Decoding

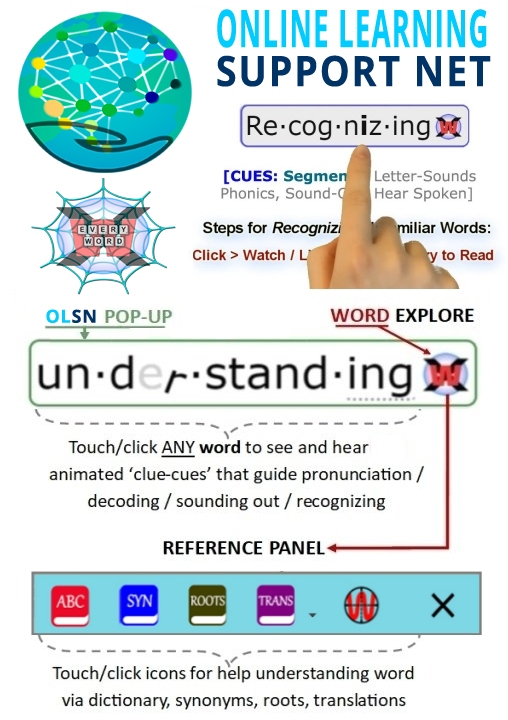

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Decoding and Comprehension

Robert Wedgeworth: There are two things that strike me about the material that you sent to me. One is that like most orientations towards formal education, we tend to put nearly all of our resources into teaching children how to decode, and we put very few of our resources into what is the more critical step, and that is developing reading comprehension skill. And the only way you develop reading comprehension skill is through continuing practice with increasingly more difficult reading material. And so we teach people how to read, how to decode, that is, thinking we’ve taught them how to read, not recognizing that reading is comprised of two very difficult skills. One is learning how to decode, and the other is developing the reading comprehension skill.

David Boulton: Well, my sense is — and I appreciate diving right into this, is that these two are very related. First of all, “decoding” is a misleading term. I mean, you could say that it’s decoding in a phonetic language, but when you talk about a written system that has such letter sound correspondence ambiguities, what we are really describing is disambiguation. It’s a process of buffering up these code elements and working out the right sounds for them according to the context in comprehension and the rules of spelling.

Robert Wedgeworth, Past-President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#DecodingandComprehension

Processing Stutters

David Boulton: There are two things that plug in here that I want to explore with you.

One has to do with assembly processing time. It’s clear in talking to the phonological side of neuroscience that fuzzy representations in the phonemic, phonological

dimensions require more processing time to disambiguate and cause a processing stutter – again purely on the auditory processing side.

To the extent that that’s true, then it seems equally true that the time it takes to disambiguate the code is also causing a processing stutter. This is one of the problems I have with terms like ‘alphabetic principal’ or ‘breaking the code’ because they over-simplify what we’d other wise call, more in the computer world so to speak, ‘disambiguation’, which is to take this stream of letters, some of who’s sound values depend on words that haven’t been read yet, buffer them up and construct these approximate word sounds from these fuzzy letter variables.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right.

David Boulton: And that the more time it takes to do that, just at that level in this module we’ve been describing as the language simulator, then the more that module is not delivering the language stream in time for comprehension.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yes, I think that’s right. Alan Lesgoldand I developed an idea that I put in my 1985 book about this. We called it code asynchrony; the idea being that orthographic phonological and semantic codes that had high levels of skill come out all at once. And in low levels of skill there can be an asynchrony in a sense that you’re getting some of the graphemes and some of the phonemes but you’re not getting the whole thing yet and things get all out of phase.Instead of mutually strengthening each other so that at the end of the decoding episode you have a stronger word representation that’s accessible by orthography, you’ve got bits and pieces and only partial success.

Now what you’re adding to that idea. I think specifically what you are saying is if the phonological space is too fuzzy because the letter hasn’t made phonological differentiations that turn out to be relevant for English vocabulary then that’s going to be an additional problem. There’s not going to be a differentiated phonological coding that comes out of any given word reading event. Then the question is how that develops.

Some of the pre-literacy research on children’s development of spoken language, I think, is suggesting that fuzzy phonological representations are normal and characteristic of early language development and that they become less fuzzy, more differentiated and more articulate only in response to increasing demands in the linguistic environment, which usually amounts to having to learn a new word or having to distinguish a new word from one that you already have and that can force you to make new phonological distinctions.

I think the fuzziness is normal and I think what can happen with reading when things are working well is that getting good feedback, either internally generated or externally, on a decoding attempt can have the same effect, that is forcing phonological differentiation. So, you can say an approximation. It doesn’t map onto anything that you know and so you either get feedback that it’s actually this word rather than that word or that the word that you’re trying to decode is novel and has its form and that produces new phonological representation. That, I think, is an interesting possibility for understanding this in general.

David Boulton: Right. So, they’re feeding into each other. I think at one level we’re a fuzzy processor in a myriad of ways.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I think you’re speaking formally, a formal idea of fuzziness, which is probabilistic category membership. That’s the formal sense.

David Boulton: Yes, but where I’m going with this is that to the extent that the time it takes to get from elemental recognition through disambiguation, through to an approximated word to move to recognition with… if that assembly takes too long then there’s a stutter that radiates through everything.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right, because it turns out you’re actually not assembling a unit that you can then use as a representation. Things are too disconnected.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I talked about this in terms of the theory of what it is that children learn to represent when they learn to read, something I called specificity representation. So that before acquiring specificity as a characteristic representation, I would put in these formal terms: it has variables instead of constants. Instead of always having this sound, it has sort of something like this sound or something like that sound.

David Boulton: It’s very much like a quantum wave collapsing to a particle in the context of the process.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yeah, maybe. I haven’t thought about that. That’s an interesting way. Okay.

Charles Perfetti, Professor, Psychology & Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/perfetti.htm#ProcessingStutters