Below Basic, Basic, and Proficiency Spectrum

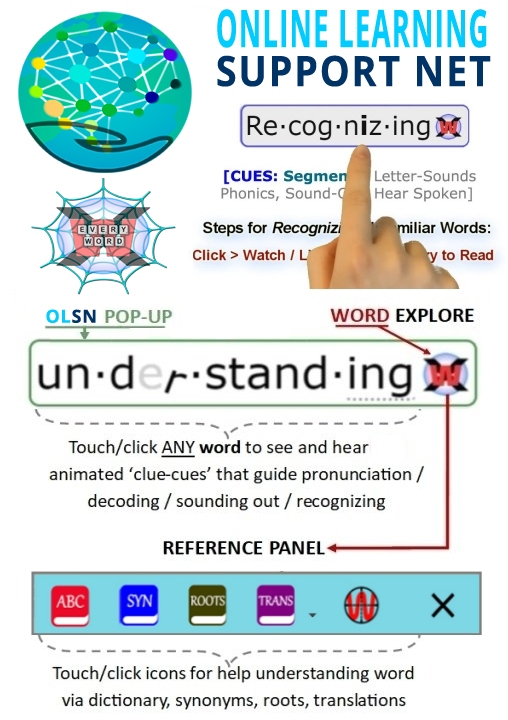

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

According to the 2011 national report cards on reading by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), most of our children are less than proficient in reading even after 12 years of our attempts to teach them:

|

African American

4th grade 51%

8th grade 41%

12th grade 43%

Hispanic

4th grade 49%

8th grade 36%

12th grade 39%

American Indian/Alaska Native

4th grade 53%

8th grade 37%

12th grade 30%

Asian/Pacific Islander

4th grade 20%

8th grade 17%

12th grade 19%

White

4th grade 22%

8th grade 57%

12th grade 19%

|

|

African American

4th grade 84%

8th grade 85%

12th grade 83%

Hispanic

4th grade 82%

8th grade 81%

12th grade 78%

American Indian/Alaska Native

4th grade 82%

8th grade 78%

12th grade 71%

Asian/Pacific Islander

4th grade 51%

8th grade 53%

12th grade 51%

White

4th grade 57%

8th grade 57%

12th grade 54%

|

Note: Data from NAEP 2011 Report

The Difference Between Basic and Proficient

David Boulton: In addition to the two ‘book end’ categories, basic and advanced, there’s a middle category called proficiency. While there’s 38-40% in fourth grade that are below basic, the numbers go to sixty-eight percent that are below proficient. What is the difference between basic and proficiency?

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Someone who can read at the basic level can take age appropriate text, and the assessments that we use are generally assessments based on natural texts, the sort of books that children would be assigned in the classroom. Someone who is reading at the basic level can understand the words, can answer simple questions about the factual information presented in the written text and can read with enough fluency to get through the material on time and answer questions. Students who are performing at the proficient level can go beyond that to make reasonable inferences from the material they read.

So, if the written material was about a thief and the thief stole something, someone who is reading proficiently can make inferences about what that must have felt like for the person whose materials were stolen and what the thief might do next, or why the thief was engaging in thievery to begin with. They are able to comprehend a deeper sense of the written material.

David Boulton: So, instead of a kind of instrumental or more superficial basic level, proficiency is the level we would at minimum expect or ideally like to have of kids that can actually translate what they’re reading into some kind of more vibrant, real experience.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, yes. The National Assessment for Education Progress, which is the assessment device that we’re talking about here, defines proficient in that way. It comes at a definition of proficiency based on a national process of collecting input from teachers and reading specialists and others and deciding what should a fourth grader know to be considered to be proficient.

What you’ve just described, which is the ability to comprehend in some sense what’s read, to go beyond that and to use the material, is the underlying definition of what it means to be proficient.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#BasicProficient

Code Processing Inefficiency Drags Comprehension

David Boulton: Related to the difference between basic and proficient, as you’ve just described it, is that ‘below basic’ is a fundamental inability to process the code and ‘below proficient’ is a less than optimal ability to translate that code processing into comprehension.

So, ‘below proficiency’ represents this less than optimal comprehension of what has been decoded in processing. There’s a number of pieces of work that I’ve encountered that suggest that though people may have ‘broken the code’, the processing efficiency related to how they’ve learned to process the code is dragging down the cognitive processing resources resulting in this drag on comprehension.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes.

David Boulton: So, the code, while ‘breaking it’ we might say is a problem below the basic level, processing the code as a whole is central to this whole field (below basic through proficiency).

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Absolutely. Children who perform at the proficient level not only can understand the words that they’re reading and the paragraphs that they’re reading, in the sense of bringing to bear information from their own experience, other classes, reading, home and background to bear on what they’re reading; but they also read fluently. That means they’ve broken the code; they can turn letters into sounds at a level that doesn’t really require conscious processing anymore.

It’s like the child who has learned to ride a bicycle and really has learned to ride it. That child is not thinking about where her feet are on the pedals and how quickly she has to turn the pedals around and whether her hands are on the brake or not. That part of the process has been over learned and the child doesn’t even have to think about it anymore, and can now think about where the bicycle is going and why the trip is going to be taken and whether she should be going fast or slowly.

Children who have really broken the code have moved to fluency. The whole process of dealing with the code is now occupying a different section of the brain; it doesn’t require a lot of thought and allows them to go on and think about what they are exposed to, what they are reading, what’s written on the page and what it really means.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interviewhttp://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#CodeInefficiencyDrags

The Basic - Proficiency Spectrum

David Boulton: What’s your sense of the difference between basic and proficiency, and what importance do you give to it?

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Well, those are nominal distinctions that we use in terms of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. A lot of states make that distinction between basic and below basic, and then proficient, and then advanced, and so on. I suppose what that means in the general sense is basic means that they’re reading at grade level. Below basic means they’re reading below grade level. Proficient means they’re reading beyond — they’re able to negotiate the grade-level materials in a way that they can use their thinking flexibly, they can make inferences that go beyond the text, and so on.

To me, that’s less than helpful, because to me it’s not about basic and below basic. What’s critical is what’s the criterion level of performance that’s required, the minimum criterion level of performance that’s required for kids to read at a level that will predict their ability to read in the future. So, it’s a predictability, longitudinal framework that I’m looking at.

Edward Kame’enui, Commissioner for Special Education Research where he leads the National Center for Special Education Research

under the Institute of Education Sciences. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/kameenui.htm#BasicProficiencySpectrum

Most of Our Children are Below Proficient

David Boulton: The National Reading Report Card says that almost sixty-eight of fourth graders read below proficiency.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: When sixty-eight percent of fourth graders are below proficiency we know that the odds, the probability of those children catching up and becoming proficient readers in four years from there, or by the time they graduate from high school are very slim. Part of the problem is that we know statistically that if a child is below proficiency by fourth grade then they’re probably not going to become a proficient reader. We actually know that in first grade. We know that the probability when a child is in the lower quartile, unless something very different is done for them in the educational system, that they’re going to experience that drop out in literacy.

David Boulton: Sixty percent of twelfth graders are still below proficient. That’s one of the most amazing things: sixty-eight percent of fourth graders and still sixty percent of twelfth graders are below proficient. So, this is not basic. This is a higher level than that. But still if we say that so much depends on the cognitive exercise, on the Matthew Effect and so forth, what we are saying is that most of our children aren’t doing that well.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: That’s right. And if most of our children are at that lower level, of basic level and aren’t proficient in reading, what are the odds that they’re going to be readers as adults? What are the odds that this is going to be a life long habit that they’re going to pick up after high school? They’re slim to none that they’re going to engage in print in ways that enrich their life, that add to their life across multiple domains. I mean there’s so much to be gained by reading a novel or reading a biography; the multiplicity of places that you could go in print that you couldn’t get to any other way are enormous. So, in terms of satisfaction in adulthood, books and print offer so much that just aren’t available to these students who only achieve this basic level at the end of their public school.

Anne Cunningham, Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview: –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#belowproficient

Basic vs. Proficiency

David Boulton: Let’s discuss basic and proficiency. There’s a lot of conversation out there about which of these are important to understand to use as a benchmark in talking about the dimensions of the reading problem. There are also different interpretations of what is the actual definition of these two descriptions. Do you have anything you can say about the distinction between basic and proficiency and what they mean to you?

Dr. Louisa Moats: Tell me the distinction again.

David Boulton: Between being basically able to read and being proficient in reading. Right now, in the 2002 NAEP report, they’re saying eighty-eight percent of African American fourth grade children are below proficient and the average overall is sixty-four percent below proficient. What does that mean?

Dr. Louisa Moats: I think virtually it means that they avoid reading as adults and simply do not look to text as a source of information. I don’t make this public a lot, but one of the astonishing phenomenon that I encountered when I was conducting research in the Washington D.C. school system was that the adults I was working with, who often were products of that school system, who may themselves have never gotten beyond a fourth grade level but got through school somehow, they never read memos, they never sent memos, they never used the internet. The only way we ever got anything done was if I personally went around and talked to people face to face and reminded them of when we had meetings.

Louisa Moats, Director, Professional Development and Research Initiatives at Sopris West Educational Services; Author, Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers, Parenting a Struggling Reader, and LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling). Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/moats.htm#BasicvsProficiency

More than a Principle

David Boulton: … the other thing that seems to be missing is some discussion about the spectrum between basic and proficiency. Most people would say that people below basic have not gotten the alphabetic principle with the caveat we just put on it.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: For the most part that’s true.

David Boulton: So, then we could say that the people below proficiency may have gotten an instrumental ability but it’s not all happening fast enough to create transparency and an ecology of processing that will leave enough energy left over for the subsequent processes to comprehend and act on. So, code processing runs the spectrum.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely. It’s not just knowing it (the code), it’s knowing it at a level and speed and facility that allows you to automatically, without conscious attention, fire these routines off.

One of the things that’s remarkable about it is when you look at what it is that somebody must do. If you do some kind of a logical analysis of print and map how that would go into the brain and use what we know about how much information the eye can pick up at a time, and so on, you’ll come to a picture of people able to look at every letter, see these patterns within words and know what that means in terms of their sound values and turn that into oral language and then interpret that in a way that they would oral language. It’s fairly linear, it’s fairly straight-forward and it seems like, oh okay, let’s just teach kids those patterns and let’s teach them the relationships and it’s going to be fine.

But when you actually look at it, the language is much more complex than anything that we would ever try to teach. The fact is that there are many more patterns in the language, there are many more sound relationships with the letters that we don’t ever get to simply because you don’t need to. The most elaborate phonics programs don’t teach more than sixty to one hundred patterns and sounds.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#MorethanaPrinciple