Downward Spiral of Shame

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing a language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem and making him feel pretty worthless. – Dr Mel Levine (COTC Interview)

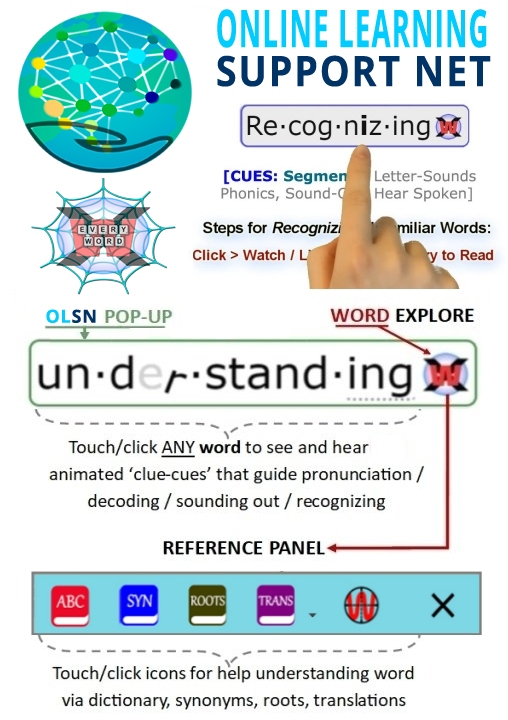

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: In one part of the series we call it the ‘Downward Spiral of Shame’.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes.

David Boulton: The moment that somebody starts to feel uncomfortable, there’s this split in the processing bandwidth necessary to do the task. And the more that they can’t do the task the more that they feel uncomfortable and the more they feel uncomfortable the less they can do the task and down and down and down.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Sure. And at the code level, the task is one that requires practice, there’s no short cut for it, and so another consequence of this is that children who are struggling don’t read; they’ll read when they’re required to read, when someone’s looking over their shoulder, but they will not read for pleasure. And there end up being vast differences in the exposure to the written language that are a function of underlying skills. The underlying skill effects motivation and the motivation effects reading for pleasure. Reading for pleasure is a source of the information that prepares you to deal with the next level of reading. So it is a cycle of failure or success that feeds on itself.

David Boulton: We have the ‘Downward Spiral of Shame’ and the ‘Matthew Effect’.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Exactly so. And reading is actually unusual in that respect. Statistically we tend to find in other areas of development something called regression to the mean. And that means that children who score the lowest on whatever assessment is being given tend to score higher next time. Likewise, at the upper end you find some regression towards average performance among those children who scored extraordinarily well. So you get kind of an ad mixture over time. With reading it’s very different, the paths are diverging. And that’s why it’s so important from an education perspective to identify the problems early and a preventive approach rather than the approach that depends on the occurrence of failure and the attempt to remediate that failure.

David Boulton: Too late.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Well, it’s not too late, but it’s extraordinarily difficult. It’s certainly expensive.

David Boulton: It’s too late in the sense that we’ve passed the point of optimal intervention.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: That’s right.

David Boulton: Not that it’s too late in a dooming sense.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#DownwardSpiral

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: One of the things that we’re very concerned with is the role of affect in all of this from a point of view of interest and attention, but also on the downside, what we call the ‘downward spiral of shame.’ What happens when the children start to feel self-conscious about reading…

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Oh, yeah! And that happens very quickly.

David Boulton: It implies a dissipation of processing resources, regardless of the emotional things that we say about it.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Forget the sublime explanations, people don’t like to do what they don’t do well. And kids are extreme human beings, you know? People like to do what they do well, and especially if it’s in front of other people.

David Boulton: But there’s no escape from reading.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Yes, I shouldn’t say people like to do what they do well — that’s not always true. But they really don’t like to do what they don’t do well.

David Boulton: We are masterful shame escape artists. We learn that very early, and all of us do it.

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: I remember when my firstborn came home from first grade one day and he said, “No, Mom, you don’t get it, because see, the girls like to read and write, but the boys don’t. The boys like to do math, but the girls don’t.” And I thought, ‘Oh, good, there’s two things I wasn’t really hoping you’d ever learn in the first semester of first grade.’

He read fine. It was just that they decided collectively the difference between girls and boys. He’s twenty now, so this was in the peak of whole language and the girls were writing books and illustrating them and binding them with yarn and stickers and all that stuff. I’m sure that the boys just said, ‘Hmm, can’t compete in this arena and not sure I want to. I’m going over here with the trucks.’

David Boulton: Which means, like you said earlier, ‘I’m going to go where I can feel good about what I’m doing and I’m going to move away from the place that makes me feel bad about myself.’

Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams: Right, and we can call them girls and us boys, and it works.

David Boulton: What’s generally animating the Children of the Code Project is our sense that a significant number of our children are confused. They’re drowning in ambiguity overwhelm, and they feel like there’s something wrong with them because of it.

Marilyn Jager Adams, Chief Scientist of Soliloquy Learning, Inc., Author of Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/adams.htm#DownwardSpiral

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: I use a term, which I’ll share more with you later, that we call the Downward Spiral of Shame that connects the affect system with the cognitive system. What happens when they start to become averse to the feeling of all of this and the downward spiral of diminishing available cognitive resources because of the dissipation of their affects.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Yes! Well said. Well said because if you are allocating so much time to shame, if you’re so concerned that the child next to you has got a thick book and you really can’t read a thick book or a chapter book yet, you can only read one of these baby books, then generally, and it’s highly adaptive I think, is that you’ll get a thick book and because of our social comparison you will pretend that you are reading that book to keep up with your peers. But the result of that is that you don’t get the practice and the shame prevents you from engaging even more.

David Boulton: And what you are practicing is a self deception, self and other deception, and what you’re learning is that you’re mind doesn’t work that well and that there’s something wrong with you.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Yes. Exactly.

David Boulton: To some degree a great deal of our children are learning to be ashamed of their mind because of this whole reading thing.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: And you know it happens so early. That’s the crime. It just happens, you can see it in mid-first grade. Little six and seven year olds are already feeling that ‘I’m not a good reader’. Well to me that’s an indictment on our educational system that we haven’t protected them enough and we’ve compared them to each other so much, so quickly that many children don’t even have an opportunity or a chance to get into the cycle. And so we have to do a far better job of not making these differences between our children so visible that they enter into this cycle prematurely. And there are ways to mediate that.

David Boulton: Right, we can also contextualize this; some people are tall, some people are short, and no animal on the planet ever read before. Humans have only been doing it for a little while, everybody struggles, it’s not a problem that you’re struggling. We can create a different kind of buffer space for the emotional processes that are concurring with the cognitive processes during this struggle.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Yes. That’s right.

David Boulton: And we’ve got to do that. That’s what Children of the Code is about, what we’re doing here.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: And it’s not to say that we’re going to, what some philosophies have done and what some teaching practices have, which is to make everyone feel good and you’re going to be fine and you can learn to read. We’re actually going to provide the instruction but at the same time create it in an environment that doesn’t allow for that high level of social comparison.

David Boulton: We are not talking about an artificial self esteem boost and compensation. We’re talking about being successful at the task by reducing the emotional negative feedback loop that’s concurring with the cognitive struggle.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Right. Yes. Exactly.

David Boulton: One of the things that’s implicit in the Matthew Effect, that you co-wrote about, is that how quickly children take to this, how quickly it catches for them and they get up into reading, so that they’re brain isn’t busy just doing the processing and they’re free to go on and appreciate what they’re reading and enjoy it enough to continue to have the affect interest excitement enjoyment lifting them into it…

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Uh-huh.

David Boulton: That if that doesn’t happen they won’t learn to process efficiently enough to read well enough to progress in the development of comprehension and fluency. It’s almost kind of like launching a spaceship into orbit. There’s this narrow little window that if they don’t get through it…

Dr. Anne Cunningham: That’s a great analogy. Yes.

David Boulton: If they’re too late getting into it then the whole thing starts to spiral negatively and starts working against they’re developing ability to read it and it requires more and more and more from them to break through.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Yes. Getting an airplane off the ground is an excellent analogy for what we have to do in the beginning stages of reading acquisition. And it does require an inordinate effort and focus on helping children to break the code and understanding these letter sound patterns and fragmenting and putting them together rapidly so those words become automatized.

In our study what we found was that children who made this break through, who broke the code early on in first grade, not only became better readers in high school, which is what we’d predict, but they engaged in print more. So one of the phenomenal findings of this particular study was that ten years later we could see that those children who broke the code early on began this Matthew Effect, this cycle of engaging in print and because they engaged and were successful in it they enjoyed it and because they enjoyed it they had positive affect and so presumably they practice it more and more. Because they practice it more and more their vocabulary grew, their level of verbal intelligence increased and so when they came upon some complex ideas or complex words, vocabulary items they may not have known, they had the cognitive space to think about, well what does that word mean and then attach it to a similar word so that they can then build their lexicon in a way that allows them to progress through out time.

And so not only do we see that they’re better readers, but that they engage in it more. And that’s what we want to promote because what we see in the Matthew Effects is everyone benefits. So that even the relatively poor reader, the child or student whose comprehension is not as good as the student sitting next to them can still grow and develop in their reading ability, but also their verbal intelligence just by staying with it and just by engaging in print on a daily basis.

Anne Cunningham, Director of the Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#DownwardSpiralofShame

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: That’s great. This is what we’ve been calling the downward spiral that happens in reading, a variation on your compass. The more shame that they’re experiencing in the overall learning to read process, the more that this is going on, the more that it’s interrupting the possibility of a good experience of reading, the more that it’s triggering shame, the more that this thing starts to work against itself.

Dr. Donald Nathanson: … as you go from a momentary, a scene of shame to the assembly of multiple scenes of shame occurring during the process of reading, then you have a buildup in the individual that we call script formation. It’s no longer a matter of just the affect shame pulling us with a new spotlight to what we can’t understand. It’s more evidence that we are poor understanders, that we are poor readers. (One of the things that can happen a great many times as we start to read and experience this painful shame.)

If a great many times that we’re reading the ambiguity triggers a moment of shame and we begin to associate reading with the pain of shame, then wouldn’t we be stupid to keep reading? What happens is that the child says I can’t read or I don’t want to do this or you can’t make me do this or reacts in a number of ways that frustrate the intent of the teacher.

This business of being unable to decipher what’s on the printed page has huge consequences for a child’s self esteem. That is the child’s general concept of who he or she is has huge consequences for how we see ourselves relative to our peers and forces us to defend against this bad feeling in a number of ways that I call the COMPASS of SHAME.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#DownwardSpiralShame

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: One of the most powerful concepts in the emerging emotional science of ‘affects’, is called the “Compass of Shame.” Or, what we’ve called in this series relative to reading, the Downward Spiral of Shame. And basically what it points to is that children, like all of us, tend to move away from what brings about shame. Moving away from print is almost second order to moving away from feeling shame….

Dr. Reid Lyon: Right.

David Boulton: Which is associated with trying to process this code.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Absolutely. The most visible thing our kids do throughout their early years is read. Reading is the most frequent and visible behavior visible to peers as kids enter school.

David Boulton: Visible because there’s a structure to it where we can see them struggling.

Dr. Reid Lyon: Yes, absolutely. Typically, from first through third grades there is a lot of oral reading, and there are interactions where the kids are expected to read out loud, orally or in round robin. When kids are hesitant, disfluent, inaccurate, slow and labored in reading, that is very visible to their peers and remember the peers, the other kids, again look at reading as a proxy for intelligence. It doesn’t matter if this kid is already a genius and can do algebra in the second grade, reading produces particular perceptions. Better said, lousy reading produces a perception of stupidity and dumbness to peers and clearly to the youngster who is struggling. That is the shame. There are very visible differences between kids who are doing well with print and youngsters who are struggling with print. They feel like they’re failures; they tell us that. (More “shame stories”)

One of the things that is both great but also sad, is that we have had the opportunity in my job working with all of our scientists at all of our sites to follow kids from before they enter school until, in many cases, they’re now twenty-three. And what is wonderful about that is we can walk through life with folks who are going to become very good readers. Sadly, we also walk through life with kids, adolescents and then adults who never learn how to read. And sadly, when we talk with these kids, adolescents and adults who’ve had a tough time with the shame of not learning to read, we find it is further exacerbated by the fact that they can’t compete occupationally and vocationally; they don’t do well in school, clearly the adolescents show us a level of pain that this society doesn’t even see. Most of society takes this for granted, but all of this begins to build up together and keep kids further behind.

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#ShameAvoidance

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: All of these dimensions are critical. We’re looking at the family context, the social context, very particularly at the emotional affective context as well as the cognitive processing challenge.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s at the very — that’s at the heart.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s the heart and soul of it. Because you can teach a person to read, and you can do all the things, but if they’ve had that hurt and that pain and that blow to their self-esteem, that’s the most difficult. We have no medicine for that.

David Boulton: Yes. And it’s not just a bad feeling they’re having; it’s fundamentally processing-level debilitating, draining of the efficiency that’s necessary to process the thing that could make them feel better. It works in a downward spiral.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s right.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University, Author of Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#SlowReaders

Downward Spiral of Shame

David Boulton: One of the things we’re interested in that connects here is shame. In particular, what’s happening, not just at the level where we say, ‘I feel ashamed of myself,’ but before that, preconsciously before that. In the admix of affect that’s powering and directing cognition when a child starts to go into shame, what’s happening to their cognitive processing bandwidth? Our sense is there’s this downward spiral that’s starting to kick in as the child starts to feel shame and the shame itself starts to become more and more occupying of attention and …

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Right.

David Boulton: Diminishing the cognitive bandwidth available for processing what they’re trying to do.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: It’s a great point, and it’s a wonderful thing to study. To some extent it is being studied but it’s a wonderful thing to try to develop a deeper understanding of. Let me just say that there is this sort of intuition that all of the change that occurs in these learning contexts is positive. That if I add emotion I learn better, right? Not right, that’s not correct.

Let me cite a simple example. If I learn under conditions of incredibly high stress, I’m extremely efficient, immediately reactive to the situation at hand, but I’m not learning worth a darn. Obviously, if I go into a period of depression and I come out of it, I can’t remember a darn thing that happened.

In an experiment, if I put an electrode in the brain of a rat or a mouse and I stimulate it each time it has an experience, a particular form of experience, so as to create a condition that would be just like very powerful activation of the brain systems that contribute to depression, what happens is that I generate an incredibly big positive exaggeration of that stimulus. It grows in the brain like a monster and everything else is degraded. So here I’m growing something that you could say is like a great fear or a great obsession, and its power in the brain is growing and growing. Everything else is degraded. So there is a negative side, a dark side to what’s happening as well. So neuromodulatory systems are not just contributing positive change.

I’ll give you another simple example. It was known since Pavlov, that if I follow a stimulus with a reward, first the bell then the meat, the dog salivates. If I ring the bell and the dog salivates, that’s called classical, or Pavlovian conditioning. Well, let’s flip it around. Let’s give the meat then the bell. What happens? The answer is a peculiar form of unlearning. What happens is that now, if I flip them around, and now I have the bell and then the meat, the dog can’t learn the relationship. I have a negative effect that is occurring.

When I look in the brain of a rat that has the same experience, I see a positive change occur when the bell precedes the meat, signaled by the release of this powerful neuromodulator. When I reverse them I see exactly the opposite. The ability of the bell to excite the brain is erased. I actually see a negative plastic consequence. So we think of this as being positive. It’s not all positive – we think of learning as positive, but it’s not all positive.

Another way to think about it is learning is selective. It’s not just that you learn everything all the time – it’s selective. It’s a selective process. Once a brain scientist, Herbert Jaspers, who is a great scientist at the Research Institute in McGill in Montreal, (I might say he told me this when he was about 90 years old) said, “Never forget that when you’re trying to get across town, it’s not just a matter of what bus you get on, it’s all those busses that go by that you don’t get on.” He said it’s being able to sort out what’s important in a complex array of things that are happening and arriving in your brain that you have to make distinctions about. The brain processes that govern the development of our behaviors are selective. Some things they operate on positively, some things they’re suppressing and they’re operating on negatively.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#TheEffectofAffectonCognitiveProcessing