Shame and Self-Trust

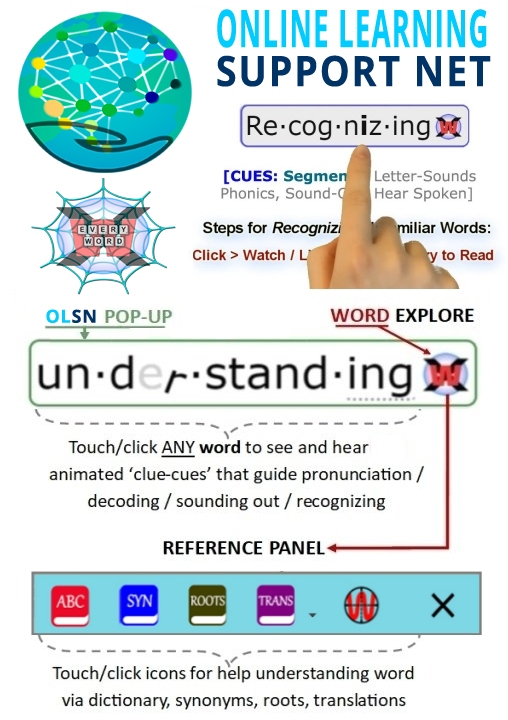

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Self-Trust

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: You know, Harold Bloom has a book called How to Read and Why. Harold Bloom is a Shakespearean scholar at Yale and he says, “The reason we read is to develop self-trust.” And developing self-trust takes years of deep reading. So, kids who don’t read don’t develop that self-trust because they can’t get access to the information. They can’t access to the ideation.

David Boulton: They don’t develop a self-trust in their ability to be abstractly self-reflective.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Absolutely.

David Boulton: They could have great potentials but they…

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: That’s right. They can’t compete at the idea level because they don’t have enough ideas that they can grab.

David Boulton: Or be able to engage in sufficient complexity of intellectually abstract processing.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Exactly.

David Boulton: That’s what I like about Stanovich and Cunningham, who brought forth what reading does for the mind.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Absolutely. That’s right.

David Boulton: This is a whole other lobe and dimension of virtual human extension that we need to survive in the world today and if we shame out on it we’re in big trouble.

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Absolutely. I mean, Jonathan Kozol says, “You don’t read, you don’t make choices.” How can you? It’s critical. And we can do this.

Check out the online HTML CheatSheet here and save the link because you might need it while composing content for a web page.

Interview

What Happens When You Can't Trust Your Brain?

Dr. Paula Tallal: What happens to you when you can’t trust your own brain to take care of this for you? What are the kind of defense mechanisms you might develop? Attention problems, impulsivity, acting out, being the class clown – anything is better in many ways for your self esteem and sense of well being than believing that you can’t trust yourself to even process the information in your world. That’s very scary. So, I think that you develop these other mechanisms.

David Boulton: This is shame avoidance.

Dr. Paula Tallal: It’s a shame avoidance to one self. It’s not only the external. I think we often think about the child who is developing behaviors to cope in terms of how other people are going to treat them, that’s certainly important. But I think ultimately it comes down to how you feel about yourself and can you trust yourself to get through the world, to keep you safe, to perform well, to make you feel good about yourself. And a lot of that has to do with automatic processing and automatic control of the information that’s coming into your world. I think a lot of children who are struggling with that will develop a lot of compensatory behaviors to try to gather a sense of being in control. Even if it makes them get in trouble, at least they were in control of getting in trouble. Whereas they cannot be in control of failure if they really can’t do it, and that feels a lot worse. That’s just a theory, it’s not scientific.

David Boulton: This where affect science comes in. It’s an important connection.

Dr. Paula Tallal: Yes. That’s why I’m saying some of this, and though this is not my scientific theory, it is my experience with doing psychotherapy with families and children. One of the things that has been so interesting is family therapy. When a family comes in primarily because they have a child who has a learning disability and you get started talking about the child what you often find is that there’s become so much focus on the learning disability for this child that the rest of the family, even the brothers and sisters, lose track of the other qualities of the child. If you go around the room and you ask everyone to say something positive or good about what each person is good at, for the other kids in the room in the family will say ‘He does this, he does that well’ or whatever. But when you get to the child with the learning disability they’re always trying to figure out something academically that that child is good at. ‘Well, that’s kind of tough, yeah, he can kind of do math pretty well.’ So this kid has just become the academic part of himself. So, you say well isn’t there anything else this child does well? ‘Oh I don’t know, he’s not really good at spelling and he’s terrible at reading.’ Well, what about other things this child may do well? ‘Well, kind of okay at geography…’ and you finally say…

David Boulton: This is the parent version of teach to the test though, isn’t it?

Dr. Paula Tallal: Yes, exactly. And then you finally say well does he have any friends? ‘Oh yeah, people just really like him, you know, he’s so nice and the neighbors say…’ Well, doesn’t that count? ‘Oh I thought you just meant about academics.’ They have gotten so focused because the school has gotten so focused and everything has become about this one area the kid is not good at, at the exclusion of all these other abilities this child does have. Many times the therapy is about rebalancing for the parents.

One of the things I often tell kids in private is, ‘You know what? When you grow up no one is ever going to test your reading again.’ And sometimes getting the parents involved in doing the testing has been really interesting because we do family genetic studies and test all the members in the family and just to see them remember what it was like to be tested. A lot of times they’ve forgotten how uncomfortable it is.

Interview