Oral Language and Literacy

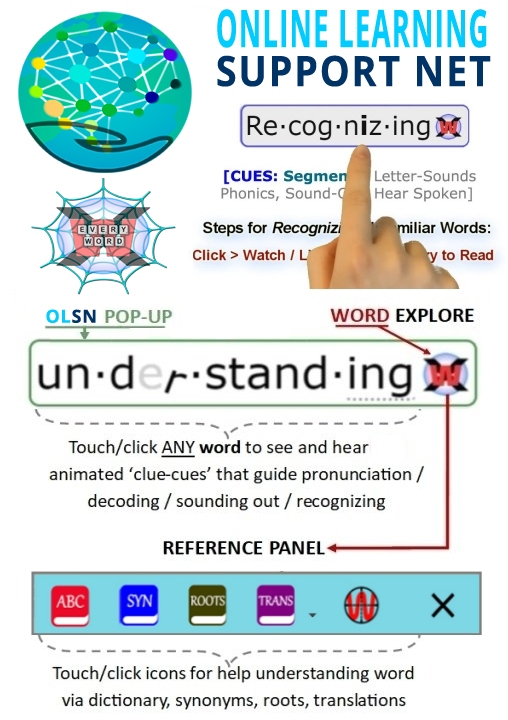

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Normal Nutritive Experience

Brains come in to the world, so to speak, expecting to be bombarded with language at an early age as part of their organizing principle, and human brains that don’t get that experience, in effect, are not getting the normal nutritive experience ….

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#AcquiringLanguage

The Detailed Age Trajectory of Oral Vocabulary Knowledge: Differences by Class and Race

Data from the Children of the NLSY79 (CNLSY) are pooled together across survey waves, 1986–2000, to provide an unusually large sample size, as well as two or more observations at different time points for many children, recorded at single months of age between 36 and 156 months. We fit a variety of multilevel growth models to these data. We find that by 36 months of age, large net social class and Black–White vocabulary knowledge gaps have already emerged. By 60 months of age, when kindergarten typically begins, the Black–White vocabulary gap approximates the level it maintains through to 13 years of age. Net social class differences are also large at 36 months. For whites, these cease widening thereafter. For Blacks, they widen until 60 months of age, and then cease widening. We view these vocabulary differences as achieved outcomes, and find that they are only very partially explained by measures of the mother’s vocabulary knowledge and home cognitive support. We conclude that stratification studies as well as program interventions should focus increased effort on caregiver behaviors that stimulate oral language development from birth through age three, when class and race gaps in vocabulary knowledge emerge and take on values close to their final forms.

Children are trained up to the family-specific pattern of language use, and it is variation in those family-specific patterns that largely determine the different vocabulary trajectories observed for children of different social classes.

George Farkas, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University and Kurt J. Beron, School of Social Sciences, University of Texas – Social Science Research 33,3 (September 2004) Source: http://www.nlsbibliography.org/qauthor.php3?xxx=BERON,+KURT

Shaping the Brains of Tomorrow

Newborns have an innate capacity to differentiate speech sounds that are used in all the world’s languages, even those they have never heard and which their parents cannot discriminate. But later in the first year they lose this ability as they become perceptually attuned to the language they will learn. By age 3, a child is forming simple sentences, mastering grammar, and experiencing a “vocabulary explosion” that will result, by age 6, in a lexicon of more than 10,000 words.

Ross A. Thompson, Developmental Psychologist, University of California, Davis – National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Source:http://www.duboislc.org/EducationWatch/ShapingBrainsOfTomorrow.html

Brain's Listening Dominated by Language

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Now in our case, in the human case, the listening experience of the brain is overwhelmingly dominated by language experience. It’s a powerful, language is an incredibly powerful, experential source in the average kid.

A Dutch scientist counted the words that his child had heard by the time he was nine months of age and he found the child has been in the presence of about four and a half million words, of which about half a million had been spoken to the child. The child had actually had half a million words directed to him, of which about fifty thousand were produced in highly exaggerated form, in parent-ese, where the parent is talking in baby talk to the baby so the child maybe can follow the speech a little more clearly. That’s before the child puts the meaning to the first word. That’s massive experential exposure.

Now you and I know families at which that same moment in time, a child may have not been in the presence, except maybe on the television, of fifty thousand words. Does that make a difference? Very probably. It very probably makes a difference and the more the parents are interacting with a child, in a sense, the more that the received speech means to the child, probably the greater value it has as a training signal. It will make a difference. Sound experience in a child will make a difference. The way the processor of the brain will be set up will be largely dominated to specialize for the native language the child is exposed to because that sound exposure is so massive and so special in the history of learning in the child.

David Boulton: It is so central to everything they’re listening for in order to pull themselves into their world.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Absolutely, and it becomes so quickly massively rewarding. I mean it has this wonderful aspect that it becomes a main source of reward for the child, moment by moment in time in life.

David Boulton: That ties in with the anthropological evidence that the evolution of the structures of our throat, jaw, tongue, and teeth have been selected to conform to the demands of articulating spoken language.

Dr. Michael Merzenich: Well, one of the things that happens, of course, is that it’s massively exercised. And because it is so massively exercised it’s also in every individual’s life history. It is incredibly refined and specialized for that specific purpose. You’re not just receiving. By the time you’re nine months of age you’re not talking very much, you’re mostly talking in the phonemic and syllabic kind of ways. But pretty soon you’re producing speech on a massive schedule and that also represents heavy motor exercise and sensory exercise for your face and pharynx and tongue and so forth.

Michael Merzenich, Chair of Otolaryngology at the Keck Center for Integrative Neurosciences at the University of California at San Francisco. He is a scientist and educator, and found of Scientific Learning Corporation and Posit Science Corporation. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/merzenich.htm#Brain’sListeningDominatedbyLanguage

Sources of Child Vocabulary Competence: A multivariate model

This study examines sources of individual variation in child vocabulary competence in the context of a multivariate developmental ecological model. Maternal sociodemographic characteristics, personological characteristics, and vocabulary, as well as child gender, social competence, and vocabulary competence were evaluated simultaneously in 126 children aged 1;8 and their mothers. Structural equation modelling supported several direct unique predictive relations: child gender (girls higher) and social competence as well as maternal attitudes toward parenting predicted child vocabulary competence, and mothers’ vocabulary predicted child vocabulary comprehension and two measures of mother-reported child vocabulary expression.

Bornstein MH, Haynes MO, Painter KM. Laboratory of Comparative Ethology, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-2030. Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9770912&dopt=Abstract

The Development of Symbol-Infused Joint Engagement

We found the developmental path of symbol-infused joint development began at 18 months when toddlers readily communicated with their mothers about immediate objects and events, rose rapidly over the next six months, then plateaued at 30 months, when symbols were routinely integrated into most interactions. This path varied depending on when a toddler began to speak.

Toddlers who were relatively early language users sustained symbol-infused engagement more often than their peers. In contrast, toddlers with very limited vocabularies at 18 months were less likely to sustain symbol-infused interactions, although they did gradually catch up to other children. Not surprisingly, we found that language skills at 18 months predicted language use at 30 months. More interestingly, we found that knowing how often toddlers sustain symbol-infused engagement from 18 to 30 months significantly increased our capacity to predict variations in latter language skills.

L.B. Adamson, R. Bakeman, and D.F. Deckner, Georgia State University. Source: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118748677/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

Longitudinal Relations Between 2-Year-Olds' Language & 4-Year-Olds' Theory of Mind

Individual differences in child language at 24 months and child verbal IQ at 48 months predicted unique variance in performance on the false-belief tasks at 48 months, although only the early language factor findings were statistically significant. These findings demonstrate previously unobserved relations between early language and later acquisition of complex concepts related to mind.

Anne C. Watson, Kathleen M. Painter, Marc H. Bornstein Journal of Cognition and Development, 2001, Vol. 2, No. 4: Pages 449-457. Source:http://www.leaonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327647JCD0204_5

Primary Oral Language

Dr. Edward Kame’enui: Now, in the context of failure, when kids fail in a symbolic system there are a lot of explanations, a lot of pieces we have to unpack. But that failure sets the stage for a fundamental ambiguity in terms of what is the primary cause for that failure. So, kids aren’t able to read. Kids come from Waimanalo, kids come from Kalihi. They come with their own language, and they come with their Pidgin, they come with their own variation of the Creole, and they say, you know, “Bombadda buggah goin o’erther.” What they are coming with is the language they know. It’s the only language they know. And for most of these kids that come to school, that language is sacred. They don’t know that their language is not represented in the print that they’re going to see in school.

Think about Hawaiian kids coming to school, they have this Pidgin, they start looking at the print, and yet the words they own, that they learned from their fathers, their mothers, their uncles, their aunts, their brothers and sisters, are not represented in the English print. So, right away you have a discrepancy between the languages they speak every day out in the neighborhood with their families that are simply not represented in the print that’s there. Right away you have a discrepancy here.

So, how do we understand that discrepancy? Is the problem the failure with the child? Not at all. The child knows that. The child knows that language. What it suggests is the system, then, has to appreciate that discrepancy, has to make an accommodation, has to make an adjustment. Well, with respect to the child’s language and that child’s inability to map his or her language, namely the Pidgin that he or she speaks every day, to the English and the alphabetic writing system. So, schools have to appreciate that.

Edward Kame’enui, Past-Commissioner for Special Education Research where he lead the National Center for Special Education Research

under the Institute of Education Sciences. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/kameenui.htm#PrimaryOralLanguage

Primary Oral Language Proficiency

Dr. Paula Tallal: If English is not their primary language, but it is the language they’re going to be asked to learn to read in, that creates a whole other layer in which we’re going to want to strengthen the oral language skills both at the phonological level, as well as at the grammatical and comprehension level in order to give a good solid base to learn to read and that’s a whole other issue.

David Boulton: Yes, it sure is. Without sufficient oral language proficiency in English teaching people to read it is a real challenge.

Dr. Paula Tallal: Yes, but you know we have public schools that are not in the business of teaching people how to talk. They’re in the business of teaching people how to read. One of our great social challenges is that there are many more children who are coming to school who really do need a direct approach to improving their oral language abilities and their communication abilities in order for them to become proficient readers. And we just don’t have that in most cases. We go right into reading. We do not sufficiently consider that many children have oral language weaknesses, because either the language they’re learning at school is not their native language or because they’re one of these many children who, for unknown reasons or for many different reasons, are just weak at oral language skills. Children with oral language weaknesses havebrains that are set up in such a way that is not as effective in the oral language domain. Those children are going to need more explicit help. Unfortunately they’re generally not getting it. They get to school and the first time anyone notices there is a problem is generally when they start to struggle with reading and therefore everyone just immediately assumes the problem is reading and they go right into reading remediation.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview –http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#ESL

Language Processing Underpinnings

“Where does that leave us? It leaves us with knowing a lot about the underpinnings of how the brain begins to process the sensory world, turn that into the phonological representations and turn those into syllables, words, phrases, and ultimately allow us to develop a written code which is the orthography or letters that go with those sounds. We know that when you have trouble anywhere along that route, you’re going to have difficulty with either oral language and/or written language.

“A lot of people out there might be saying now that ‘Well, I have a child who’s struggling a lot learning to read but they learned to talk perfectly.’ Well, they don’t always go together and that’s true. There are many, many children who have difficulty learning to read who didn’t have an overt oral language problem. And what I mean by overt is that there are lots of other routes to the same end. You can learn to talk relatively well without becoming that phonologically aware, without really needing to break the sounds down in your mind. It’s only when you hit reading that you must become aware that words are made up of smaller units. But it doesn’t mean that there really weren’t subtle language problems.

“One of the most remarkable scientific studies that has been published in my opinion recently was an epidemiological study funded by the National Institutes of Health that showed that if you just screened the oral language abilities of five year olds who are entering public school before you worry about their reading or anything like that, almost eight percent of them were so delayed in oral language development that they would frankly have been given a clinical diagnosis of having a language impairment. But in fact, very few of these children are tested because we allow a lot of individual differences in language development. When a child mispronounces words, it’s very common up to a certain age for everyone to think it’s kind of cute. For example, the child says ‘visketi’ when they meant spaghetti. Or ‘wabbit’ when they mean rabbit. Those are all normal healthy developmental trends up to a certain point in time. But we allow a lot of individual differences and we don’t really know on the whole very well when it is too late to be saying ‘visketi’ or ‘wabbit’ and when it is too late to not have your nouns and verbs go together properly.

“What was interesting about this study was that although almost eight percent of the children would have met the clinical diagnosis of specific language impairment, I think it was seventy-nine percent of those children had never been identified by anyone, their parents, teachers, pediatricians, anyone, as being at risk for a language or reading problem. They had the problem, but you know if you pointed out to a parent or something that the child really is delayed in language you would get responses like ‘Oh, I just thought he was shy’ or ‘No, he just doesn’t really pay attention very well’, or things along those lines.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#LanguageProcessingUnderpinnings

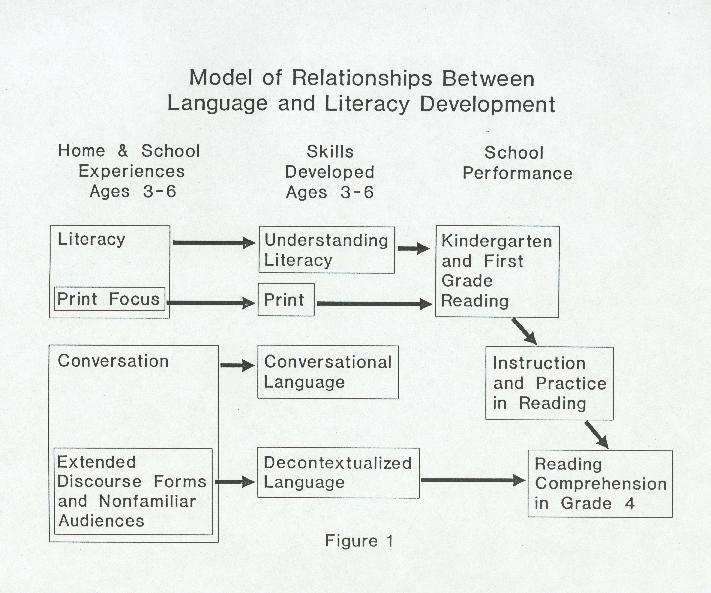

The Home-School Study of Language and Literacy Development

The Home-School Study of Language and Literacy Development is a longitudinal research project that has been on-going for the last thirteen years. The original purpose of the Home-School Study of Language and Literacy Development was to investigate the social prerequisites to literacy success, identifiable in both home and school interactions, of a group of racially diverse, English-speaking children from low-income families growing up in the Boston area. Source: http://www.gse.harvard.edu/~pild/homeschoolstudy.htm

Importance Of Preschool Era For Developing Skills Relevant To School

A primary focus of the earliest phase of the Home-School Study was on the home and preschool factors that would predict children’s language and literacy skills in kindergarten. In a series of analyses, we were able to predict the children’s scores on emergent literacy, vocabulary, and narrative production on the kindergarten SHELL (the School-Home Early Language and Literacy battery; see Snow et al. (1995)), from a variety of sources, including home interview information concerning home support for literacy, as well as some measures of decontextualized language and rare word use by mothers; classroom quality, extended talk, and vocabulary in preschool; and classroom quality in kindergarten. In combined regression analyses, science process talk, home support for literacy, and kindergarten classroom quality explain 35% of the variance in the scores on the narrative production task; home support for literacy and rare words in mealtimes and toy play explain 27% of the variance in emergent literacy; and home support for literacy, rare words at mealtimes and toy play, and kindergarten classroom quality explain 50% of the variance in the vocabulary measure (Dickinson, Snow, Roach., Smith, & Tabors, 1998).

The main conclusion from these analyses is that it is possible to find both home and school precursors for the children’s literacy and language skills when they were five years old.

Relationships Between Early And Later School Literacy Achievement

We continued to administer versions of the SHELL throughout the elementary school grades to track the children’s achievement in language and literacy (see Publications, Snow (1995)). Three particular tasks were repeatedly administered: the Wide Range Achievement Test – Reading (WRAT) (Jastak, & Wilkinson, 1984), the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) (Dunn, & Dunn, 1981), and a definitions task in which the students were asked to give definitions for ten common words. In 4th grade we administered the reading section of the California Achievement Test (CAT) (1992). Using growth modeling, we have found that student’s individual growth trajectories, both intercept and slope, on word recognition (WRAT) (r2=.66), vocabulary (PPVT) (r2=.50), and decontextualized language (definitions) (r2=.29) were all significant independent predictors of scores on the 4th grade reading comprehension test (CAT). In combination, word recognition intercept and slope, and vocabulary intercept explained 74% of the variance in the 4th grade reading measure. (Dickinson, Tabors, & Roach, 1996).

Source: http://www.gse.harvard.edu/~pild/Model.html

Co-Principal Investigator: Catherine E. Snow, Ph.D., Co-Principal Investigator: David K. Dickinson, Ed.D., Research Coordinator: Patton O. Tabors, Ed.D