Paradigm Inertia: Adult Bias About Code Ambiguity

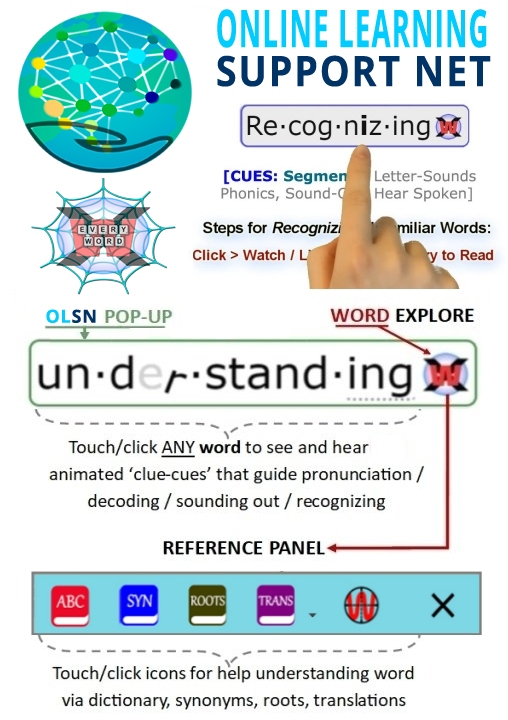

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Alphabet Wasn't Created for English

David Boulton: But today the struggle that our children face in learning to read is that there’s a lot of, at least as perceived by them, confusion and ambiguity in the relationship between letters and sounds.

John Fisher: Because the alphabet wasn’t created for English.

David Boulton: Right. And these scribes that were mapping the alphabet to the English spoken language weren’t very concerned about the ecology of processing the resulting code for the masses of humanity that would come later.

John Fisher: Well see, everybody who knew how to read and write until about 1600 learned to read and write in Latin and then tried to apply that to English. Nobody learned to read and write in English until well after the Renaissance.

John Fisher, Medievalist, Retired Professor Emeritus of English at University of Tennessee, Author of The Emergence of Standard English. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/fisher.htm#alphabetwasnt

Letter Sounds Behave Differently in Different Environments

Letter sounds behave differently in different environments. If you’re doing systematic phonics and you’ve only gotten up to L — suppose you do letter of the day and you’ve only gotten up to L, and you ask children to write about their Halloween costume? Did you ever see a kid doing inventive spelling who only used the letters A through L? Never. You really want them to think. So if I taught cat, hat and fat, I do want them to figure out what sat is, you know?

David Boulton: And the point is to be able to generalize on any one of the letter sound combinations and understand the patterns.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Exactly. ‘I’m teaching you examples and you’re learning to think. Now, this is your job. This isn’t my job. You think. You think for you. I don’t think for you. I teach. But I watch to see if you’re thinking well.’

States like Texas and California define everything in terms of single letter sound, which totally gets people back into the1950’s. Even if they’re not thinking that way, the instructional materials come out in that SR Learning Theory kind of thing where everything is in a very closed system. But then the opposite side of having it defined that way is when you look at the decodables that get passed by the adoption committees. They start using letter sound correspondences without any consideration of number of syllables.

David Boulton: One of the things that we’ve developed was a way to look at the variations of — in other words, the number of possible sounds that a letter can make in a particular vocabulary set. We looked at the vocabulary lists, and it’s amazing to me how confusing the words are that are in these vocabulary lists.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: In terms of letter sound correspondences?

David Boulton: And in terms of what you were saying, the number of syllables. What’s missing is an understanding of the levels of ambiguity-challenges involved and the question: ‘How can we help children step-by-step through being able to process these different kinds of ambiguity-challenges on the road to reading?’

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Exactly. At the first level there are these consonants, then vowels. You’re going to do the short vowels, and you read them left to right, and sound them out, and that’s the way the word goes. Fine.

Now we have these long vowels. How will we do this? Remember, these vowels are very special letters, but they need help to say their names. So then you do the — thank God there’s the final e convention. It’s pretty straightforward and very generalizible, because you can do lots of contrasts to make them think, and make them think about which sound they’re hearing and if it’s a this and if it’s a that, and real usage, because the vowel diagraphs really stink. I hate them, you know?

That’s another case where there’s just no substitute for visiting it. This isn’t going to come through experience. I can’t tell you how many curricula I’ve picked up where they say, ‘Okay, we’re doing long /ee/, so let’s teach final e. The magic e thing, and let’s teach ee, ea, and ie, and maybe final y, too. Why not? It says /ee/, too.’ So they present all those things. I hate this. Then instantly after presenting these as single letter-sound correspondences, they give the children a dictation test and count them wrong.

How are the kids going to know when to use ee and when to use ea? If they could do this, why would you have needed to teach this lesson? Don’t put the ea in the same lesson; just do the final e and get that done with all the vowels. Once we have the contrast down, we’ll work on the other ways to spell long vowels.

Convince them. Keep the con game up. There are lots of things you do as a grownup. Like you teach them that they have to say please to get what they want. And you know what? That almost never works in real life. You still teach them to though.

You want them to have these basic frameworks, like the alphabetic system, like, ‘Vowels need help to say their name, this is one way they do it. Here’s another way they do it.’ When they get to second grade, the kids who are coming along will say things to you like, ‘Uh, this shouldn’t be begin, this should be bejin, ha ha. This should be jiggle, not giggle, ha ha. This should behave.’

They think that’s very interesting. So there’s give and have and glove. Next?

It’s parenting. It’s about conning your children.

Marilyn Jager Adams, Chief Scientist of Soliloquy Learning, Inc., Author of Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/adams.htm#BacktoAmbiguity

Ambiguity vs. Variability

One thing you’ve clearly got to learn is a set for flexibility. You’ve got to learn that if you’re looking at let’s say sane and you first say san and that doesn’t make any sense in the context, you’ve got to change something and try again. That letters have some variability, vowels vary much more than the consonants, there are clues that you might be looking for in the word. Part of the teaching of decoding is teaching this set for variability. And it comes with great difficulty for certain kids.

David Boulton: To come back to where we started, you originally started off with a hesitation on the word ambiguity.

Dr. Richard Venezky: Right.

David Boulton: And my use of the word ambiguity would come right into where we are now with respect to the variability. And how is it the variability goes from what’s possible, which is complex, to what’s actual in order to make this recognition happen?

Dr. Richard Venezky: I wouldn’t call it ambiguity. It’s not a bad term. It’s certainly acceptable. But for the first place, there are patterns that are simply complex. They’re not ambiguous in the true sense of the word.

David Boulton: We could then say ‘ambivalent’ because the experience is ambivalence.

Dr. Richard Venezky: Well, I’m not sure I’d even want to say that because that’s making an implication of how these things are handled. Take a word like city. C at the beginning of the word before E, I or Y is soft like city and cent. Now there’s nothing ambiguous about it. If it’s before one of those letters…

David Boulton: But if you don’t know those rules when you encounter the C…

Dr. Richard Venezky: Ahh.

David Boulton: Then it’s ambiguous.

Dr. Richard Venezky: Well, sure.

David Boulton: Well, that’s the whole point! We’re talking about the child’s perspective struggling to learn to read.

Dr. Richard Venezky: But the orthography is not ambiguous.

Richard Venezky, Past Unidel Professor of Educational Studies and Professor of Computer and Information Sciences, and Linguistics at the University of Delaware. Author, The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/venezky.htm#AmbiguityvsVariability

Ambiguity Processing Takes Time

What’s interesting is that different languages have more or less transparent orthography. Orthography is the letter system. Now it’s interesting that in some languages there’s really a one to one relationship between the letter and the sound it makes. Spanish is one of those languages. There’s a letter, there’s a sound. And once you’ve learned those letters and those sounds you can read just about any words that you want in Spanish, probably any words you want in Spanish correctly. Even if you don’t understand any of them you can at least pronounce them correctly. English is on the other end of the spectrum it seems with lots and lots of exceptions. I mean, who came up with E-N-O-U-G-H spells enough? It should be E-N-U-F. So, English has many, many exceptions and that of course adds additional complexities.

What I’ve described in terms of this road block, as it were, in the use of the acoustic information which is coming into the brain very quickly in time and having to have that separated out and come up with nice, neat phoneme categories so that you can have those neurons that are firing together wiring together and getting really solidly wired – that’s going to work really well if you’ve got that all wired up for a system like Spanish. And it’s going to work well for English. But it’s not going to work perfectly for English because there’s a whole lot of additional stuff that you have to pull in. So, English is going to be a much more difficult language and therefore we are probably going to have a lot more children struggling to learn it because there are additional brain processes.

The reality is that if you look at these newer technologies that are able to image the brain in real time – not just take a picture of what lit up and subtract it out from everything else, but really follow using full head evoked potential or magnetoenchephalography or something that can actually follow the response – in general, a lot of the brain is working to process information as complex as speech. And when you get into reading where you’ve got the language plus the written part to be decoded and reassembled and comprehended, we are really using a lot of parts of our brain.

But the truth is that reading is one of the more complicated of the higher cognitive functions using attention and rate-of-processing and sequencing and memory and the linguistic systems and the visual system and it’s having to coordinate this dance that’s going on. And the more complicated the translation from the orthography to the phonology is to a particular language, the more complicated this processing dance has to be within the brain,

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#AmbiguityProcessingTakesTime

Articulation Stutters and Code Ambiguity

David Boulton: The hesitation, the slow processing that we were talking about before…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yeah, yeah.

David Boulton: Seems to correspond to the ambiguity. In other words, if you track a child’s articulation…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yeah.

David Boulton: As they’re flowing through the reading stream you can see the bog happen in direct correspondence to the code’s knots.

Dr. Reid Lyon: You can, you can. Absolutely. And this underscores the need for teachers to know where the ambiguities are…

David Boulton: Right.

Dr. Reid Lyon: To know the sequences that are most efficient to move kids to mastery…. And if you look at the instructional programs that are most beneficial for kids at risk, that really do get swallowed up by this ambiguity, those instructional programs carry a sequence of presentation designed to move kids systematically…

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates.

Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#stutterscodeambiguity

Levels of Ambiguity

David Boulton: All of these things you could say are different levels of ambiguity, right?

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Right. For example, we have one where ‘The lions were walking up and down and switching their tails.’ And the kids, the weaker second grade readers, have to sit there and figure the whole word out. And they can read — even the ones who have words like switch — just take forever because they don’t get a full duplex on it. ‘Switch your tail, switch, switch? Switching what?’ But the good readers just plow right through it. ‘The lions are walking up and down and switching their t—‘ And then they go right back and go, ‘That can’t be right. Switching their tails with whom?’

David Boulton: Right. That’s because they’ve developed a certain solid inner reference for their prediction system about what’s right.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: That’s right. But they did get so they could read that word automatically, and that check didn’t get there until after they’d done it. Whereas, the kids who are working on it, they needed the full duplex. It never got there when they were finished. Then there are the other kids who have to sound it out, and they just work. They work, they work, they work. It’s so much work, so much work to be a little reader. There are so many pieces that have to go together. Watch the body language.

Marilyn Jager Adams, Chief Scientist of Soliloquy Learning, Inc., Author of Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/adams.htm#LevelsofAmbiguity

Code Ambiguity

Dr. Michael Merzenich: I think what we’re both saying is the same thing really. We’re saying that it’s a miracle that it ever happens. It’s an incredible human capacity. It’s hard won by incredible depth of practice. It’s very unsurprising that many people struggle with it. I mean you wouldn’t have to have much a fault in this machine operating with high speed in this incredible processing efficiency that’s required to begin to see somebody be a little slower at it or a lot slower at it. And so therefore, dyslexia, in a self-organizing machine of this nature, is an expected problem. It’s an expected weakness. It should apply very widely.

David Boulton: In addition to the underlying sound processing issues we talked about earlier, wouldn’t the trouble also be related to the confusion in correspondence between letters and sounds? That the more brain time it takes to resolve the ambiguity…

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely .

David Boulton: The greater the stress on the system to produce…

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Make the representation of the sound parts of words a little fuzzy and it’s going to slow down the ability. And as soon as you do you also have a decline in processing efficiency, the ability to hear something and rapidly translate it or to do anything with it has slowed down.

David Boulton: Doesn’t that same exact argument apply to the fuzziness between sounds and letters?

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely it does.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#CodeAmbiguity

Power of English

Dr. Thomas Cable: You said that the reason you think English has become so powerful is because it allows ambiguity. The reason English has become as powerful as it is is because of Donald Rumsfeld and his predecessors.

David Boulton: The language imperialists?

Dr. Thomas Cable: Right. We rule the world and before us the Brits did, so that’s why English is as powerful as it is. Now, to be more nuanced about it, I think that ambiguity does allow English to do some things that French, for example, doesn’t. I’m thinking now about, oh, the receptivity to new words which the French are always on their guard about. So, if you look at a bilingual English and French dictionary, the English dictionary will be — if you have them in two volumes, will be half again as large as the French dictionary. Now, that’s good. In the colonies, new words came in in a way that they were not allowed in French. So, I’m sort of contradicting myself. I’m no expert, certainly, on this. But it does seem that the French were successful in repelling these intruders, whereas English was more welcome.

Certainly at the lexical level, we’ve got a lot of ambiguity. You were, I’m sure, thinking of other kinds of ambiguity as well. But yes, the ambiguity in spelling probably does allow for more creativity.

Thomas Cable, Professor of English, University of Texas-Austin, Author of A History of the English Language. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cable.htm#ThePowerofEnglish

All but Fated by How Well They Learn an Archaic Technology

David Boulton: Right. One of the things that gets me though, is that what we’re saying in effect is that the majority of our children, to some degree, are having their lives all but fated by how well they learn to interface with an archaic technology.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Well, by archaic technology, if you mean lousy teaching…

David Boulton: No, I mean by the code itself.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Well, I see what you mean. We’re not going to change the code, I’m sure.

David Boulton: Whoa, whoa, whoa…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yeah.

David Boulton: I agree that we’re not going to change the code. I’ve been a student of the hundreds of years of many attempts to change it.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Right.

David Boulton: But though we haven’t been able to change it, I think that there’s something to be gained by trying to understand it.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Absolutely.

David Boulton: How much of this problem is connected to the ambiguity that’s pent up in this code and where it came from.

Dr. Reid Lyon: There are scholars as you know who study this up the wazoo and know how the Latin and Greek influences and other influences effected …

David Boulton: The collision between two different language systems…

Dr. Reid Lyon: Right.

David Boulton: That resulted in this great ambiguity.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Right. But we can look at very transparent languages like Spanish and you’ll probably still see a very limited number of proficient kids, all things being equally matched on background and environment and all of that. In other words, you do see similar difficulties even in transparent languages. And it is referring…

David Boulton: Do you have studies on that you can send me?

Dr. Reid Lyon: Sure.

David Boulton: Okay.

Dr. Reid Lyon: In other words…

David Boulton: And indexed against how much time and instruction has gone in?

Dr. Reid Lyon: Well, I don’t know if we’ve done it that well.

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#fatedarchaic

Thinking Bent Around the Code

David Boulton: And, with respect to the general perception, the way that we think about reading, how much, when you think about our whole language strategies or phonics strategies, how much of the time, effort, cost and all of our thinking about all of this is bent around the code? Is bent around the internal structure of the ambiguities in the code.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Well, all the phonics arguments are certainly tied to that. And so much of the argument against teaching phonics is really an argument that the system is too complex to learn through any kind of systematic, explicit teaching, therefore, we should just expose kids to it and they’re brains will figure it out.

David Boulton: Which clearly does not work.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Which clearly doesn’t work. But given that you understand how complex the code it, you can at least appreciate why somebody might make such an argument.

David Boulton: Right, but when you look at the arguments for phonics in the way that we’re doing it… I mean, people like Venezky have, run powerful computer models and developed a kind of pattern map to show the structural units of morphemes and phonemes and how they’re distributed across our language system and so we have this very complex way of thinking about all of this on the other side of it.

But when we look at it from the perspective of a child coming up into it, how do we meet them step-by-step-by-step through the confusions in a way that’s keeping it consciously meaningful while their in the exercise of unconsciously automating the code processing required for it?

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: In a way, you partly answered your own question. It’s doing those two things simultaneously. It’s introducing them initially to those simplest aspects of the code and increasingly complex aspects of the code while you keep the emphasis on meaning, while you keep the kids focused on what the benefit of this is.

Those people who allow themselves to say, ‘Well, we have good statistics that says teaching phonics gives kids a benefit, therefore, we should teach phonics.’ They often go so far with it as, therefore, we should only teach phonics. Well, that’s not at all that the research says.

A typical study done on phonics instruction doesn’t look at phonics all by itself versus something else. It looks at phonics embedded in a system of reading instruction that does some of what you’re talking about: it focuses the kids on the meaning, it focuses the kids on the notion that this has some social use in their lives. So that what the youngster is getting is, yes, phonics instruction, but it’s phonics instruction in the context of these other things – writing stories and letters to each other, sharing books with each other, talking about the stories and making sense of them and talking about them. It isn’t that for the next two years we’re going to just work on letters and sounds and everything is wonderful.

David Boulton: Pound out these reflexes as if these reflexes are going to form in the vacuum of any interest in what’s going on.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: But I’m afraid that what happens with some of the folks that fight so hard for phonics is that they fight so hard for it that they lose sight of some of the other pieces. And of course, then that makes other people fight back even harder and vice versa. In fact, I think the argument itself does damage. As soon as certain people hear that you’re pushing explicit phonics, and I do push explicit phonics as it clearly gives kids a benefit, as soon as you do that, however, there’s immediately a counter-fear by certain educators that that’s all you’re going to do. And so, oh my goodness!

Timothy Shanahan, President-Elect, International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#ThinkingBentAroundtheCode

Phonics is a Code Patch

David Boulton: My sense is that phonics is a code patch.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Yeah.

David Boulton: Phonics developed in the 1600’s when after the printing press started to kick up a rise in who could be literate, teachers found out that kids couldn’t read even though they knew the letter names and they said we’ve got a problem. And this thing evolved over time to be this kind of bridge to make up for these confusions that had gotten into the code.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Certainly that’s a big piece of it. Also, there was all of a sudden an economic benefit to expanding the franchise, to letting more people in on it.

David Boulton: Sure. It became socially important to have more people reading and they weren’t reading because of the confusions that had crept into the writing system and phonics was one approach to dealing with it.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Exactly.

David Boulton: Then the whole language comes up in the 1780’s when people are saying these kids are being mindlessly, rote, mechanically drilled through these phonics exercises and they’re burning out – it’s not working. And so this oscillation is going on.

Timothy Shanahan, President-Elect, International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#PhonicsisaCodePatch

Taking the Code for Granted

David Boulton: But it seems to me that all of these things take the code for granted. As if the code is this unchangeable thing – let’s not even think about it. In a conversation with Reid Lyon, I said, “What we’re saying in effect is that the majority of our children, to some degree, are having their lives all but fated by how well they learn to interface with an archaic technology.”

And he said, “Well, by archaic technology, if you mean lousy teaching.”

And I said, “No, I mean the code itself.”

And he said, “Well, we’re not going to change that, I’m sure.”

Then Dick Venezky and I had a fantastic exchange for an hour and a half or so in Washington and in the course of it basically what we came to was that there was this systemic rationality that could explain the code variations, or the majority of them.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Yes. If you get to the syllable level depending on which set of words and which computer program you can get between about a ninety to ninety-seven percent consistency.

David Boulton: Right. But now we go back to the five year old child in school.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: (Laughing) That isn’t a computer.

David Boulton: That isn’t a computer, that doesn’t have this adult knowledge looking down on it. There’s a picture of Dick on his website on the peak of a mountain looking down on everything.I said that’s a perfect image of your relation to this code. But the kids are underwater.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Right.

David Boulton: What I am saying, that seems really important to me, is that there’s stuff going on in that code that we’ve kind of shut off paying attention to and wrapped our whole approach to teaching and thinking about reading around accepting. I think we’ve got to open it up and blow it up and see it better.

I just see how many hoops we’re forcing these kids around because we won’t look hard at the code. There’s no question that all of the things we’ve been talking wouldn’t be as difficult if the code wasn’t so radically confusing.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Well, we have these odd things. I know one that Dick Venezky taught me about was the spelling of the word of which you can track back to one scribe who made a mistake and we happened to use his text. Of was never spelled that way before that error. The spelling of the /V/ sound doesn’t appear as ‘F’ in any other word in the English language. It was shear accident and we can trace historically the accident, and yet we still spell of as o-f. And we give kids no sense of how to deal with that little problem.

There certainly have been attempts over time, as I guess you know, to give kids a simplified code to learn from.

David Boulton: ITA’s (International Teaching Alphabet), simplified spelling approaches and so forth.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Both in English and in other languages, yeah.

David Boulton: Yes, from Ben Franklin and Noah Webster to Melvile Dewey. I don’t know if you’re aware of Theodore Roosevelt’s role in all of this. He really messed everything up by trying to institute by presidential order spelling reforms that created an enormous backlash to the idea of touching the orthography.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Webster tried it with the dictionary; people have tried it with their teaching systems.

David Boulton: I think it brought Charles Hockett, the great linguist before Chomsky to say that ‘It’s easier for people to change their religions than their writing systems.’

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: It seems to be. There was Robert McCormick here in Chicago changing the spellings in the newspapers thinking that was going to fix it. But the spelling system has been pretty impervious to those attempts with the exception of Webster who actually made a little headway.

David Boulton: Fifty changed spellings, I think, or something like that.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: He certainly came up with some American English spellings that differ from the English-English spellings. But beyond that I don’t think people have made much headway.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#TakingtheCodeforGranted