Emotions, Language, and Literacy

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless. Dr. Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

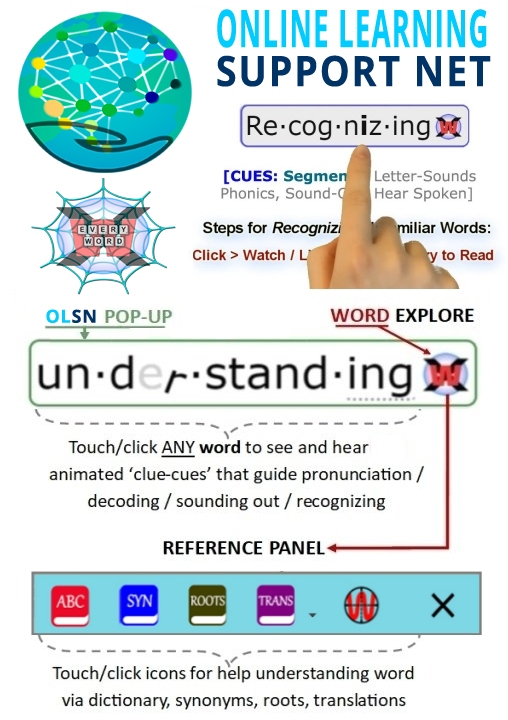

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Quality of Relationships with Important People - Where the Action Is

We have some amazingly compelling neuroscience that shows us how emotional experiences, the quality of the relationships the children have with the important people in their lives, that those relationships and the interactions that go with those relationships and the feelings that go with those relationships, actually influence the emerging architecture of the brain, they sculpt the wiring of the brain. There is no part of the brain, whether it be the way the brain thinks or the way the brain feels, there’s no part of it that isn’t influenced by these interactions and how the brain circuits are established. And that happens from the very beginning.

Obviously, there are very important cognitive kinds of underpinnings to reading. And there’s a significant amount of intellectual development and language development that’s necessary to master reading. But your ability to learn to read is also very much influenced by your feelings and your social development.

Now we know, we are learning, obviously have a lot more to learn — but we’re learning so much about how the wiring of the brain, how its architecture is very much shaped by experience and the environment. And what we learned is that the active ingredient in the environment that’s having an influence on development is the quality of the relationships that children have with the important people in their lives. That’s what it’s all about. That’s where the action is.

Jack P. Shonkoff, Professor of Child Health and Development and Director of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, Chair the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child Source: COTC Interview : http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/shonkoff.htm

Word Learning is Connected to Child's Emotional Life

Word learning is intimately connected to a child’semotional life, because infants learn language to talk about andthereby to share those things that they are thinking and feeling:the persons, objects, and events that make up the goals and situationsin everyday events that are the causes and circumstances of emotion.The principle of relevance is responsive, in particular, to achild’s emotional life and engagement in an interpersonal andphysical world.

Bloom L, Tinker E., Teachers College, Columbia University, USA Source: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/102/5/SE1/1272

Born to Learn: Language, Reading, and the Brain of the Child

Equally astounding, infants who were exposed to the same language material via DVD – either with audio and video or audio alone – showed no learning whatsoever.

Patricia Kuhl Co-Director Center for Mind, Brain, and Learning, William P. & Ruth Gerberding University Professor University of Washington. Source: http://www.ed.gov/teachers/how/early/earlylearnsummit02/kuhl.pdf

Facilitating Language Development

It is also well documented that television viewing does not enhance language development the way interactions with a nurturing caregiver do. The AAP Policy Statement on Media Education states “Parents should avoid television viewing for children under the age of 2 years. Research on early brain development shows that babies and toddlers have a critical need for direct interactions with and other significant caregivers (e.g., child care providers) for health brain growth and development of appropriate social, emotional, and cognitive skills.

Donna Rafanello, with contributions by Chet Johnson – Source: Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics

Accumulative Emotional Effect of Language

When we counted up the differences and did that kind of elaboration – how many affirmations an hour? The notion that by the age of four the children had heard about 750,000 times that were right and about 120,000 times that they were wrong. With very taciturn parents it was almost the reverse. They only were right about 120,000 times and had heard they were wrong about 250,000 times.

In other words, the massive life-time experience of affirmations and prohibitions indicating you’re right and you’re wrong is a life-time batting average that’s hard to overcome with just a little bit of positive experience.

Todd Risley, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at the University of Alaska. Co-Author “Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children.” Source: COTC Phone Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/risley.htm#LanguageEmotionalHealth (Note: The phone interview transcript does not match the video interview verbatim. The previous quote was taken from the video interview.)

Developmental Pathways and Intersections Among Domains of Development

As children start to develop language, they begin to form a history of the self (i.e., autobiographical memory). Parents and other caregivers help regulate children’s affective experience and assist in the development of a coherent life story and a cohesive self (Palombo, 1992). There is growing evidence that preschool children who have been exposed to significant and persistent negative experiences are at risk for constructing a lexicon of negative affect states related to the self (Nathanson, 1992) and are less adept at behavioral and affective regulation (Shields, Cicchetti & Ryan, 1994). They may develop rigid and controlling ways of interacting with others (Fischer et al., 1997). Adult caregivers influence children’s expressive systems by helping solidify links between their cognitive problem solving, emotions, and language use. Parents who talk about feelings and conflicts tend to have children who develop a better understanding of emotion (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990); those who encourage appropriate expression of negative emotions have children who tend to be more sympathetic and socially competent (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992).

Catherine C. Ayob, Harvard Graduate School of Education & Harvard Medical School and Kurt W. Fisher, Harvard Graduate School of Education Source: Developmental Pathways

Ripple Effects of Reading Difficulty

I do see some very interesting ripple effects when kids are not acquiring reading skills. For example, it might be that a particular child in fourth grade is having difficulty keeping pace with reading comprehension or with decoding, and because he’s having trouble with reading, he hates to read. And when he does read, he gets almost nothing out of it because he’s reading very passively. And because he’s reading very passively, he’s not able to use reading as a way of building his language abilities.

So, what oddly happens is that his language problems caused his reading problems, and his reading problems are now causing much more aggravated language problems. Those language problems, in turn, are going to make it hard for him to follow directions, communicate well with other people, and even use language inside his mind for something called ‘verbal mediation.’ Verbal mediation is the process through with which you regulate your behavior and feelings by talking to yourself. And believe it or not, a lot of kids with language problems really don’t use language as a way of regulating themselves.

They get in trouble, they get depressed, because they don’t have a voice inside that says, ‘Yeah, I could take that medicine. I could take that drug from that kid, and hey I’m a cool dude. But oh, if I take it, I could like wreck my brain, and I could get addicted and my mother will kill me if she finds out, and I could get arrested.’ And all of that comes out of language, that sort of verbal conscience that’s guiding you.

So, if you go all the way back to the language problem and say, yeah, it’s causing a reading problem, and the reading problem is causing the language problem, and the language problem is causing a behavior problem, and the fact that this kid can’t read, and other people around him can read much better is eroding his self-esteem, making him feel pretty worthless.

Mel Levine, Professor of Pediatrics; Co-founder, All Kinds of Minds Institute; Director, University of North Carolina Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning; Author, A Mind at a Time, The Myth of Laziness and Ready or Not, Here Life Comes. Source: COTC Interview: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/levine.htm#NegativeCollateralEffects

Shame Avoidance

In affect terms when a child or an adult feels that an incapacity is their fault, then this sense of being a defective person generalizes to other aspects of the personality. The idea that we’re defective or at fault because we can’t read then places us in a position where we want to avoid the bad feeling that comes when we can’t do it. And the more afraid we are of the awful feeling of humiliation that comes when we can’t do it, the more we avoid the educational process. It’s not just reading, it’s the idea of education.

Donald L. Nathanson. M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Jefferson Medical College, and founding Executive Director of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/nathanson.htm#effectoflearningtoread