Curriculum

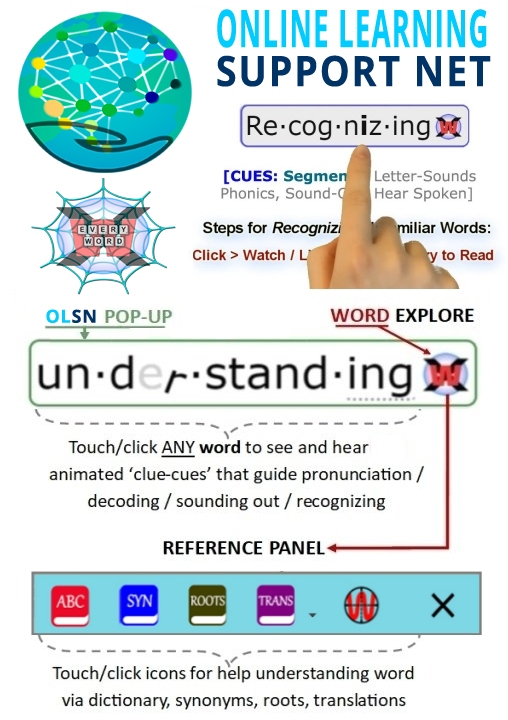

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Curriculum Depends on Fluent Reading

The functions of reading are many. At the fundamental level, the level I think everybody understands, reading is a critical academic task. It’s critical not only in the sense that Language Arts is a core component of the curriculum for elementary school children, but also in the sense that every area of the curriculum starting in elementary school depends on fluent reading.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#ReadingImportant

Reading Undergirds Most Curriculum

Reading is the gateway skill. It leads to all sorts of success, both academically and in life. It is the skill that undergirds most of the curriculum, and if children aren’t learning that skill by the end of third grade, they are in desperate trouble. For kids with learning disabilities it’s a double whammy. You know, seventy to eighty percent of students with learning disabilities have their main problem in the area of reading, with reading based learning disabilities.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#ReadingistheGatewaySkill

We Need Curriculum Solutions

We need curriculum solutions so that fewer children experience frustration and difficulty during the task of learning to read. We need to change the context of schooling so that the child who’s struggling in reading in third grade can have that problem addressed in a way that isn’t stigmatizing to the child and doesn’t generate the sense of shame. We need in some way to break out of the lock-step nature of elementary education so that if you don’t have what the other children have in first grade for some reason you are forever doomed and will never get the opportunities to pick up that information.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#Shame

Core, Supplemental and Interventional Curricula

Well, there are some things that are rather traditional and rather predictable in terms of getting schools to scale up to make this kind of difference. Obviously, you need a curriculum. You need a way of codifying the activities that the society and research deems as critical for kids to be proficient in a language system, in a writing system. So, you need tools.

Teachers need to have a curriculum. The assumption is that the curriculum is valid, it’s reliable, it’s been tested; it has all the critical elements that are associated with this conceit call the alphabetic writing system, and it’s based on research. So, there are a lot of things that schools already have in place that we would continue to argue that they ought to have in place — effective research based curriculum. So, that’s one, the curriculum piece.

Now, the question is: Do we have the right curriculum? Is it a curriculum that the public would argue is the best intervention possible? Is it tested? Is it trustworthy? I think right now the answer is no, we don’t because we don’t have the resources, at least up to this point, we don’t have the resources to really test, in a research satisfying way, experimental control group way, curricula that allows us to say, ‘Yes, if you pit curriculum A against curriculum B, we have sufficient evidence to suggest that curriculum A gives you the greatest impact for your investment because it gets kids to the kind of reading achievement outcomes you want.’

We’re getting there. We still have a lot of work to do. We have a handful of programs that have some empirical evidence that suggests that if you implement the program kids will benefit from the implementation, assuming the implementation has a high level of fidelity. So, that’s one big piece, getting the curriculum.

And there’s not one curriculum that fits all. So, that’s one of the problems. We need multiple types of curricula. We need a core curricula for most of the kids, assuming that you have a normal distribution of aptitude and performance. The architecture is such that it tries to cover a lot of stuff in a short period of time, so it’s horizontal. It’s going to cover a wide range of things but it’s not going to go very deep. In addition to the core curriculum, we need supplemental curriculum that will supplement the holes that you’re going to find in the core curriculum.

For example, if we assert that alphabetic insight is critical to reading, the phonics piece, then not all curricula will have the same amount of intensity and explicitness as they should around teaching phonics. We may want to adopt supplemental curriculum to enhance the core curriculum. So, that’s two pieces of the curriculum puzzle: a core curriculum and a supplemental curriculum.

Finally, you’re going to need a curriculum that’s very different in architecture for the kids who are in the bottom twenty, twenty-five percent, because the way they manage information is very different from the kids who can benefit from the core. That kind of curriculum we refer to as an intervention curriculum, because the architecture is very different. The architecture should be more careful in how it thinks about the examples that are used, how it juxtaposes examples, the amount of scaffolding and teacher-wording that’s provided, the amount of practice, how much practice is given at any given point in time, how much scaffolding is providing, how much rehearsal, how much fluency is built in.

Edward Kame’enui, Past-Commissioner for Special Education Research where he lead the National Center for Special Education Research

under the Institute of Education Sciences. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/kameenui.htm#CoreSupplementalCurricula

Unfolding Ambiguity through the Curriculum

David Boulton: The orthographic reform folks have mapped out 1,100 combinations between letters and sounds, 300 or so in common use. 300 combinations in the ways letters can map to sounds. 300 ways that we can spell forty-four sounds with twenty-six letters! It’s a pretty amazingly messy system.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Well, in a way that’s why in teaching children to read giving them constrained sets is very important. So that if you look at the curriculum of children in kindergarten, first and second grade, with certain good basal programs they only have children having to interact with only some of these mappings and that builds for the next layer.

Anne Cunningham, Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#UnfoldingAmbiguity

Educational Curriculum and Psychological Dimensions of Learning

David Boulton: The orthographic reform folks have mapped out 1,100 combinations between letters and sounds, 300 or so in common use. 300 combinations in the ways letters can map to sounds. 300 ways that we can spell forty-four sounds with twenty-six letters! It’s a pretty amazingly messy system.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Well, in a way that’s why in teaching children to read giving them constrained sets is very important. So that if you look at the curriculum of children in kindergarten, first and second grade, with certain good basal programs they only have children having to interact with only some of these mappings and that builds for the next layer.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#ShameDisruptsCognition