The Power of Shame

First reading itself and then the whole education process becomes so imbued with, stuffed with, amplified, magnified by shame that we can develop an aversion to everything that is education.

– Dr. Donald Nathanson (COTC Interview)

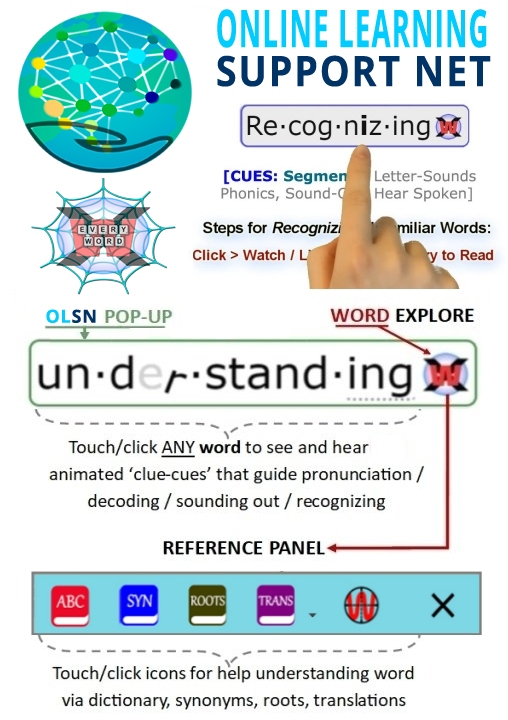

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Shame

Typically, from first through third grades there is a lot of oral reading, and there are interactions where the kids are expected to read out loud, orally or in round robin. When kids are hesitant, disfluent, inaccurate, slow and labored in reading, that is very visible to their peers and remember the peers, the other kids, again look at reading as a proxy for intelligence. It doesn’t matter if this kid is already a genius and can do algebra in the second grade, reading produces particular perceptions. Better said, lousy reading produces a perception of stupidity and dumbness to peers and clearly to the youngster who is struggling. That is the shame. There are very visible differences between kids who are doing well with print and youngsters who are struggling with print. They feel like they’re failures; they tell us that. (More “shame stories”)

One of the things that is both great but also sad, is that we have had the opportunity in my job working with all of our scientists at all of our sites to follow kids from before they enter school until, in many cases, they’re now twenty-three. And what is wonderful about that is we can walk through life with folks who are going to become very good readers. Sadly, we also walk through life with kids, adolescents and then adults who never learn how to read. And sadly, when we talk with these kids, adolescents and adults who’ve had a tough time with the shame of not learning to read, we find it is further exacerbated by the fact that they can’t compete occupationally and vocationally; they don’t do well in school, clearly the adolescents show us a level of pain that this society doesn’t even see. Most of society takes this for granted, but all of this begins to build up together and keep kids further behind.

G. Reid Lyon, Past- Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Current senior vice president for research and evaluation with Best Associates. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm#ShameAvoidance

Ripple Effects of Reading Difficulty

I do see some very interesting ripple effects when kids are not acquiring reading skills. For example, it might be that a particular child in fourth grade is having difficulty keeping pace with reading comprehension or with decoding, and because he’s having trouble with reading, he hates to read. And when he does read, he gets almost nothing out of it because he’s reading very passively. And because he’s reading very passively, he’s not able to use reading as a way of building his language abilities.

So, what oddly happens is that his language problems caused his reading problems, and his reading problems are now causing much more aggravated language problems. Those language problems, in turn, are going to make it hard for him to follow directions, communicate well with other people, and even use language inside his mind for something called ‘verbal mediation.’ Verbal mediation is the process through with which you regulate your behavior and feelings by talking to yourself. And believe it or not, a lot of kids with language problems really don’t use language as a way of regulating themselves.

They get in trouble, they get depressed, because they don’t have a voice inside that says, ‘Yeah, I could take that medicine. I could take that drug from that kid, and hey I’m a cool dude. But oh, if I take it, I could like wreck my brain, and I could get addicted and my mother will kill me if she finds out, and I could get arrested.’ And all of that comes out of language, that sort of verbal conscience that’s guiding you.

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless.

Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

Difficulties in Reading Profoundly Undermine Self-Esteem

It’s hard to separate language from the development of self- esteem, self- worth and struggling at school. Although I’ve heard many parents say you know, ‘It’s such a frustrating problem: dyslexia or language learning problems because everyone looks at your child and thinks they’re fine. If they just worked a little harder they would be just fine. And yet you can see a child literally who started off being fine begin to wither on the vine as they begin to struggle at school and lose so much of their self esteem in the process.

So, this is a major problem. Not only is it a major problem for the long term economic development of the country – which of course is why I think there’s such a huge focus on literacy – but I think it’s also a huge problem for society to recognize the tremendous toll failure in school, which usually manifests itself earliest as failure learning to read, has on the development and the maintenance of self- esteem, on the sense of self of the individuals who have had difficulty learning to talk or learning to read or learning to communicate. Even when they have become successful adults, even doing very, very well, many times if you ask them about their earlier experiences you can still see the pain of that failure – the sense of failure has never left them.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#DifficultiesinReadingProfoundlyUnder

Self-Esteem and the Affect of Shame

I think the low self-esteem, the sense of shame, is life-long. At the National Center for Learning Disabilities, we have a wonderful board of directors. We have at least two individuals on that board, both of whom have dyslexia and both of whom are former governors. They are extraordinarily accomplished individuals, both of them dyslexic. And both have talked at length about the continuing sense, not just of frustration or memories of failure, but precisely a sense of shame that is still remembered…classroom based, other children around, a teacher, not being able to do what other children seem to be able to do so easily. It stays for a lifetime.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#SelfEsteemShame

Shame Avoidance and Dependence

David Boulton: Sometimes it’s so powerful and fast and operating before those kind of rational reasons to just be an avoidance. One of the dimensions that we’re trying to bring to this is our work with emotional scientists and cognitive scientists and neuroscientists and bringing together just what is going on here. There’s no question human beings generally do not like to feel shame. We’re learn very young to become escape artists.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely.

David Boulton: We’re being put into circumstances, with this learning to read challenge, in which day after day, week after week, month after month, in some cases year after year, we’re forced to do something we’re not good at. It’s not like basketball or sewing or music or other things that are an option –you can’t avoid it. And these kids are developing a shame aversion to the feel of their own learning.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: Absolutely. And when they become adults it ends up becoming a part of the social reality of their lives. It’s not just harder to learn then, but emotionally that whole network that builds up around you makes it tougher. So if you’re that low on literacy what usually happens is you have to find somebody you can depend on. I might not want the whole world to know, but maybe my spouse knows that I am illiterate or maybe it’s one of my older kids, but nobody else does. What that does is it builds a dependency. If I were especially low on literacy and my wife knew it she would do certain things for me to take care of me and make sure that I’m okay. But what happens to the relationship when I decide this is terrible, I have to go learn literacy, I’m going to go enroll at the local library program or whatever. How much does that threaten the partner who has come to depend on my dependence?

Quite often when an adult who is really low on literacy goes off and becomes literate it leads to divorce. There are many cases documented where women are beaten or abused in various ways, either verbally or physically, certainly emotionally, because the partner who is depended on doesn’t want to give that up. The reason you’re going for literacy classes is because you want to get away from me.

Even when it’s a child who is the one who is being depended upon, the children get quite angry. It’s like mom wants to leave me or mom doesn’t love me anymore and that’s why she’s doing this. The trick is to catch this thing early enough so we don’t get to that point where there are those kinds of problems in people’s lives. That is essential.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#ShameAvoidanceDependence

Rick Lavoie "Ear" Story

I’ve heard some amazing stories from people. I was speaking not too long ago at a community college in Cape Cod, Massachusetts and this young man approached me and said, “I really want to talk to you about something. Can I set up an appointment?” He set up an appointment and came to see me a week later and he said, “I’m a student here at the community college. I have severe learning problems. I had a horrible time in elementary school and middle school and high school. It took me five years to get through high school. I finally graduated from high school.”

He wanted to tell me his story. He said, “I was born here in Cape Cod and my dad was a lobster fisherman. He was a very, very hard working guy who took his job seriously. My mom was a housewife and she took her job seriously and did real well at her job.

“It was made very clear to us as the kids in the family that it was our job to do well in school. There would be no excuses, everyone had their job to do and we were to do well in school.”

“I got into first grade and I couldn’t read. The other kids could make the books talk. They’d pick the books up and words would come out. To me it just looked like lines and circles and squiggles, I had no idea where the words were.”

He said, “I realized some seventeen years later I was diagnosed as dyslexic, but all I knew at the time was that I was a six year old kid and I wasn’t doing my job.”

“Around the middle of October the teacher began hassling me because I wasn’t able to read and by the end of October the kids were making fun of me because I couldn’t read. And I realized it wasn’t going to be too long before my mom and dad found out that I wasn’t doing my job. So I was scared. I was really scared.”

“But I was also a real resourceful kid and I looked around the room and I noticed there was another kid in the class who couldn’t read. This kid couldn’t read a lick – and yet nobody made fun of him because he couldn’t read and the teacher didn’t hassle him because he couldn’t read – because he was deaf. He wore a hearing aid, he had a hearing loss. And because he was deaf no one expected him to read on time.”

He said, “So I figured in my six year old mind the solution to my problem was to convince everyone that I was deaf. And if I could convince everyone I was deaf they’d stop hassling me about the reading. So I went on a one-man campaign to convince everyone in my life that I couldn’t hear.”

“I’d be sitting in class and the teacher would call my name and I would just ignore her until she came over and tapped me on the shoulder. What? I didn’t hear you, I didn’t hear you.”

“I trained myself not to respond to loud noises. There would be a loud noise outside of the classroom, all the kids would run to the window and I would stay at my desk working like I didn’t hear it. We’d be out at recess, the bell would ring and all the kids would come in from recess and I would stay out in the jungle gym until the principal came out and said, ‘Daniel, didn’t you hear the bell?’ No, sorry, I didn’t hear the bell.

“At home I’d be having dinner and my mom would ask me to pass the salt and I’d just ignore her until she tapped me on the shoulder. ‘Dan I asked for the salt.’ Mom, I didn’t hear you.”

“My dad would call us to come in from play and I’d stay outside until my dad finally came out there. ‘Dan, I’ve been calling you for ten minutes.’ Dad, I didn’t hear you.”

He said, “I even remember when my parents would go for an evening out, I would be watching the television and as soon as I saw the lights of the car coming down the driveway I would run over to the television set, turn up the volume as high as it would go and be standing with my ear cocked against the speaker when they came in.”

“They took me to hearing doctors and audiologists all over Cape Cod and they put a cup on my ear and they’d say, ‘Do you hear that beep?’ And I’d say no I don’t even though I did. “

“After a while I convinced everybody that I couldn’t hear and everything was fine until June.”

I said, “Well, what happened in June?”

At this point, seventeen years later, he began to shift in his seat and tug on his collar a little bit and his voice cracked a little and he said, “I’ll never forget it. My mom and dad sat me done the last day of school in June in the first grade and said ‘Dan, we’re really worried about your hearing. You don’t seem to be able to hear. We’ve taken you to hearing doctors and audiologists all over Cape Cod and nobody can figure out what it is. So we’ve made an appointment for you and you’re going to go to Boston Children’s Hospital next week and you’re going to stay there for four days and three nights and they’re going to do exploratory ear surgery and have your adenoids surgically removed.’”

And this six year old kid went through three days of surgery rather than tell his parents what he had done. Can you imagine the trauma of a six-year old child going through surgery that only he knows he didn’t need?

Rick Lavoie, Learning Disabilities Specialist, Author: How Difficult Can This Be?: The F.A.T. City Workshop & Last One Picked, First One Picked On: The Social Implications of Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lavoie.htm#EarStory

Secret Shame

David Boulton: Well, we’ve been interviewing a number of people on the adult literacy and juvenile justice sides to get a triangulation on two levels: the shame aversion and the hiding that goes on. Robert Wedgeworth at ProLiteracy described a recent adult literacy studies in which what they found to be the most striking correlation in the buying behavior of people that are challenged with respect to reading, is the extraordinary degrees they go to hide it.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Oh, absolutely.

David Boulton: It just goes to show us again how powerfully locked up this is with shame.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Oh, absolutely. To give another example — I think it would be very important for people, though, in your project to make sure that people can understand how very bright and sometimes very successful people can have this. Some of the most distinguished professors or our best students will come and ask to speak to me. This has happened so often now that my assistant knows, and she’ll lead them into my office, and they’ll look around to make sure no one can hear, close the door, and then will say, “I have to tell you something. You’re not going to believe it. And no one knows this about me.” Then I know exactly what they’re going to say, you know, what a terrible reader they are, or how slow they read, or how long it takes them. They’re filled with shame and they think they’re the only one who has this. I say, “Well, you know, I’ve seen many of your colleagues.” I don’t mention who they are. They say, “Really? I can’t believe that.” They think they’ve somehow fooled people. (More “shame stories”)

David Boulton: Yes. That’s such a powerful piece. The other thing that very few people get that’s connected to this is more at the processing level, that the more that shame accumulates the easier it is to trigger.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: That’s right.

David Boulton: And the moment that it triggers it sucks up bandwidth, that diminishes their brain’s capacity to process the code.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Well, that’s right. That’s right. That’s why it’s so critical to try to reach children really early.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Sally Shaywitz: Because it’s just an extraordinary thing, and how it affects people in every walk of life. I hope you will show some highly successful people talking about it.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University; Author: Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Phone Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#SecretShame

Emotional Dimensions

Dr. Michael Merzenich: I once asked a very prominent American, very successful individual, one of the hundred most wealthiest Americans, why, given his great individual success, he felt investing in dyslexia related research was so important? Why did he cared so much? It was clear immediately when the question was asked, why he cared so much. He still felt the pain of self-identifying as a kid as a failure and of perhaps that self-identification more than his good parents was still carried as a burden by him later in life. (More “shame stories”)

David Boulton: He clearly triumphed over it.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: He clearly triumphed over it, absolutely.

David Boulton: Whereas, you know, there are many millions who don’t turn out nearly as well.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: The prisons, you know the world of failure is full of them as we know – people who never recover their self-esteem from those early failures.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and founder of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm

Dying to Learn but Hiding in Shame

David Boulton: So, what have you got in terms of statistical correlations? Take me through some of the studies that you have done that help identify and strongly point to some of the correlations that we’re generalizing about.

Dr. Peter Leone: Okay. At least a lot of the early work that I did had to do with tracking kids as they left restrictive settings. Some of it had to do with documenting the status of service for kids in secure facilities, detention and commitment facilities. More recently I’ve taken a look at reading, for example, and have, along with some colleagues, demonstrated that in a relatively short period of time you can boost kids’ reading comprehension and their fluency, and change their attitudes about reading. By a short period, I’m talking about a six-week intensive summer school program or a supplemental program in the evenings following the end of a school day.

I’ve got a great anecdote for you. One of my colleagues, Will Drakeford, did a study at the Oak Hill Academy, which is a juvenile correctional facility operated by the District of Columbia, and located in Laurel, Maryland. It was a very small-scale study. It was what we call a single-subject research design study and he had six kids. They were sixteen and seventeen-year-olds. They had a history of special ed services and they were all reading below the tenth percentile for their age.

So, he set up a program. They were receiving services, I believe, two evenings a week from a one-to-one tutor, with a direct instruction sort of format, kind of going back and picking up the gaps in their understanding and skills related to reading instruction. After running this a couple of weeks, kids would sneak out of their cottages in the evening and come over to the school because they wanted to participate, kids who weren’t part of the study.

David Boulton: Oh, wow.

Dr. Peter Leone: So, here you have the most restrictive environment. You have kids, after the end of a four and a half, five-hour school day, going to dinner, recreation, and then having this extended time in the evening. And the word got out, “Hey, you want to learn how to read? Come to see this project that Will Drakeford has got going.” So, it was great supporting evidence that, I mean, kids are dying to be more competent. But they also do not want to let strangers or folks that they don’t trust know that they can’t read when they’re teens or young adults.

David Boulton: They’re dying to learn, and they’re overwhelmed with shame.

Dr. Peter Leone: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely.

Peter Leone, Professor of Special Education at the University of Maryland; Director of the National Center on Education, Disability, and Juvenile Justice. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/Leone.htm#DyingtoLearnbuthidinginShame

Hiding Their Illiteracy in Prison

Dr. Peter Leone: I’ve got an adult story for you. This happened a few years ago. An inmate I was interviewing in adult corrections told me this. He was a good-looking guy, developmentally disabled and he was a non-reader. In prisons, adult corrections, if you’re not competent, not able to read signs, or adequately respond to instructions, you can be really vulnerable to stuff other inmates might do to you and to having your stuff taken. So this guy is standing out in front of this trailer inside the prison and it’s where the commissary or the canteen used to be, but the prison had moved it. There was a big sign that said, “Commissary has been moved. It’s now in this other location. You will be subject to disciplinary write-up if you” — you know, “stay behind this line,” or something like that. Basically, it was now office space or something. And this guy is waiting by this window or this kind of opening that used to be part of this commissary.

He’s standing there waiting, and a correctional officer comes up to him and he says, “What are you doing here? Can’t you read?” This guy says, “Well, no, I can’t,” and the correctional officer got all upset at him because he thought the guy was being sarcastic. The guy said, “I can’t read.”

If you were to talk to him for a few minutes you would get a sense that his font of basic information was pretty limited, but he didn’t look any different than you or I. These folks that become adults who are not competent readers, they do whatever they can to pass.

David Boulton: Right.

Dr. Peter Leone: They don’t want people to know.

Peter Leone, Professor of Special Education at the University of Maryland; Director of the National Center on Education, Disability, and Juvenile Justice. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/Leone.htm#HidingTheirilliteracyinPrison

Low Literacy, Isolation and Shame

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: It is a kind of shame and they do hideout. Again, you see that participation in professional organizations and honorary societies are more linked to high literacy than low literacy. Well, that’s not surprising to anybody. But then you start to look and you see that adults who are low literacy are less likely to participate in athletic organizations. They’re less likely to participate in religious organizations. They don’t take part in as many of the social activities. They essentially get isolated.

You talked about it being an intellectual aversion, I think that’s part of it, but I think it’s even bigger than that. I think there’s a kind of a pulling back, there’s an embarrassment.

David Boulton: A shame aversion to everything that can stir up the kind of shame they want to avoid.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: You got it. It plays out in terms of I’m not going to participate in an intellectual discussion or debate, or whatever, but I’m also not going to participate in a lot of other social activities as well. So, they really are losing out on big chunks of their lives.

What it means is that we’ve put through the civil rights laws of the 1960s and we’ve done so many things to try to facilitate full participation, but literacy still is there as a barrier holding people out, even though politically the barriers have been taken down.

David Boulton: In a recent report from ProLiteracy, according to their surveys and also by American Medical Association research, they find that most of the people that can’t read go to inordinate lengths to hide it. Something like sixty percent haven’t told their spouses. One projection was that when low literate Americans walk into a grocery store or department store they are stirred with anxiety trying to make sure that they can get past the cash register without making a mistake that they can’t afford but that they can’t know they’ve made because they don’t have the skills.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: This hiding of the problem is real common. I don’t have a lot of statistics on it, but I have many personal experiences. For example, the mother who had come into one of our literacy programs – her kids were eight or nine and she was taking literacy classes because she didn’t want to hide it anymore. Her children, even at their age, didn’t know she didn’t have literacy. It was really surprising that she could hide that from them living in that household for so long. She said she always had to be on guard.

For example, she told us that, ‘When the kids come home from school I always make sure I’m busy – I’m washing, I’m ironing, I’m doing something so that if they come in and say here’s a letter from my teacher it allows me to say set it down I’ll get to it later, I don’t have time for that right now.’ She would depend upon her husband to do her reading.

In North Carolina we held a seminar on literacy for some teachers and we brought in a local business man who was low in literacy and he was willing to come in and talk to the teachers. The thing that was important was only two people in his life knew about his literacy problem: his wife and his business partner. Nobody else knew because he feared that if any of potential clients knew of the problem, he wouldn’t get contracts. He wanted this kept absolutely secret. We literally had to smuggle him onto the campus where we were working and put him in a room where we pulled the shades and had a guard at the door. (see Shame Stories)

These fears, sometimes it’s just a personal thing, that I don’t want my children to think less of me, and in other cases it really has larger meaning in terms of I don’t want to be discriminated against.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#LowLiteracyIsolationShame

Reading Exercises Intelligence

David Boulton: So, what you’re talking about, why reading is this gateway, is not as simple as it’s often made out to be, ‘when they can read they can acquire knowledge’. It’s much richer and much more detailed, which you’ve given great voice to. It’s a cognitive exercise environment of an entirely different kind that has emotional consequences, serious consequences. Have you yourself, as an add to the Matthew Effect – something like I was suggesting in the downward spiral of shame – have you given attention to or can you speak to the emotional processes that are concurring with reading?

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Well, I think that it’s not something that has been part of my research program but it’s certainly something that I experience in my study of reading development and the differences between children and how they acquire it, or adults, who can not read very well or adolescents, and the type of avoidance that they exhibit as a result of not being skilled enough to engage in this cognitive act. One can only speculate having learned to read myself with relative ease, but certainly my students who come up to me even at university and share the inordinate shame that they feel as adults in trying to hide it and stay up with their peers much less what children experience.

Anne Cunningham, Director, Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview: – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#ReadingExercisesIntelligence

Reading Shame can Generalize to Learning Shame

David Boulton: Yes. For many people I know, reading is the way that you quench your learning thirst.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: Yes.

David Boulton: And that if you can’t do that, there’s this collateral thing between reading and learning. It seems that if we become ashamed of our minds because of how poorly we read, then the aversion that you were talking about earlier doesn’t just stay restricted to reading. It more broadly encompasses all that’s on the other side of reading in terms of the cognitive exercise, in terms of the learning that can happen through print and through the vocabulary and the complexity of meanings that, as you say, really are not available in oral language.

Dr. Anne Cunningham: You’re right. It generalizes, it completely radiates out to other domains of inquiry. If in elementary school you find that you can’t read successfully, then there’s a body of research that shows that you apply it across other domains, that you think you’re not smart, that you think you’re not a good student. And because of those belief patterns you might choose other avenues. You might go to sports, you might go to art and those are all great places, but you at least want to have the opportunity, in ten years you don’t know what kind of person you’re going to be. You want to be able to have those opportunities that only print allows.

Anne Cunningham, Director, Joint Doctoral Program in Special Education with the Graduate School of Education at the University of California-Berkeley. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/cunningham.htm#DangerofReadingShame

Reading Shame

Pat Lindamood: We’ve had clinical experience with neurosurgeons and other physicians who are not reading and spelling accurately enough to really function well in their medical field.

David Boulton: That’s kind of scary.

Pat Lindamood: And it’s kind of scary… when you think about that.

David Boulton: Don’t tell me about the airline pilots, though. I don’t want to know.

Nanci Bell: One person that we worked with that was a doctor down the hall from us told me that he — the reason that doctors scribble prescriptions is because they can’t spell the word. Then on the other side, we were talking about the two-sided coin, then we have seen people trying to be physicians who cannot pass their boards. And they don’t have trouble reading and spelling words, they can’t comprehend. Their comprehension is like the second percentile. (see: shame stories)

Pat Lindamood and Nanci Bell, Founders, Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lindamoodbell.htm#ReadingShame