Language

Clearly, it changes everything about what being a human being is. Again, I use the phrase, the symbolic species, quite literally, to argue that symbols have literally changed the kind of biological organism we are. Not just in evolution but in day-to-day life. I think we operate fundamentally different at a cognitive level because of this. – Dr. Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#VerbalSelf-ReflexiveVolitionalMemoryRecall

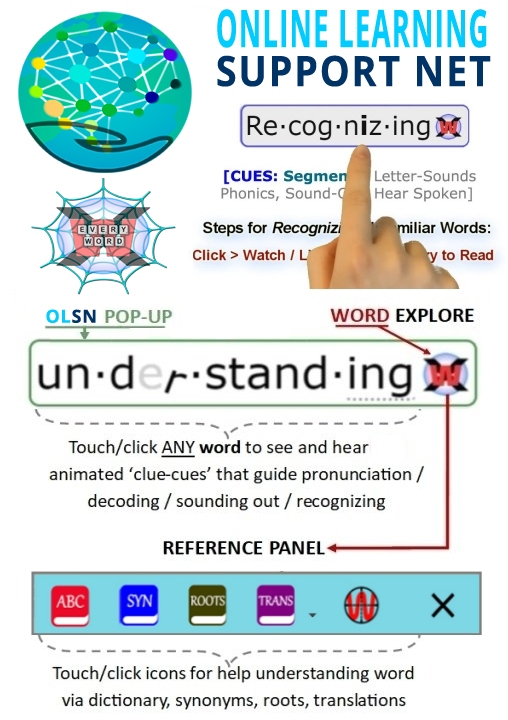

Note: Remember to click on any word on this page to experience the next evolutionary step in technology supported reading.

Language is What Makes Us Human

Dr. Paula Tallal: I mean language really does take us everywhere. If we think about what makes us human and makes us able to function differently, ultimately it is language; first of all language and of course subsequently written language. From the time we’re born our interaction with our parents, our interaction with peers, our interactions with our sense of self are very wrapped up with the language system.

Paula Tallal. Board of Governor’s Chair of Neuroscience and Co-Director of the Center for Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience at Rutgers University. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/tallal.htm#ReadingIlluminates

Single Most Distinguishing Attribute

David Boulton: So, from a human evolution point of view, you would agree … that the development of language is the single most distinguishing attribute of human beings today?

Dr. Terrence Deacon: I do think that the development of language is the single most distinguishing attribute. Now that doesn’t mean speech, necessarily. It means the support system that’s around language – the symbolic system. Of course our communication is much more than linguistic. Some of it is very old also. But a lot of culture is also linguistic-like in a variety of ways and clearly that has been around a long time.

The ritual, the mythology…simply ways of doing things that are organized conventionally, symbolically – this is a hallmark of our species. We have, in a sense, transformed and even reinterpreted much of our biology through this system. So much of what we do, whether it’s marriage, warfare, or whatever, has been transformed by this tool that has, in a sense, taken over and biased all of our interactions with the world.

David Boulton: I have long wondered what it must have been like to not be verbally self reflexive, to not be aware of myself in this mirror of words, this self-talk-story that’s going on. And yet it certainly seems that at some point human beings weren’t doing that at the level that we do it now, and, at some other point they were. That is a hugely significant threshold, regardless of where you place it in the evolutionary sequence.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#SingleMostDistinguishingAttribute

In the Beginning was the Word

David Boulton: Clearly becoming users of words was as or more important to us becoming what me mean by ‘human’ as walking erect. I mean, how could we even imagine the difference between human beings ‘before words’ and human beings ‘after words’? It’s almost biblical: ‘In the beginning was the word’.

Dr. John Searle: Alright, now this is the absolute point and we have to get this across: there are two great steps in the development of cognition. There’s the step where you go from being prelinguistic to being linguistic. Now, there are a lot of smart primates out there and a lot of smart mammals, but they can’t talk to each other in the way that humans can talk to each other. Even the bees with their celebrated bee language, it’s not much of a language. There’s not going to be much poetry, or even short stories in the bee language. I can guarantee it. They just don’t have the apparatus. But that’s step number one, you learn how to talk.

John Searle, Mills Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Language at University of California-Berkeley. 2004 National Humanities Medal for shaping modern thought about the nature of the human mind. Author of Mind: A Brief Introduction to the Fundamentals of Philosophy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/searle.htm#intheBeginning

Animal Communication

If language was just very complicated and you needed a really good brain with lots of learning devices to acquire it, then animals ought to have simple languages. But in fact, they have something very different than languages, a whole lot more like laughter and sobbing and smiles and frowns, which we also have. A simple language also wouldn’t require you to have a kind of crib sheet in your brain, a language device, a universal grammar that allowed you to say, ‘Oh, it’s one of those. I got that already’ because a simple language wouldn’t need all that support because you wouldn’t have to worry about it.

There wasn’t, in the standard explanations of intelligence, or of special language devices… any story that answered the reverse question – not why we have language, but why aren’t there simple languages out there? Why don’t animals just slightly less intelligent than us have just a slightly simpler language? And those less intelligent than them have a slightly simpler language than that? Or why aren’t there dozens of languages with different language devices, in different species, that are all like language but very, very different and not inter translatable? We don’t find something like that.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#Simple&ComplicatedLanguages

Human Language

Human languages have the capacity to represent in a way that animal signaling systems don’t have.

Animals can signal danger or sexual desire or a few things like that, but they cannot get this articulated form of precise representation that we get in human languages. So, the big jump off point is between animal signaling and human languages. Human languages have these remarkable capacities that they are compositional; that is, you can figure out the meaning of the utterance from the meanings of the parts and the way they’re composed.

Human languages have also involved this remarkable ability of commitment; humans commit themselves to doing something when they make a promise. They commit themselves to something being the case when they make a statement. There’s nothing like that in animal signaling. Now, that’s the basic of language: compositionality, representation and commitment. Keep those three in mind.

John Searle, Mills Professor of the Philosophy of Mind and Language at University of California-Berkeley. 2004 National Humanities Medal for shaping modern thought about the nature of the human mind. Author of Mind: A Brief Introduction to the Fundamentals of Philosophy. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/searle.htm#Humanlang

Abstraction and Differentiation

David Boulton: Was there an abstract sense of the ‘ not now’ before there was language to mediate it?

Dr. Terrence Deacon: I think there was not necessarily a sense of the ‘ not now’. The question is do you invent words to represent something you’re thinking, or do the words help you think things that you couldn’t have thought before you had them?

David Boulton: If you look at the optimal path for children learning words, and in my personal experience and observation, it’s at the very reaching edge of the differentiation or distinction that’s being made that the word can now act as a label.

Dr. Terrence Deacon: Right, and I think the acquisition of language as well as it’s early evolution has this same dynamic. Again, it’s a kind of a co-evolutionary dynamic in which the context is demanding it, in which the support is nearly there to produce it, in which the inside and the outside are both ready for a convergence on this result. The question about the origins of language really is what unusual social context becomes the support for creating a kind of communication that is a non sequitur in evolution that was not there before?

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#SenseoftheNotHereNow

How Old Is Language?

If language is new, if language is only a hundred thousand years old, or even less, a fifty or sixty thousand year old kind of process, then we should expect that it has had little effect on human brains – that whatever tweaks were used were, in a sense, clumsy kluges to make the thing work. We shouldn’t expect that it’s easy, that it’s fluid and runs without difficulty.

On the other hand, if language has been around for a good deal of our evolutionary past, say a few million years, or even a million years, that’s adequate time for it to have structured and reshaped the brain to be better “satisficed” to the problem of processing and using language in real time.

Similarly, language will have adapted. We will have adapted this language process to be better fit to our own constraints as we go along. The two will, in a sense, be in tandem, converging towards each other.

“The question one has to ask from the present time looking back is: Are we well adapted to this? Are we really a symbolic species or is this just a kluge added on top of a primate brain not well designed for this? I think the evidence for the age of this probably can be best picked out by comparing to something quite relevant to what we are discussing, and that is writing and reading.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#HowOldLanguageIs

Language as a Collective Phenomenon

Language is a case in which it doesn’t make sense for an individual to have a language. A unique individual language is a non sequitur, a non starter. It’s something that is systemic from the beginning. In the same sense, what we’ve learned about evolution and what we’ve learned about embryological development is they are also systemic. They’re not instructed from single genes that say you must be this shape. They’re the result of the genes setting in motion competitions, growth processes, interactions, communications, and out of those relationships emerge the structures that we see in embryos. Similarly, out of the relationships of ecosystems come the various niches and organism designs.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#LanguageasaCollectivePhenomenon

Language of Children

There’s another feature to this in which writing has adapted to some of the constraints of adults using it, of course, whereas speech and signing have probably adapted more to children acquiring it. The reason I say that is that the only languages that can be passed on down effectively and efficiently are those that can be picked up quickly and easily at the youngest possible age.

Why at the youngest possible age? Because if you have to use this for everything you do, to some extent you want to acquire it in a way that’s most suited to your brain, in which most of your resources have been organized with respect to it. Early on brains are quite plastic, quite flexible. The result is the more experience with language we have very early, the better we are at it as adults. Those who have been deprived in one way or another of that experience are quite poor in their linguistic abilities as adults, some never acquiring some of the features of language.

So to some extent, the very specialization that we have for acquiring language and acquiring it at an early age amplifies this difference in human brains. Thatbrains come in to the world, so to speak, expecting to be bombarded with language at an early age as part of its organizing principle, and that human brains that don’t get that experience, in effect, are not getting the normal nutritive experience of their expected evolutionary anticipation of this kind of environment that they’re about to fall into.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#AcquiringLanguage

Social Pressures Drives Communication

Well, of course there are many social insects that are in very large groups and they do have complicated communication. It’s typically one off communications, that is they have particular odors, particular sounds perhaps that they produce to organize themselves. Then, of course, instinctual responses when they encounter a movement, a sound, an odor from some other individual to produce their behavior. We get very complex social organizations. One might say, ‘Well don’t look at those creatures. They have very small brains.’ Of course they’re doing it differently. They’re more like little tiny computers solving this problem.

We do have animal groups, mammal groups and bird groups that can actually be in fairly large numbers interacting. For example, birds that have to nest in limiting areas, large herd animals that work together, large schools of fish that seem to coordinate their activities, and flocks of birds that control their activities in the numbers of a hundred. It’s not unusual to find large groups of social species carefully integrated in their interaction. For me, the size of the social group is not necessarily a telling feature. I think that there is a kind of minimal size of social group necessary to produce the kinds of pressures to generate language.

Terrence Deacon, Professor of Biological Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of California-Berkeley. Author of The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. Source: COTC Interview – http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/deacon.htm#SocialPressureDrivesLanguage