Alphabet Insight / Principle

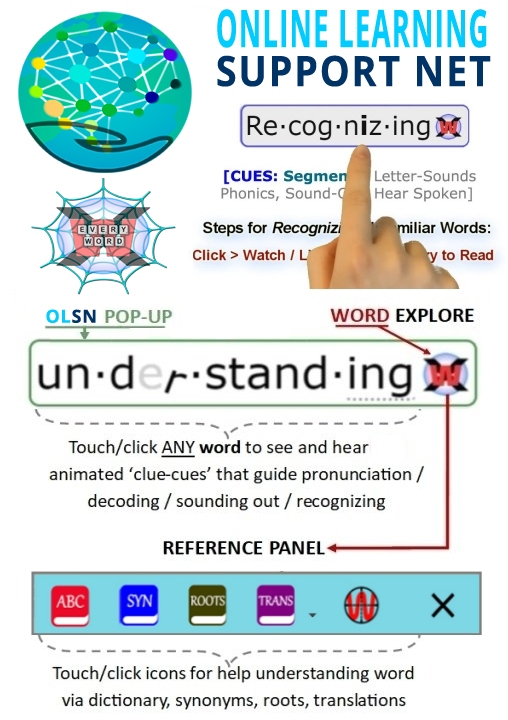

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Alphabetic Insight/Principle

David Boulton: People use that a lot, Dr. Reid Lyon uses that, as well as Dr. Whitehurst. It’s kind of suggestive of a singular event; ‘a principle’, meaning something that’s relatively stable, and once you get it, it’s there. Similarly, the word ‘insight’, means a singular event, right?

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Yeah.

David Boulton: But the correspondence between the alphabet and the sound system is anything but a single principle or a single insight.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. That’s fair enough. But there is a moment where, for the child who has not understood — like the child in Waimanalo, Hawaii, who will use words and not understand that words have a concrete representation until they see the concrete representation. And they’ll say, “Ah, I thought that word was this, but the word is not this, it’s that.” That’s an insight.

David Boulton: Right. To get that, there’s a fundamental correspondence between just speaking and writing…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right, exactly.

David Boulton: Thereafter…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Thereafter, yeah…

David Boulton: We’re talking about the development of these internal processing reflexes that create this virtual reality stream, which is an entirely different business.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. Yes, the insight is an important part, but it’s not all. You’re absolutely right.

David Boulton: When we look at the kids that are struggling on the downside, I mean, I would imagine that only a small percent of them are having a problem getting the insight. They’re having a problem on the other side of the insight trying to actually process the complexity…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Once they — yeah, that’s right, right, absolutely, that’s right.

David Boulton: and develop fluent code level processing.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. How do I continue to make the connection? That’s right. That’s fair enough.

Edward Kame’enui, Past-Commissioner for Special Education Research where he leads the National Center for Special Education Research

under the Institute of Education Sciences. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/kameenui.htm#AlphabeticInsightPrinciple

Interactive Compensatory Model of Reading

David Boulton: Let’s talk about your model of reading that we’ve referred to. Maybe you could describe some of the sub processors, some of the modules that are interacting here.

Dr. Keith Stanovich: I’ve given you parts of it. I mean, it’s the story that most people tell. Actually, I don’t want to call it my model anymore.

David Boulton: Okay.

Dr. Keith Stanovich: I’d like to call it the emerging consensus view, right? Of course, Anne has given you part of that foundational skills in phonological awareness. There’s a lot to know yet in the sense that people are still hotly debating the fractionating of that skill, what units are most important at what stages. There’s a lot left to be answered. But no one denies that a substrate of cognitive abilities in the phonological awareness domain is critical. Then that will get you nowhere without the basic alphabetic insight that print maps speech, and it maps, in English at least, at a fairly abstract and analytic level.

Then I saw a question of yours to somebody pointing out that we shouldn’t treat that as some type of zero/one thing, that developing orthographic knowledge is continuous. I couldn’t agree more.

David Boulton: I think that the alphabetic principle can be misleading, and that we’re talking about a complex disambiguation process.

Dr. Keith Stanovich: I think you’re absolutely right there. Part of this is just people getting sloppy with the language, in the sense that the alphabetic insight, that there’s some type of mapping here at a fairly abstract level, might be closer to discrete, but that’s…

David Boulton: That’s a first-step initiator to starting to learn your way into what are these correspondences.

Dr. Keith Stanovich: Exactly. And then, what is the structure of this code, as you rightly point out, and the complexity of this code? Then we’re talking about, yes, a long, unfolding process. Then very early in that process, I saw you talking with Anne about Matthew Effects, and very early in that process those effects start to kick in. I see that part of your interest in this series is the consequences of the acquisition of literacy. Those consequences feed back on the act of acquisition itself and they ripple out into other cognitive structures, processes and tools, like vocabulary.

Keith Stanovich, Canada’s Research Chair of Applied Cognitive Science at the Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology, University of Toronto. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/stanovich.htm#InteractiveCompensatory

Speed of Processing

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: One of the things that is so critical is that our brains only allow so much stuff to go on at one time. The faster and easier you can do some tasks, the more room you have to do other ones. So, this notion of if I can recognize the words quickly and easily then when that other person starts asking me these scientific questions I can struggle with that, I can really focus on that. I’m not going to be so tied up with phonemic awareness and phonics – is that a /f/ sound? I mean, they’ve lost it by then.

David Boulton: One of the things that we notice is there is a very definitive, first-person, observable correspondence between the articulation stutters of a struggling reader and the code confusion that they’re actually encountering at that part of the stream of reading.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Oh, no doubt about it. And so again, all four of those things need to be taught and they need to be taught at all levels. If students don’t learn to recognize words and decode, and to turn the letters into language, all the rest of the process is at great risk.

David Boulton: Right. This is one of the differences that we explored with Reid Lyon – it’s often called the alphabet principle or the alphabetic insight; as if there was some principle to grasp, after which this processing would work.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Right.

David Boulton: Which doesn’t seem at all an appropriate way to think about it. What we’re talking about is faster than consciousness, unconscious processing reflexes that have got to recognize a letter and put it into a kind of buffer space where it’s got to reside, hanging in time, while other information comes in and is applied from other sections of the brain to disambiguate that letter’s actual sound rather than its field of potential sounds, and assemble a recognizable whole word for comprehension to pick up and move with.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: That’s exactly right. What you’re describing is incredibly complex and it almost sounds so complex that it would be unteachable. The fact is that it’s very teachable.

David Boulton: It’s very teachable. Yes, I think so, too.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#BrainCapacitySpeedofProcessing

More than a Principle

David Boulton: Absolutely. I’d like to circle back to that, but before we move there, the other thing that seems to be missing is some discussion about the spectrum between basic and proficiency.Most people would say that people below basic have not gotten the alphabetic principle with the caveat we just put on it.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: For the most part that’s true.

David Boulton: So, then we could say that the people below proficiency may have gotten an instrumental ability but it’s not all happening fast enough to create transparency and an ecology of processing that will leave enough energy left over for the subsequent processes to comprehend and act on. So, code processing runs the spectrum.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely. It’s not just knowing it (the code), it’s knowing it at a level and speed and facility that allows you to automatically, without conscious attention, fire these routines off.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#MorethanaPrinciple

Processing Stutters

David Boulton: There are two things that plug in here that I want to explore with you.

One has to do with assembly processing time. It’s clear in talking to the phonological side of neuroscience that fuzzy representations in the phonemic, phonological dimensions require more processing time to disambiguate and cause a processing stutter – again purely on the auditory processing side.

To the extent that that’s true, then it seems equally true that the time it takes to disambiguate the code is also causing a processing stutter. This is one of the problems I have with terms like ‘alphabetic principal’ or ‘breaking the code’ because they over-simplify what we’d other wise call, more in the computer world so to speak, ‘disambiguation’, which is to take this stream of letters, some of who’s sound values depend on words that haven’t been read yet, buffer them up and construct these approximate word sounds from these fuzzy letter variables.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right.

David Boulton: And that the more time it takes to do that, just at that level in this module we’ve been describing as the language simulator, then the more that module is not delivering the language stream in time for comprehension.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yes, I think that’s right. Alan Lesgoldand I developed an idea that I put in my 1985 book about this. We called it code asynchrony; the idea being that orthographic phonological and semantic codes that had high levels of skill come out all at once. And in low levels of skill there can be an asynchrony in a sense that you’re getting some of the graphemes and some of the phonemes but you’re not getting the whole thing yet and things get all out of phase.Instead of mutually strengthening each other so that at the end of the decoding episode you have a stronger word representation that’s accessible by orthography, you’ve got bits and pieces and only partial success.

Now what you’re adding to that idea. I think specifically what you are saying is if the phonological space is too fuzzy because the letter hasn’t made phonological differentiations that turn out to be relevant for English vocabulary then that’s going to be an additional problem. There’s not going to be a differentiated phonological coding that comes out of any given word reading event. Then the question is how that develops.

Some of the pre-literacy research on children’s development of spoken language, I think, is suggesting that fuzzy phonological representations are normal and characteristic of early language development and that they become less fuzzy, more differentiated and more articulate only in response to increasing demands in the linguistic environment, which usually amounts to having to learn a new word or having to distinguish a new word from one that you already have and that can force you to make new phonological distinctions.

I think the fuzziness is normal and I think what can happen with reading when things are working well is that getting good feedback, either internally generated or externally, on a decoding attempt can have the same effect, that is forcing phonological differentiation. So, you can say an approximation. It doesn’t map onto anything that you know and so you either get feedback that it’s actually this word rather than that word or that the word that you’re trying to decode is novel and has its form and that produces new phonological representation. That, I think, is an interesting possibility for understanding this in general.

David Boulton: Right. So, they’re feeding into each other. I think at one level we’re a fuzzy processor in a myriad of ways.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I think you’re speaking formally, a formal idea of fuzziness, which is probabilistic category membership. That’s the formal sense.

David Boulton: Yes, but where I’m going with this is that to the extent that the time it takes to get from elemental recognition through disambiguation, through to an approximated word to move to recognition with… if that assembly takes too long then there’s a stutter that radiates through everything.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Right, because it turns out you’re actually not assembling a unit that you can then use as a representation. Things are too disconnected.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: I talked about this in terms of the theory of what it is that children learn to represent when they learn to read, something I called specificity representation. So that before acquiring specificity as a characteristic representation, I would put in these formal terms: it has variables instead of constants. Instead of always having this sound, it has sort of something like this sound or something like that sound.

David Boulton: It’s very much like a quantum wave collapsing to a particle in the context of the process.

Dr. Charles Perfetti: Yeah, maybe. I haven’t thought about that. That’s an interesting way. Okay.

Charles Perfetti, Professor, Psychology & Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/perfetti.htm#ProcessingStutters