Auditory Conceptualization

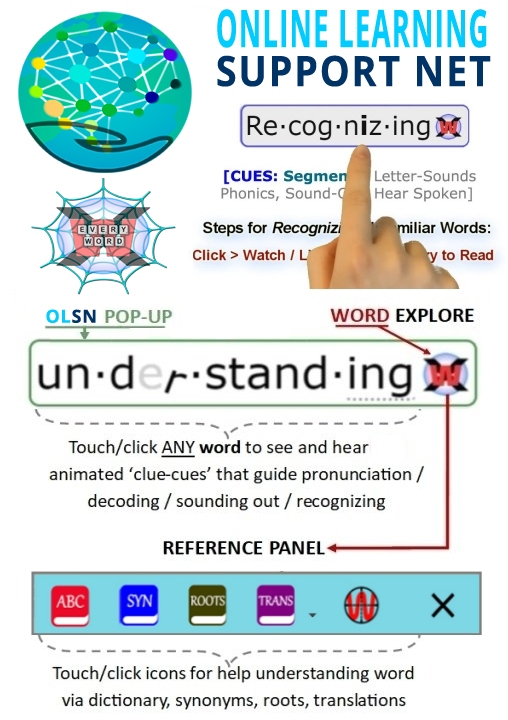

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Lindamood Auditory Conceptualization Test

Pat Lindamood: I began to have some leadings as to what was making a difference for them. And it had to do with their ability to be consciously aware of individual sounds, the phonemes of the language, and whether two were the same or different, and when they were put together into syllables and words, that they could not judge the identity or the number or order of them.

David Boulton: So you had a first-person experience in your work with them about the importance of the whole phonemic awareness distinction that’s become so much a part of the conversation today?

Pat Lindamood: Yes. And at that time, the only test of that type was Wepman’s Auditory Discrimination Test. And it was a good test for what it was asking, but the question it was asking, I felt, was too gross. It was just asking when two syllables were presented, the person being tested had to tell if they were the same or different. And it seemed to me that what was needed was that the mind would be able to say how they were different and whether they were different, if you were going to want to connect into the alphabet system.

David Boulton: Right. At the level of granularity of the kind of sound distinctions that have to map to the letters.

Pat Lindamood: Right, and particularly the sequence in which they had to be. And so as a result of the need to determine where to put my effort with them, why, my husband — whose field was linguistics — and I developed a system for having them show us. Because I couldn’t understand what the retarded girl said, I had to have a way for her to show me her judgment of sameness or difference in number and order. So we developed a way to use colored blocks for them to do that. And that ultimately became a published test, the Lindamood Auditory Conceptualization Test.

And it showed me where I had to put some effort with those girls, because the retarded girl could judge some isolated sounds as same or different, and others that were different, she judged as the same. So when we put them into a syllable, she couldn’t make judgments at all. The other girl, who was not retarded — and the retardation doesn’t have anything to do with this phoneme awareness…

David Boulton: This aspect of it, yes, right.

Pat Lindamood: It’s not related to intelligence. But the other girl could do just the isolated sounds perfectly accurately when they were in patterns. But when those same phonemes were placed in syllables, and then when I added or omitted or substituted or shifted a phoneme, or repeated one within the pattern, she could not judge that at all. So I saw I had to start at a common level, but that I could expect to move more rapidly with one girl than the other.

Pat Lindamood, Founder, Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lindamoodbell.htm#LindamoodAuditoryConceptualizationTest

Auditory Conceptual Judgment

Pat Lindamood: So I began to try to make those kinds of contacts and share what I felt I had some beginning understandings of. And I called this problem “auditory conceptual judgment,” because the term “phoneme” was not in the vocabulary of educators at that time, and they wouldn’t have known what I was trying to talk about.

David Boulton: Right. You could only talk to your husband about that one.

Pat Lindamood: Right. But I wanted it to be more than just the auditory discrimination that Wepman had called to attention, and so that’s why I called it “auditory conceptual” function.

Pat Lindamood, Founder, Linda mood-Bell Learning Processes. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lindamoodbell.htm#AuditoryConceptualJudgment