical mechanism; it focuses on what needs to be done next.

So just as you can be really interested in whatever you’re studying and a book thumps in another part of the room and you and everybody looks over where the noise came from, when something ambiguous appears in front of us, a squiggle that makes no sense, a collection of letters that doesn’t as we say, read-out,our attention can lose focus on what we were interested in. When we are reading along and suddenly it stops making sense our flow becomes interrupted and we may frown and look away for a moment. What’s happened is that the attention to what we were reading became focused instead on the shame we felt about being confused.

When the child sees a stimulus on the printed page that can’t be deciphered for any reason, another spotlight takes away the spotlight of interest and that’s the spotlight of shame. Just like when that book dropped, the spotlight of startle distracted the child’s neo-cortical cognitive apparatus to think about what made that noise. The spotlight of shame forces us to think about our worst self, our defects, everything that has previously ever triggered shame. It is only with the greatest of strength that we remove ourselves from what shame focused us on, another spotlight, and we come back to being interested on the page.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#ShameDisablesReading

Shame Worsens Ambiguity

So shame is a response to an impediment to whatever we were doing that we were interested in. What happens when the moment of shame occurs? It causes what we call a cognitive shock. “No one can think clearly in the moment of shame,” Darwin said that over 100-125 years ago. Sartre said, “Shame always comes upon me like an internal hemorrhage for which I am completely unprepared.”

We’re unprepared because we were interested in something and to the degree that we were interested in it, we’re now feeling this horrible feeling of shame where we can’t think clearly. The spotlight of shame focuses us in a confused manner. That’s the job of that spotlight. Just like the spotlight of anger makes us focus angrily on something and the spotlight of distress makes us focus while weeping. Each of these affect spotlights has its function and the spotlight of shame makes us droop like this, turn away, and for a moment we can’t think.

As this happens to the child, the cognitive apparatus is turned off. If you can’t think clearly in the moment of shame, everything is working properly. The normal response to shame is to worsen the ambiguity.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#ShameWorsensAmbiguity

Ripple Effects of Reading Difficulty

I do see some very interesting ripple effects when kids are not acquiring reading skills. For example, it might be that a particular child in fourth grade is having difficulty keeping pace with reading comprehension or with decoding, and because he’s having trouble with reading, he hates to read. And when he does read, he gets almost nothing out of it because he’s reading very passively. And because he’s reading very passively, he’s not able to use reading as a way of building his language abilities.

So, what oddly happens is that his language problems caused his reading problems, and his reading problems are now causing much more aggravated language problems. Those language problems, in turn, are going to make it hard for him to follow directions, communicate well with other people, and even use language inside his mind for something called ‘verbal mediation.’ Verbal mediation is the process through with which you regulate your behavior and feelings by talking to yourself. And believe it or not, a lot of kids with language problems really don’t use language as a way of regulating themselves.

They get in trouble, they get depressed, because they don’t have a voice inside that says, ‘Yeah, I could take that medicine. I could take that drug from that kid, and hey I’m a cool dude. But oh, if I take it, I could like wreck my brain, and I could get addicted and my mother will kill me if she finds out, and I could get arrested.’ And all of that comes out of language, that sort of verbal conscience that’s guiding you.

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless.

Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

Shame, Self-Esteem and Neuromodulation

David Boulton: Have you done anything to actually isolate shame, develop a kind of signature of what shame looks like when it’s triggered in the brain?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: No. I’ve thought about it primarily from the point and read about it primarily from the point of, you could say, it’s obverse; which is self-esteem or positive self-awareness or self-healing and haven’t really thought about it as you raise the issue. It’s a wonderful thing to think about in the obverse. I’ve primarily thought and read about it in a sense in another thing that would reflect it and that’s the sort of the ongoing loss of self-esteem, of self-confidence, or in terms of self-doubting and what can be done about it.

David Boulton: I spent a lot of time in the self-esteem world before getting into the reading world. I’m interested in the reading world because of what it’s doing to self-esteem. Although I don’t like the term self-esteem, it’s got a lot of baggage with it.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: It does and it’s confusing.

David Boulton: I think of it as a buoyant absence of self-negativity rather than a positive accumulation….

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, exactly.You can have a boy that’s very self-confident, and yet in a sense, identifies himself in a broad domain as a failure and, in fact, his self-confidence is a kind of compensation. Actually, what I’ve really been interested in is the origins of bad conduct behavior because I think it would be a tremendously positive thing if we could understand it. Again, it relates to the development of emotional control and these complex reactions that occur in the brain that govern, in this overriding way, the general behavior of a child.

David Boulton: The sum of our view is this… We think that children are being overwhelmed with a form of confusion that is unnatural to them and they are learning to associate the feeling of that confusion with shame. We are all shame avoiders, escape artists; we don’t like to feel shame. So just as reading involves an assembly that’s faster than conscious, there’s a faster than conscious aversion to shame which is associated with feeling certain kinds of confusion, which in turn decapitates learning because learning involves extending through confusion.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: I love that description, although I don’t really understand its neurology. I love the description.

David Boulton: One of the things we’re trying to do is bring about some new explorations into the effects of negative affect triggering in the stream of cognitive processing. It seems to me it’s got to be dis-entraining.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, right. I think it’d be a great leap if you could understand that. I mean, if you have a child that enters school and the child fails at school,which means that they’re experiencing, they’re reacting in these ways to it and if they’re misbehaving, they have about an even money chance later in life to commit a felony. I mean the simple fact is we have to figure out how to get to those kids more reliably and more completely and it doesn’t necessarily involve cultural re-education. The more deeply we understand the neurology the more we could understand how to drive true correction of it.

David Boulton: Unless the neurology work embraces and includes the interdynamics between the more mechanically cognitive processes and the affectual processes that are orienting, contextualizing, powering, the cognitive activity, I don’t see how we can get there.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Well, I don’t know. I believe all these things are at some level accessible. Whether they could be, whether such training could be easily incorporated under conditions of something like a public school where an aspect of the training might include some level of social training, whether that’s really necessary or not, I don’t know.

David Boulton: Well, it’s also a matter of re-contextualizing the kinds of challenges that most trouble children so that they are less provoking of shame.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Well, one of the ways we’ve tried to design the software that we’ve applied to children, the training programs we provide to children, is to absolutely ensure a high level of success in every kid and this is a big part of it. A big part of it is to find ways in the course of every kid in a significant part of their life and day to ensure that they succeed in things. I mean one of the magic things that has to happen to every kid is they have to find something, something that they’re good at and everybody acknowledges and everybody tells them and they tell themselves. As long as you have enough of those things happening in your young life you can accept the things someone else is better than you at.

David Boulton: And the danger there is that it can be that the thing that I feel good about myself is that I can beat up everybody around me, right?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, I mean there is that. There has to be things outside of that realm.

David Boulton: All right. I think we’ve talked about many of the things we’re both most interested in. Is there anything that we’ve inspired in the course of our conversation, anything you’d like to touch on that we haven’t yet?

Dr. Michael Merzenich:Only to say that, this is a great quest. There is great hope that we can progress in understanding the neurological origins of things like this and the crucial dimensions as you’ve expressed, in this relationship between the emotional side of life and the overriding behavioral things that relate to neuromodulatory control in emotion.

I mean when you talk about neuromodulators and you talk about the things that condition learning, you’re also talking about the overlay of emotional baggage that comes with them, that are expressed with them, but also derive from them. You also talked about the fact that each one of us is basically creating the complex conditions under which they are constructed and they are inhabiting our heads and controlling our behaviors in our life.

One of the crucial things is to understand this complicated interplay between these modulators and understand how they evolve – how plastic they are. That’s been studied almost not at all. People have studied the axis of neuromodulation. Dopamine cells and dopamine chemistry has been manipulated in hundreds of ways partly because people see that there’s profit in it – to manipulate it because it’s so clearly involved in so much malfunction and so much disease in psychiatry and neurology. But still almost nobody has studied in any detail, or in any intelligent way, how this capacity, how this control, how this incredibly differentiated nuances of emotional control, as they influence learning and behavior are actually created and developed in an individual way and in an individual person. There’s high stakes in such understanding.

So, one of the things I think is evolving or will gradually evolve is a level of science in that area that will parallel the level of science in learning as it relates to the sort of dry side of learning, and that’s skill learning. As that evolves I think we’re going to generate more and more powerful ways to intervene in real human problems.

David Boulton: That’s excellent and that’s being echoed in other circles. Russ Whitehurst realizes that it is a weakness in the whole assessment paradigms of education. Other scientists that we’re talking to are also recognizing that this is a huge lacuna in our overall understanding and that it’s too significant to leave out of the equation.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, and not just for kids. It’s a big part of what we’re trying to do with older individuals. I mean with a seventy, eighty or ninety year old this machinery is now falling apart and you have to think about how you can reinvigorate it, revitalize it, re-enrich it. You know, we have to. People’s attitudes can be better. There are things that are rewarding to them and can be made stronger and more elaborate and they should be. It’s part of being healthier and happier in older age. And guess what emerges when you get older? Shame. What emerges is a lack of confidence. I’m now worried about whether I can succeed, whether I can keep my end up. I mean all of these things enter in again in spades.

David Boulton: That’s why I think it’s so important that we understand that there is a biological basis for the core affects and that shame seems to be, when we think about the human animal, a fundamental learning prompt, a really great thing. But if we become averse to the feeling of shame before it actually bubbles up, before we can think about it, it’s steering us away from what we need to learn about.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely.

David Boulton: And it seems to be happening on a grand scale.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right, right. It just basically shuts you down.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#ShameSelf-EsteemandNeuromodulation

Shame

David Boulton: So, we’ve got millions and millions of children growing up feeling ashamed of their minds and wanting to avoid confusion…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right.

David Boulton: Which decapitates learning.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. They don’t want to read because they’re not good at reading. They avoid reading. They’d rather clean the bathroom than read. Got it. Absolutely.

David Boulton: So, the interesting thing here is that not only is this all of the emotional trauma that we can imagine, but from a cognitive point of view, the moment this shame starting to trigger, it burns…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Yeah, that’s right.

David Boulton: The brain resources necessary to process the code in the first place and a downward spiral kicks in.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right.

David Boulton: The teacher has got to get this.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. Absolutely. That’s right. It basically takes the cognition hostage. It paralyzes the child. Absolutely. You’re right. It’s a tough one.

Edward Kame’enui, Past-Commissioner for Special Education Research where he leads the National Center for Special Education Research

under the Institute of Education Sciences. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/kameenui.htm#Shame