Dollars and Sense

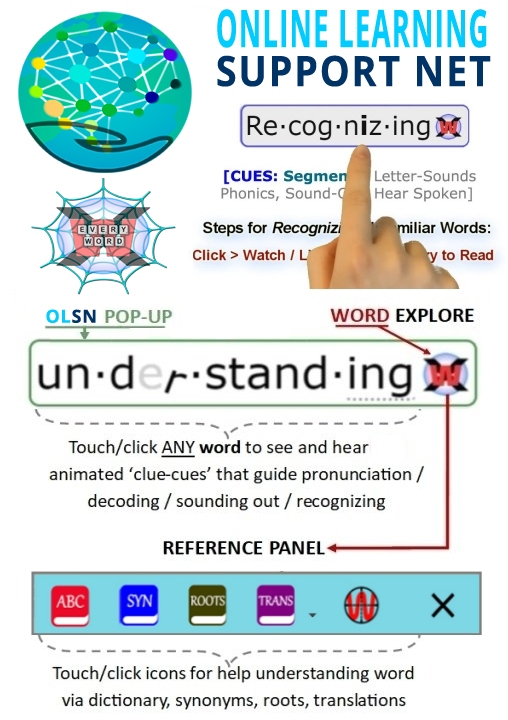

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Cost of Our Nation's Reading Difficulties - Hundreds of Billions of Dollars

David Boulton: Going on a broader, macro level – what does our population’s reading difficulties cost our nation? I’m not looking for precision, I’m looking for magnitudes of order. Economically, in terms of our global economic competition and in terms of the intelligence of our population and what that means about the security of our nation over the longer view.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: It is impossible to quantify the cost associated with reading failure or the advantages that flow to societies whose citizens are highly literate, who read well and read deeply and widely. It is clear, however, particularly in the context of a global economy, that increasingly the competitors of the United States, economic competitors, competitors in terms of ideas and philosophies, are competing in a way that undermines the ability of citizens in the United States to perform well based on the types of skills that involve lifting and pushing and using muscles. They are skills that depend increasingly on high levels of education. And even within high levels of education, the effects of global markets are that its only value added by special types of education, including high levels of literacy, that ultimately are going to allow us to compete well.

Software jobs that pay sixty dollars an hour in the United States are now done for six dollars an hour in India. For our citizens to compete, they have to bring to the software business a higher level of value. That value comes from the ability to conceptualize problems, to come up with novel solutions, to be creative, to think about how to market, speak to the world, speak to citizens of the United States, and all of those abilities flow from the understanding of a culture and oneself and other people that depends on reading.

David Boulton: So, as we said, reading is profoundly connected to this meta-linguistic verbal intelligence, and what makes us competitive is this innovative intelligence.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, absolutely. Innovative intelligence is a type of verbal intelligence. Verbal intelligence flows, depends on, and has a foundation in reading.

David Boulton: Back to being more specific on the economic implications. I’ve heard ninety million adults are not reading above the fifth grade level and are losing a couple hundred billion dollars a year in potential income, as it’s projected by literacy organizations, because they can’t read. I’ve heard there’s ten to fifteen billion dollars in research and federal spending and literacy program expenses. As you said before, it’s hard to get a handle on. But even in the roughest possible terms, what could we say the economic drag of this reading problem is in some kind of numbers?

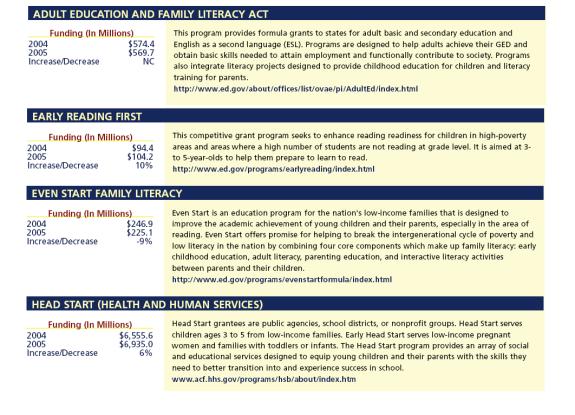

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Education, a substantial portion of the Department’s discretionary budget, which is roughly fifty-three billion dollars a year, is spent on problems that are related to reading.

Title I, which is our single largest grant program, which is a grant program for schools that serve children from low income backgrounds, is a grant program that is focused primarily on the problems of low academic achievement, and reading is at the core of academic achievement.

One could look into other areas of the department’s budget such as drop-out prevention or safe and drug-free schools, and find that these problems are correlated in the current circumstances in which there are large populations of kids who are not being served well by the schools, who are not doing well academically.

So, simply at the federal level, the cost of supporting academic achievement and reading is substantial. The federal budget is only about eight percentof the national expenditure on K-12 education. And so, if one imagines that simply in terms of elementary and secondary education, states and localities are spending in like kind for issues related to reading, then the cost just in terms of primary education becomes substantial.

What goes into law enforcement issues and jails, all the rest, under-employment, unemployment insurance, the need to support women and children who are not employed – all of these issues are connected to literacy and education. Presumably the cost for these programs would go down substantially in concert with increasing levels of literacy and education attainment.

David Boulton: So, just in terms of magnitudes of order, not even counting the lost opportunity cost dimensions of adults who are not reading well, we’re talking about hundreds of billions of dollars.

Dr. Grover (Russ) Whitehurst: Yes, absolutely. No question that the price tag is hundreds of billions of dollars; both to support the normal acquisition of reading and certainly to deal with the consequences of reading failure.

Grover (Russ) Whitehurst, Ex-Director (2002-08), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/whitehurst.htm#CostofReading

The Costs of Teaching Reading

David Boulton: Do you have any sense of what it costs us to teach our children to read?

James Wendorf: I don’t have a number for you. I don’t have a number.

David Boulton: Even a rough idea? A percentage?

James Wendorf: No. I can tell you that for those children who need remediation, if children do not have reading fluency by the end of third grade, it’s going to cost seven to eight times as much in time and in money to address their reading problems and get them up to grade level in reading.

David Boulton: Seven or eight times ‘x’, an unknown?

James Wendorf: Right. In other words, I don’t have that. In terms of dollars, every school district spends a different amount per child and that’s a statistic that is usually a very important one for school districts to trot out and either pride themselves on spending so little or pride themselves on spending so much, depending on where you live and what the property tax is like. But, I think it would be very difficult to come up with something like that for the country as a whole because there’s so much diversity.

David Boulton: There’s a lot of talk about the aggregate expense of reading difficulties from the 200 billion dollars in lost income opportunities to the adults that can’t read above a fifth grade level to the costs that literacy organizations, the federal government and so forth are spending to remediate reading. Do you have any number, any scope at all that you can comment on? Even a magnitude of order?

James Wendorf: Well, it’s billions. Billions lost.

James Wendorf, Executive Director, National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wendorf.htm#TheCostsofTeachingReading

Special Education Costs Twice as Much

The statistics on the negative sequalea of failing to read are horrifying. And we continue to think about this as a small problem. It’s not life threatening, that’s for sure, but it can be life destroying for a lot of individuals and we tend to forget that.

It’s remarkable that’s there’s no insurance coverage for most of the families who have children with these problems. There are very few physicians who are more than just aware of the problem. There are very few individuals who specialize in this problem. Many parents have said to me, ‘If I had a child with any other problem I would have some high level professional with a medical degree to take this child to to deal with the problem. But if my child has an educational problem I’m on my own with the teacher’ – who are very well meaning, but many times don’t really know what to do with the children who have a lot of difficulty in this area.

At the same time, we know remarkably well that if you know a child’s reading ability by the third grade you generally have a very good ability to predict whether they’re going to graduate from high school or not and what their abilities are going to be and what their future is going to be. That’s the reason we hear all children will read by the third grade, we know that’s highly predictive.

What are the rest of the statistics? I don’t know if you want to hear the horror statistics, but it’s quite remarkable. I had the opportunity to give a report to the Congressional Bio-Medical Research Caucus so I went into looking at the statistics. It’s something like every public major concern has a much higher incidence of reading problems attached to it from juvenile delinquency to teen pregnancy to failure to graduate from high school to drug problems. You take anything that we say is a major concern and there is a higher than expected incidence, by far, of individuals who have struggled with reading or have a frank learning disability.

It costs twice as much in real dollars to educate a child in special education than in regular education and yet through the history of maintaining statistics and all the additional money that has gone in we have seen a flat line in terms of the actual effectiveness of our current ability to remediate these issues. And yet we know that all these other problems are on the rise as we have more and more children who are having difficulty in learning to read. We do have a national crisis, well probably an international crisis, but we do have a major crisis in the United States.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#MostofOurChildrenAreLearningtoFel

Economic Consequences - Seventy Billion in Unnecessary Health Costs

Robert Wedgeworth: The American Medical Association has a major effort now to try to support health literacy among their patients because of the increasing costs to the health system for people who don’t understand the prescriptions that they’re given, they don’t understand how to take their medications. They don’t understand the diagnoses that are given to them by their doctors and the instructions that are attendant to those diagnoses. It’s estimated that we spend over seventy billion a year unnecessarily for people making special trips to the emergency room or extra trips to the doctor because they failed to understand the health issues that they have to deal with in their lives.

David Boulton: I read a report that that referred to data from the American Medical Association, a report without substantiation yet, that hypothesized that in addition to the seventy billion or so you just mentioned, a significant percentage of our nation’s annual health care costs are spent on low literate people who aren’t taking care of themselves in variety of ways that more literate people do.

Robert Wedgeworth: Yes. It’s really difficult to make accurate estimates of the cost of health literacy, other than being able to record the number of times people show up at an emergency room for special treatment because they don’t understand their medication, or other unnecessary visits to the doctor. Others are estimates that are really hard to pin down. But we know that these other instances do occur. It’s simply at this point it’s difficult to estimate them with any accuracy.

Robert Wedgeworth, Past-President, ProLiteracy Worldwide; Former Executive Director, American Library Association. Source: COTC Interview:http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/wedgeworth.htm#EconomicConsequences

Reading Failure Costs our Whole Society

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: It is interesting how politicized all the arguments get and how territorial people get on all of these things. I honestly believe that comes from knowing parts of it and not having the overall picture of it. I can’t imagine where else it would come from.

It’s one of these deals where we can quibble about all of these things. This is one where my notion is full speed ahead on all fronts. This isn’t a case of well, if you do that then we can do this. This is not that kind of a situation. We have a very big problem. These kids have a very big problem. Both on a societal level and an individual level and we’ve got to find a way to solve it. My kids can read at a very high level and they’re going to be living in society and trying to function with a bunch of folks that can’t do it and that’s going to lower the quality of their lives.

David Boulton: Yeah, they’re going to pay for it.

Dr. Timothy Shanahan: They’ll pay for it in terms of whatever economic costs there are for social programs, but they’re also going to pay for it in terms of political divides that exist. They pay for it in terms of lost opportunities that those low in literacy could have contributed. They lose in all kinds of ways. This is such a big problem. We really need to not be territorial about our solutions.

I’ve bet my career on the instructional solution. Not because I think the others don’t have value or can’t play out or might not work.

I just think we have to quit playing the games.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shanahan.htm#ThisisaSocietalProblem

Consequences of Reading Failure

David Boulton: We talked to Dr. Whitehurst, and from his perspective, it’s clearly hundreds of billions of dollars a year. We’re talking, when we aggregate this thing up, we’re on the other side of half a trillion dollars a year in costs associated, related in some way, to the psychological damage that’s happening in concert with instructional confusion.

Dr. Peter Leone: Right. Well, you’ve probably heard the analogies before the idea that if reading failure, for example, or early failure and the, as you say, associated shame, if that were a contagious disease, and if there was a vaccine for it, if we knew better ways of doing business, schools would say, “You can’t come in here until you’re vaccinated.” And schools do that. The public health movement in the 1950’s and 1960’s really helped schools kind of get on track, because there was this kind of concern about contagion and eradicating certain childhood diseases. But we don’t take school failure in the same sort of way.We have this “blame the victim” attitude. Maybe that’s not the best way to express it, but it’s a micro-level perspective.

David Boulton: Yes.

Dr. Peter Leone: As opposed to just taking a step back and saying, “What is it about those of us who are involved in teaching, organizing and managing schools that ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty, as you’re suggesting, as high as sixty percent of our kids aren’t as proficient as we’d like them to be.

David Boulton: Yes. And we know the first consequence of not being proficient at something so socially fundamental is self-blame and shame.

Dr. Peter Leone: Right.

David Boulton: And you can’t have chronic shame as the environment for complex cognitive learning.

Dr. Peter Leone: No, not at all. Not at all.

Peter Leone, Director, National Center on Education, Disability and Juvenile Justice; Professor of Special Education, University of Maryland. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/Leone.htm#ConsequencesofReadingFailure

Cost to the Nation is Incalculable

David Boulton: One of the things that becomes clear when you look at the afflictions that endanger children’s opportunities in school and life today, is that reading improficiency is on the top of the list.

Chris Doherty: Yes it is.

David Boulton: And according to our current data models, which are quite open to criticism, but even if you take them as rough ball parks, most of our children are not reading proficiently and, as a consequence, are in various degrees of serious psychological, intellectual, economic, and academic danger.

Chris Doherty: Yes.

David Boulton: In support of this, we’re putting together a table that shows the various things that children born today are at risk of in terms of what can cause them life harm as they develop. The reading challenge is putting more children at risk than everything else combined.

Chris Doherty: Yes, it’s as big a problem as there is.

David Boulton: Yes. And the cost to the nation, as Dr. Whitehurst and others have said, is hundreds of billions of dollars each year. It’s actually greater than the war on drugs, crime, and terror combined.

Chris Doherty: I don’t disagree. The only word that came to mind as you started your sentence was incalculable.

David Boulton: Yes. And for those that want to see it in economic terms, we’re talking about hundreds of billions of dollars in direct or related costs.

Chris Doherty: Absolutely.

Chris Doherty, Ex-Director, Reading First Program, U.S. Department of Education. Source: COTC Interview :http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/doherty.htm#AfflictionsThatEndangerChildren

We're All in this Together

David Boulton: Whether we’re concerned about the well being of the individual child, which, thankfully most of us are, or coming from another level which doesn’t seem so concerned with that, but is concerned with the cost of social pathologies. It doesn’t matter which side you come in, we end up in the same place here.

Dr. Peter Leone: Right. I think in creating, in essence, self-interest arguments, whether we’re concerned about the massive costs to all of us as taxpayers, or whether we’re concerned about kids that might look like our own children, or our nieces or nephews or our grandchildren, it doesn’t matter. The issue is that this is a really significant problem, and in helping people understand how it affects them, either as taxpayers, or as people who care about children, or as employers who want to hire people that are literate and capable, whatever the motivation is, we need to help people understand the self-interest argument in doing things differently for kids.

Peter Leone, Director, National Center on Education, Disability and Juvenile Justice; Professor of Special Education, University of Maryland. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/Leone.htm#AllinitTogether