It’s A Code

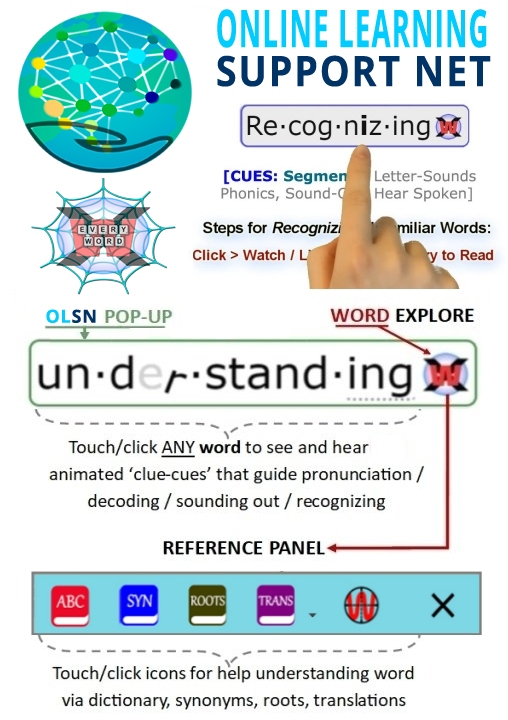

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

It's a Code

Reading is difficult for several reasons. One is that it’s a code and the code is not transparent. The relationship between letters and sounds is not necessarily natural and in the English language the code is made extraordinarily difficult by exceptions and rules and rules that are exceptions to rules. And so even when you’ve learned the code, you can end up not knowing how to pronounce something, not knowing how to sound something. So to begin with, we’ve got a difficult code.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#WhyisReadingsoDifficult

Orthography is Like a Big City

I look at English orthography perhaps as a tourist might look at a beautiful big city like Paris. Here’s a city laid out with Baron Haussmann’s wide avenues converging on a circle at the Arch de Triomphe. But then there are a multitude of side streets and dead end alleys and other patterns that intersect, interrupt, and occasionally complement. And I see the same thing in the orthography. In the same way the orthography has old and new. We have all these new spelling patterns for words like inputted and formatted. We use letter names like x-ray in words. At the same time we have good old Anglo-Saxon words like cow and sheep and raven and French borrowings in the same way that Paris has the newly remodeled Pompidou Center, the Foundation Cartier, other examples of modern and post-modern architecture along with the older parts of the city.

Richard Venezky, Past Unidel Professor of Educational Studies and Professor of Computer and Information Sciences, and Linguistics at the University of Delaware. He is the author of The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/venezky.htm#OrthographyBigCity

Important Distinctions in Orthography

Well, I’d say maybe the first and most important thing is that the orthography is structured. It’s not a chaotic mess, it’s not this damnable collection of accidents and historical mis-readings, but there really is a patterning there if you’re willing to tease it out. But that patterning derives from the fact that we have fifty some sounds and only twenty-six letters. So we have to adopt a whole variety of mechanisms to close the gap. One mechanism, very simply, is that we have two-letter and three-letter functional units, so if you want to understand how the orthography works first you have to define what the minimal units are, what I call functional units. Things like TCH and DG and CH and SH, where you couldn’t derive the sounds they have from the sounds of their constituent parts. That’s as small as you can get for those units. So that’s one factor.

Another factor is that, like many of the romance languages, we use what I call markers quite extensively. Markers are letters like the silent, final E, the U in guide, the doubled consonant in running, that themselves have no sound but point out how to pronounce something else or preserve a graphical pattern.

Another factor, going back to these functional units, is that some of them are what I call complex and some are simple. What that means is that spellings such as DG and CK and TCH and even X, when they have a single letter vowel spelling before them, that vowel spelling will always be pronounced with its so-called short pronunciation because these spellings operate as replacements for either two sounds like X or for a double spelling: CK is a replacement for KK, TCH is a replacement for CH doubled, and DG replaces GG. On the other hand, spellings such as SH and CH are simple. So in a spelling such as ache, the E signals a long vowel pronunciation of the A, while in a spelling such as axe, the E doesn’t signal a long pronunciation because the X is complex.

Another factor that has been pointed out for at least 200 years is that English, unlike Spanish and Finnish, tends to preserve the spelling of meaningful units with affixation and compounding, up to the point where translation to sound breaks down. As others have pointed out, we have electric and electricity, even though the C has two different sounds, and sane and sanity, even though the A has two different sounds. The ‘C’ and ‘A’ are retained in the spellings even though they change their sound values. This preserves the visual identity of the morphemes or meaningful units. English tries pretty hard to do this but doesn’t always succeed. But nevertheless, it’s a fairly modern principle that derives more from the 15th century than it does from the Old English period.

Richard Venezky, Past Unidel Professor of Educational Studies and Professor of Computer and Information Sciences, and Linguistics at the University of Delaware. He is the author of The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/venezky.htm#importantdistinctions