Memory

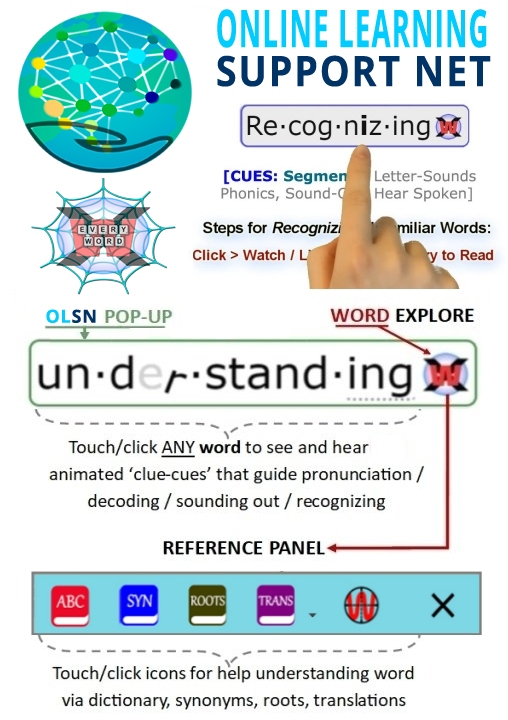

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Assembling and Holding in Memory

The problem is not only disambiguating the letter-sound relationships, they are very much contextualized, but there’s significant overhead associated with disambiguating the meaning of the words. And that process involves assembling and holding in memory not only information that came from outside of the written text, but information in the prior sentences and paragraphs that have been read. And you find these two problems coming together and creating special difficulty for kids.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#UnnaturalDisambiguation

Time and Working Memory

The longer it takes you to read something, the more memory and more attention it’s going to require. We’ve got kids who, on the struggling side, hesitate, mispronounce – it takes them so long to read a passage they can’t even remember what the heck they read after a sentence, much less the passage. Yes, the capacity that goes into this print level work is far too great to give room for comprehension for relating new to known, there’s no doubt about it. The majority of our kids who have a tough time – they are slow, they are labored in their reading, they are hitting the wall on a lot of these print skills.

Zvia Breznitz, Director, Laboratory for Neurocognitive Research, University of Haifa. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/breznitz.htm#TimeandWorkingmemory

Processing Drain of Inefficient Reflexes

And it’s an astounding neurological achievement to be able to process all of that information, to simultaneously consider multiple sources of information, both code related, phonological and semantic, and to keep all that in memory and produce something that’s understandable to oneself or somebody else.

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#processingdrain

Astounding Neurological Achievement

And it’s an astounding neurological achievement to be able to process all of that information, to simultaneously consider multiple sources of information, both code related, phonological and semantic, and to keep all that in memory and produce something that’s understandable to oneself or somebody else.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#AstoundingNeurologicalAchievement

Ambiguity Processing Takes Time

But the truth is that reading is one of the more complicated of the higher cognitive functions using attention and rate-of-processing and sequencing and memory and the linguistic systems and the visual system and it’s having to coordinate this dance that’s going on. And the more complicated the translation from the orthography to the phonology is to a particular language, the more complicated this processing dance has to be within the brain. I think the search for a single cause, for example, or single basis for reading in the brain, a single spot that’s going to be activated for reading or a single cause why a child may have difficulty learning to read is both fruitless and not likely to ultimately be correct because it’s too much of a dance and it requires too many moving parts.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#AmbiguityProcessingTakesTime

Faults Underlying Defective Language Representation can Limit Operations of Memory

Well, in some instances, in some classes of problems that children have there are very strong commonalities, that is to say you could look at it statistically. Every child that has a language impairment does not have it for identical reasons. In the surface detail, it will have many different expressions. On the other hand, the faults that underlie a defective language representation in the brain that limits operations of memory and thinking and usage of language have much in common in the great majority of children that have such an impairment. So there are fundamental aspects that are seen over and over again in children that have such impairments. And those can be attacked and be addressed.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#NeurologicalProgressionandCorrection

Neuroplasticity and Sound Representations

In other words, in terms of the memory system, if the information flowing into the brain is represented in a non-salient way, it means that the capacity of the brain to encode and record it is degraded. If I refine it, if I strengthen it, I strengthen the capacity of the brain to record it reliably as a memory. So there are whole series of downstream, important, crucial consequences that occur from having a clear signal in.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#NeuroplasticityandSoundRepresentations

Memory and the Code

Dr. Richard Venezky: What’s got to go on during reading is not only getting the letters in and getting either sounds attached to them, if it’s not something that’s visually familiar, or accessing visual memory or some other encoded memory that doesn’t require sound and retrieving then the meaning. And if you’re reading orally retrieving the pronunciation…

David Boulton: Are you suggesting that some children learn to read by bypassing a virtual pronunciation?

Dr. Richard Venezky: No. But let’s begin with a fourth grader.

David Boulton: Four years down the road of learning to read

Dr. Richard Venezky: Yes, and then come back to the beginning. Let’s take a fourth grader. A fourth grader reading silently is probably going to recognize 90% of the words in a text from just the printed form. He’s not going to decode them, not going to pronounce anything whether it’s sub-vocal, vocal or anything else. A fourth grader is going to read a fourth grade text basically silently.

David Boulton: When you say silently you’re saying that they are not having a virtually heard experience?

Dr. Richard Venezky: Right. Exactly.

David Boulton: So doesn’t that vary across the spectrum of different processing styles? I mean I still hear words when I read, in a virtual sense.

Dr. Richard Venezky: Be careful with introspection – it can be misleading.

David Boulton: I don’t mean to generalize from there. I’m simply saying that I’m an exception myself and most of the people I talk to are on a spectrum.

Dr. Richard Venezky: Virtual hearing could result from an abstracted sound stream that is retrieved AFTER the word is recognized, not before. At issue here is how the printed word on a page is connected to an appropriate area of the brain where information about that word is stored. Is that connection made directly from the visual pattern or are the letters first translated to sound and then the sound used to search listening memory?

One piece of evidence on this issue is that fourth grade is roughly the point where reading speed for silent reading overtakes that for oral reading. And that’s one clue that readers are not articulating the words because if they were, even in a sub-vocal way, it would be difficult to be reading much faster than one’s speaking rate.

Richard Venezky, Past Unidel Professor of Educational Studies and Professor of Computer and Information Sciences, and Linguistics at the University of Delaware. He is the author of The American Way of Spelling: The Structure and Origins of American English Orthography. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/venezky.htm#TheCode

Alphabet Promotes Wide Literacy and Democracy

It’s certainly true that the alphabet is easier to learn than any other forms of writing. But again, I think that what somebody like Eric Havelok would argue, and what many people who’ve looked at the transformation from oral to literate cultures would discuss would also be the ways in which the coming of literacy has a relationship to what has gone before.

In other words, if you have an oral tradition that is founded on the idea of memorization and that will create certain kinds of repetitive mnemonics, or certain kinds of devices for enabling memory within the way in which knowledge is transmitted, whether those are verses that repeat or tales that have a narrative structure. This narrative is a very assumable form for us for knowledge. What those forms are is also transformed by the coming of writing systems because writing allows static seeming abstractions to be fixed in a semi-permanent way so that we don’t have to rely upon many things that are almost physical, physiological somatic properties. Rhythm is a very somatic property. Our bodies feel rhythm. If you perform a poem that has a certain rhythm you will be able to remember when it says something else, because there is a break in the way it goes.

You can see how that really is a memoryfunction.But, if I’m going to make a list and put it on the wall, I don’t need the somatic properties of the memory system. So, I do think that these transformations are significant in the way in which, not only literacy functions, but in the way the structure of knowledge is presented, and what constitutes knowledge has come to be understood by a culture. There are people who would argue, I think, that the way in which we read from left to right in Western culture is something that has to do with brain function; whether it is determined by brain function or whether it actually ends up patterning our ways of processing knowledge, because of the way that we are educated is a question. Probably the two things work together. It wasn’t always the case.

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#AlphabetPromotesWideLiteracy

Memory

Well, it turns out that as far as memory is concerned, we’ve got lots of different kinds of memories. I mean, there’s one kind of memory which is skill memory, you remember how to ride a bicycle. But there’s another kind of memory which is a memory of facts and dates and places and memory of narratives and memory of histories. All of those things, at least the interesting ones for us, require a language, and the more elaborate ones require a written language.

John Searle, Mills Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Language at University of California-Berkeley. 2004 National Humanities Medal for shaping modern thought about the nature of the human mind. Author of Mind: A Brief Introduction to the Fundamentals of Philosophy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/searle.htm#Memory

Episodic and Procedural Memory

For me, one of the things I think is really exciting about languages is this aspect of how it reflexively changes the way we think. I think that’s one of the most amazing things about being a human being.

When people talk about memory they usually talk about two kinds of memory. Episodic memory, remembering a particular thing that happened, a sort of one off event in your past; and then something called procedural memory, the kind of memory that’s involved in skill learning.

The problem with one-off memory is that there’s so many one-off events, how do you find them again in your memory? The problem with procedural memory is you’ve got to be in the same situation. I know how to ride a bike when you put me on a bike, but if you ask me to tell you exactly which leg I put on first, how do I start out, how do I stay up, I couldn’t tell you because it’s, in a sense, imbedded in its context.

Language is unique in the following sense: that it uses a procedural memory system. Most of what I say is a skill. Most of my production of the sounds, the processing of the syntax of it, the construction of the sentence, is a skill that I don’t even have to think of. It’s like riding a bicycle. I don’t even have a clue of how I do it.

On the other hand I can use this procedural memory system because of the symbols that it contains, the meanings and the web of meanings that it has access to, that are also relatively automatic, to access this huge history of my episodes of life so that in one sense it’s using one kind of memory to organize the other kind of memory in a way that other species won’t have access to without this.

The result is we can construct narratives in which we link together these millions and millions of episodes in our life in which you can ask me what happened last month on a particular day and if I can think through the days of the week and the things I was doing when, I can slowly zero in on exactly what that episodic memory is and maybe even relive it in some sense.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#EpisodicandProceduralMemory

Need for Cultural Memory

We also have the need for memory, for cultural memory. I think, again, the transformation to a history sensitive, record-keeping culture is significant in this period as well. It’s one of the things that scripture provides, a sense of human cultural memory and myths and tales. The tales of Gilgamesh, other writings from the ancient Middle East, the Book of the Dead from Egypt, these are ancient scripts that, again, are preserved through writing, and passed on. So that’s quite early. It’s 1700 B.C. when we begin to see the alphabet come into being.

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#TheEmergenceofWritingintheWest

Verbal, Self-Reflexive, Volitional Memory Recall

Clearly, it changes everything about what being a human being is. Again, I use the phrase, the symbolic species, quite literally, to argue that symbols have literally changed the kind of biological organism we are. Not just in evolution but in day-to-day life. I think we operate fundamentally different at a cognitive level because of this.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#VerbalSelf-ReflexiveVolitionalMemoryRecall

Alphabet and Explosion of Greek Civilization

The other thing is that when the Greeks start to look at hieroglyphics, that’s the beginning of this kind of projection of otherness onto the hieroglyphics in a sense that, oh, look at these signs. These are amazing. What is that culture that has this amazing capability? They attribute powers to these writing systems that the writing systems don’t necessarily have and they also invent a sense of history.

It’s that historicist’s sensibility, I think, that becomes so bound up with writing – that if you have writing, then you have the capability for memory and transmission. If you have memory and transmission then oral culture can do something else. You begin to have these separations and specializations of activity. So rather than having oral cultures that have to do everything, in other words perform and record and transmit and become the sort of the site for production of community and identity at the level of person, and sort of state and nation and so forth as we move forward in time, you have the sense that the writing, the written record, does some of that work. The written record becomes a kind of point outside of present experience that is always bound with the past.

We always think of writing as memory. Writing is always bound up with memory. And that’s why I say I think it’s a kind of early historicism. Even though you have legends before the Greeks, and you do have kinds of tales of conquest and so forth, the sense of history as a practice is something that I think we really do get from the Greeks, from Herodotus.

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#TheAlphabetandTheExplosionofGreek

Plato's Point

Then here’s this whole discussion in Plato in the Phaedrus about Thoth. This is the other great debate. Is writing an aid or a detriment to memory? Plato makes a point that actually sort of differentiates different kinds of memory. In the Phaedrus he’s talking about the fact that Thoth takes writing to Thamus, the king of Egypt, and he claimed “That the letter would make the Egyptians wiser, and give them better memories. But Thamus wasn’t convinced and he argued that the invention would, in fact, create forgetfulness because they would trust the external written characters and not remember of themselves.‘

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#GreatQuote

Socrates' Point

This is the Socrates. This is Noel Humphries’ retelling of this:

“This science, letters, will render the wisdom of the Egyptians greater and will give them a more faithful memory. It’s a remedy against the difficulty of learning and of retaining knowledge. Those who learn them will leave to those strange characters the care of recalling to them all that they should rather have confided to memory. And they will themselves preserve no actual recollection of these things. Thus, thou hast discovered not a means of memory but only of reminiscence. Thou giveth to them the means of appearing wise without really being so for they will read without the instruction of masters and think themselves wise upon many things when, in fact, they will be ignorant, and their intercourse will be insupportable.”

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#GreatQuote

Argument for Writing for Samuel Hartlib

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#GreatQuote

Alphabet and Spelling Reform

The realization that the alphabet is difficult to learn is something that’s not a recent notion, and so there have been many attempts to reform the alphabet. The forces that work against this, of course, are convention and the fact that many things have been written in alphabetic characters, and that to lose that cultural memory is something that is a serious risk if we put a new code into place.

Johanna Drucker, Professor of Media Studies and Director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. Author of The Alphabetic Labyrinth. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/drucker.htm#AlphabetandSpellingReform

Children of the Code

David Boulton: … There is a direct correlation between the orthographic depth, opaqueness or ambiguity in the letter sound relationships, and the difficulty associated with reading. For example, the relationship between the word live (long i) and live (short i), can’t be derived from the code itself, it has to be contextually disambiguated…

Dr. Christof Koch: Yes, yes.

David Boulton: …through attention to words down the road a word or two. That means that a lot more information must be buffered up in the brain and some contextual processing has to participate in the iterations that resolve the ambiguity about the letter sounds.

Dr. Christof Koch: Yes. I guess you need your short-term memory, acoustic memory to deal with that.

David Boulton: Right. So in some sense, this kind of ambiguity may be partly responsible for expanding or exercising, or pushing the limits of our abstract, memory processing.

Dr. Christof Koch: Yeah, yeah.

David Boulton: One of the main points of our series is, “we are children of this code”, just like Francis Crick’s work showed we are children of the DNA code.

Dr. Christof Koch: Yeah, yeah.

David Boulton: …our civilization and our minds, in some respects, are reflections of how this code works and what it makes possible.

Dr. Christof Koch: One thing I’ve wanted to understand better… I grew up in a German household, not actually in Germany. And of course, what you have in German — if you’ve ever read, for example, Thomas Mann, who is, of course a very high functioning human being, you will find sentences which contain 200 words, with a verb at the very, very end.

David Boulton: (Laughs).

Dr. Christof Koch: It can literally run on for two pages. I’ve always wondered if there is a correlation between the average between lengths of sentences in a language and the average short-term memory span of its users.

Could we surmise that people who grew up speaking German should have a better short-term memory because they constantly need to use it compared to English folks? I mean, typically, if you read the New York Times compared to the typical similar German paper like the Frankfurter Allgemeine, which is for roughly the same reading audience — I mean, if you just look at it, English sentences are much, much shorter.

David Boulton: Right.

Dr. Christof Koch: Again, I wonder whether anybody has correlated that, along the lines which you suggested before, to see whether this also has implications for short-term memory duration.

David Boulton: I think it would be a great thing to do. I had a conversation last week with Guy Deutscher. I don’t know if you’ve seen his book, Unfolding Language, an Evolutionary Tour of Mankind’s Greatest Invention.

Dr. Christof Koch: No.

David Boulton: He’s a linguist in Holland. Anyway, these are questions linguists haven’t got to yet, but they’re intrigued by them. And just as you were saying, the sentence structure and verb placement in the structure, and what is required in terms of memory stretching and so forth, is interesting. We are what we’re exercised to be, in a certain way, and this must be affecting our cognitive processing, if you will.

Dr. Christof Koch: Sure, oh, yeah, it must.

David Boulton: And in the case of English, what’s so interesting is, again, we have twenty-six letters making forty-four sounds in hundreds of different combinations.

Dr. Christof Koch: (Laughs) It’s a lot.

David Boulton: So, we’re talking about having to disambiguate a code at high speeds. Throughout the emergence of literacy in the western world through the Greeks and the Romans, the writing systems were phonetic, one letter, one sound. Reading was code-cued speech ‘see the letter – say the sound’ blend as you go – you’re reading. But now with the confusion caused by the collision of the Roman alphabet and the sound systems in the romance languages, there’s a different requirement for the brain to read and that’s affecting us.

Dr. Christof Koch: You know, that’s an interesting point. That’s a very good point. All right.

Christof Koch, Professor of Cognitive and Behavioral Biology, California Institute of Technology. Director, Koch Laboratory, member of the Division of Biology as well as the Division of Engineering and Applied Science. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/koch.htm#Children_of_the_Code