Language and Reading

“…Because after all, written language must stand on the shoulder of oral language.” – Dr. Paula Tallal, Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#OralandWrittenLanguage

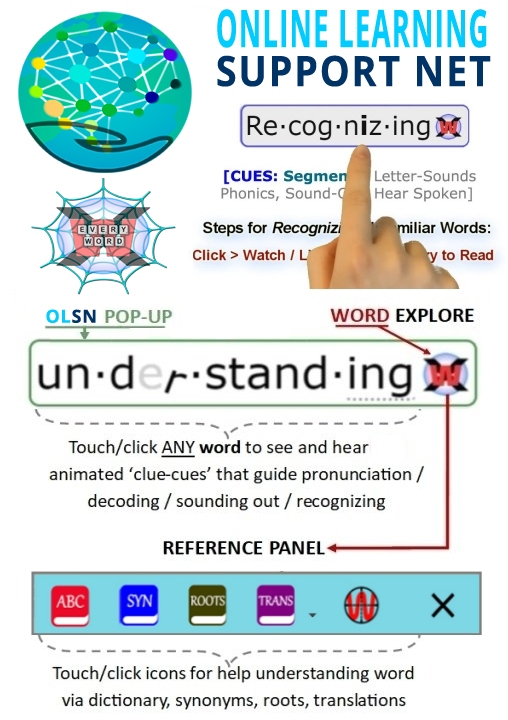

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Born to Learn: Language, Reading and the Brain of the Child

Our studies now show that the ability to distinguish speech sounds early predicts their later language and reading abilities. The better young children are at distinguishing the building blocks of speech, the better they are years later at reading and other more complex language skills.

Patricia Kuhl Co-Director Center for Mind, Brain, and Learning, William P. & Ruth Gerberding University Professor University of Washington. Source:http://www.ed.gov/teachers/how/early/earlylearnsummit02/kuhl.pdf

Oral and Written Language

When we look at a child learning to read we certainly see the visual side of it. When most people think about reading they think about the visual side of reading because it’s so obvious. There’s the squiggles on the page and that’s what you’re going to have to learn to put together. That’s the code, or at least that’s what people have thought for years was the code. But it turns out that that code has to be decoded in terms of the sounds that are made inside of words because those letters actually have to come to represent not the words, but the sounds inside of words.

Dr. Paula Tallal, Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#OralandWrittenLanguage

Indelible Connection

Early Reading and Scientifically-Based Research: Implications for Practice in Early Childhood Education Programs

There is an indelible connection between language development, vocabulary, and early reading.

National Association of State Title I Directors Conference – Melanie Kadlic & Mary Anne Lesiak Office of Student Achievement & School Accountability, U.S. Department of Education

Reciprocal and Robust Association

Emergent Literacy Intervention for Vulnerable Preschoolers: Relative effects of two approaches

There is a reciprocal and robust association between young children’s oral language proficiency and emergent literacy development Prediction studies have shown that an array of discrete oral language proficiency indices, including measures of vocabulary and grammar, consistently serve as moderate to robust predictors of conventional literacy outcome (for review, see Scarborough, 1998, 2000). Moreover, the prediction strength becomes increasingly powerful when several measures of language are combined into a composite index of language proficiency (Lonigan et al., 2000; Scarborough, 1998)

Justice, Laura M, Chow, Sy-Miin, Capellini, Cara, Flanigan, Kevin, Colton, Sarah; American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, Aug 2003

Correlation of Early Language Skills to Fourth Grade Reading Success

I think that language development has a much stronger functional role to play in reading development than maybe I ever recognized and maybe more than a lot of people recognized, not just me. What I’m saying is early language skills might not be very predictive for most kids of how well they’re going to do in first grade reading, but they’re actually pretty predictive of how well they’re going to do in fourth grade reading.

Timothy Shanahan, Past-President (2006) International Reading Association; Member, National Reading Panel; Chair, National Reading Panel; Professor and Director, University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy. Source: COTC Interview (unpublished phone interview):

Oral Discourse in the Preschool Years and Later Literacy Skills

This study investigated relationships between preschoolers’ oral discourse and their later skill at reading and writing. Thirty-two children participated in narrative and expository oral language tasks at age 5 years and reading comprehension and writing assessments at age 8 years. Children’s ability to mark the significance of narrated events through the use of evaluation at age 5 predicted reading comprehension skills at age 8. Children’s ability to represent informational content in expository talk at age 5 also predicted reading comprehension at age 8. Control of discourse macrostructures in both narrative and expository talk at age 5 was associated with written narrative skill at age 8. These findings point to a complex and differentiated role for oral language in supporting early literacy.

Terri M. Griffin, Manhattanville College – Lowry Hemphill, Wheelock College – Linda Camp, ReadBoston -Dennis Palmer Wolf, Brown University, First Language, Vol. 24, No. 2, 123-147 (2004) Source: http://fla.sagepub.com/cgi/content/short/24/2/123

Oral Language and Reading Success: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

We assess the importance of oral language by focusing on auditory processing, a variable strongly affected by the oral language of the family and peer group within which the youth is raised. This is the spoken language skills and habits that parents use in everyday conversation with their children, and that the children copy and absorb as they develop during the preschool age period, and on into the schooling years. The child’s resulting oral language – patterns of vocabulary, grammar, receptive linguistic understanding and expressive language use – are the principal resource that the child relies upon when she or he undertakes the first great task of formal schooling – learning to read.

Using a national sample of U.S. children aged five to seventeen, we have found that the child’s basic skill at auditory processing is a key mediating variable for the effect of class and race effects on reading achievement. This extends the work of Bernstein (1975) and Heath (1983), and suggests that oral language plays a central role in determining stratification outcomes. It is also consistent with a growing body of research demonstrating that children’s auditory processing (including phonemic awareness) skills are central to success at reading in elementary school (Adams 1990; Ehri 1996; Snow, Burns, and Griffin 1998).

We estimate a structural equation model in which this variable, along with other measures of basic cognitive skills, serve as mediators between race and mother’s schooling background and basic and advanced reading skill. The model fits very well, and the youth’s basic skill at auditory processing is both a major determinant of basic reading success, and by far the most important of the mediating variables. In particular, for children ages 5 to 10, this measure accounts for much of the race effect, and for more than half of the mother’s education effect on reading.

Kurt J. Beron, School of Social Sciences, University of Texas and George Farkas, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University Source: http://www.leaonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15328007SEM1101_8

Building Literacy Through Language in Preschool Classrooms

After children left kindergarten, we continued to assess their reading and language abilities throughout the elementary grades and into middle school and foundvery strong correlations between children’s skills in kindergarten and our end-of-seventh grade assessments. For example, seventh grade reading comprehension was strongly related to kindergarten receptive vocabulary (r = .71 ; p < .001). These data underscore the strong continuity between early and later literacy skills and highlight the need to identify experiences in the preschool years that contribute to the acquisition of the language and literacy skills.

David Dickinson, Professor, Boston College Source: http://www.cendi.org/interiores/encuentro2003/ponencia/p_dickinson.htm

Lower Verbal Ability from the Beginning

What we found was that the persistently poor readers seemed to have lower verbal ability from the beginning and to attend more disadvantaged schools than the group that had compensated.

Sally Shaywitz, Pediatric Neuroscience, Yale University, Author of Overcoming Dyslexia. Source: COTC Phone Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shaywitz.htm#Connecticut

Reading Disabilities: Why Do Some Children Have Difficulty Learning to Read?

Children who receive stimulating oral language and literacy experiences from birth onward appear to have an edge when it comes to vocabulary development, developing a general awareness of print and literacy concepts, understanding and the goals of reading. If young children are read to, they become exposed, in interesting and entertaining ways, to the sounds of our language. Oral language and literacy interactions open the doors to the concepts of rhyming and alliteration, and to word and language play that builds the foundation for phonemic awareness – the critical under-standing that the syllables and words that are spoken are made up of small segments of sound (phonemes). Vocabulary and oral comprehension abilities are facilitated substantially by rich oral language inter-actions with adults that might occur spontaneously in conversations and in shared picture book reading.

G. Reid Lyon, Past-Chief of the Child Development and Behavior Branch of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development,

National Institutes of Health, – The International Dyslexia Association’s Quarterly Periodical, Perspectives, Spring 2003, Volume 29

Annals of Dyslexia

Dyslexia is associated with a failure to establish a neural network-a set of connections among brain regions-in the language areas of the left hemisphere that provides support for the scaffolding of written language onto oral language.

Jack M. Fletcher, Ph.D, (2004) Professor of Pediatrics and Associate Director of the Center for Academic and Reading Skills at the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center. Source: http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3809/is_200412/ai_n9471600

Language Problems Revealed By Reading

A lot of people out there might be saying now that ‘Well, I have a child who’s struggling a lot learning to read but they learned to talk perfectly.’ Well, they don’t always go together and that’s true. There are many, many children who have difficulty learning to read who didn’t have an overt oral language problem. And what I mean by overt is that there are lots of other routes to the same end. You can learn to talk relatively well without becoming that phonologically aware, without really needing to break the sounds down in your mind. It’s only when you hit reading that you must become aware that words are made up of smaller units. But it doesn’t mean that there really weren’t subtle language problems.

One of the most remarkable scientific studies that has been published in my opinion recently was an epidemiological study funded by the National Institutes of Health that showed that if you just screened the oral language abilities of five year olds who are entering public school before you worry about their reading or anything like that, almost eight percent of them were so delayed in oral language development that they would frankly have been given a clinical diagnosis of having a language impairment. But in fact, very few of these children are tested because we allow a lot of individual differences in language development. When a child mispronounces words, it’s very common up to a certain age for everyone to think it’s kind of cute. For example, the child says ‘visketi’ when they meant spaghetti. Or ‘wabbit’ when they mean rabbit. Those are all normal healthy developmental trends up to a certain point in time. But we allow a lot of individual differences and we don’t really know on the whole very well when it is too late to be saying ‘visketi’ or ‘wabbit’ and when it is too late to not have your nouns and verbs go together properly.

What was interesting about this study was that although almost eight percent of the children would have met the clinical diagnosis of specific language impairment, I think it was seventy-nine percent of those children had never been identified by anyone, their parents, teachers, pediatricians, anyone, as being at risk for a language or reading problem. They had the problem, but you know if you pointed out to a parent or something that the child really is delayed in language you would get responses like ‘Oh, I just thought he was shy’ or ‘No, he just doesn’t really pay attention very well’, or things along those lines.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#LanguageProcessingUnderpinnings

Ripple Effects on Reading Difficulty

I do see some very interesting ripple effects when kids are not acquiring reading skills. For example, it might be that a particular child in fourth grade is having difficulty keeping pace with reading comprehension or with decoding, and because he’s having trouble with reading, he hates to read. And when he does read, he gets almost nothing out of it because he’s reading very passively. And because he’s reading very passively, he’s not able to use reading as a way of building his language abilities.

So, what oddly happens is that his language problems caused his reading problems, and his reading problems are now causing much more aggravated language problems. Those language problems, in turn, are going to make it hard for him to follow directions, communicate well with other people, and even use language inside his mind for something called ‘verbal mediation.’ Verbal mediation is the process through with which you regulate your behavior and feelings by talking to yourself. And believe it or not, a lot of kids with language problems really don’t use language as a way of regulating themselves.

They get in trouble, they get depressed, because they don’t have a voice inside that says, ‘Yeah, I could take that medicine. I could take that drug from that kid, and hey I’m a cool dude. But oh, if I take it, I could like wreck my brain, and I could get addicted and my mother will kill me if she finds out, and I could get arrested.’ And all of that comes out of language, that sort of verbal conscience that’s guiding you.

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless.

Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

Oral Language Weaknesses and ESL

Public schools are not in the business of teaching people how to talk. They’re in the business of teaching people how to read. One of our great social challenges is that there are many more children who are coming to school who really do need a direct approach to improving their oral language abilities and their communication abilities in order for them to become proficient readers. And we just don’t have that in most cases. We go right into reading. We do not sufficiently consider that many children have oral language weaknesses, because either the language they’re learning at school is not their native language or because they’re one of these many children who, for unknown reasons or for many different reasons, are just weak at oral language skills.

Children with oral language weaknesses have brains that are set up in such a way that is not as effective in the oral language domain. Those children are going to need more explicit help. Unfortunately they’re generally not getting it. They get to school and the first time anyone notices there is a problem is generally when they start to struggle with reading and therefore everyone just immediately assumes the problem is reading and they go right into reading remediation.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#ESL